a friendship at Ravensbrück Part 4

A Return to the Land

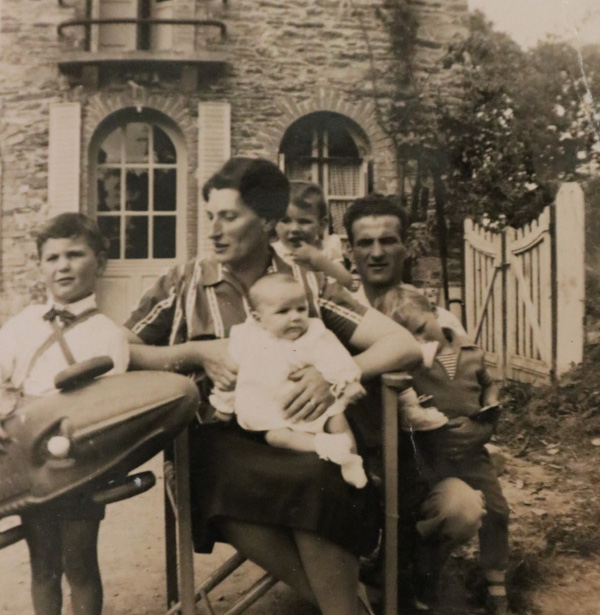

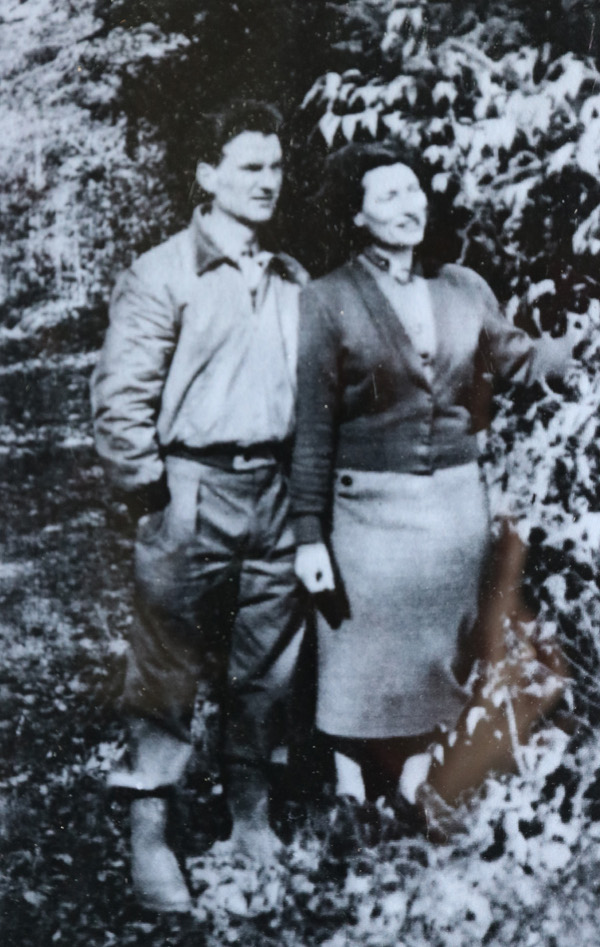

(Family archives)

In French

The planting of the orchards

After a month in hospital in Theresienstadt, Suzanne made the journey back to France alone. On June 22, she was evacuated by a French military ambulance to Speyer, Germany, where she was cared for at the Diaconesses Hospital. "I weighed 32 kilos when I was liberated. I spent two months unable to walk. If it had lasted one year longer, I would have been dead long ago," she said sharply. "Now I weigh 69 kilos, which proves that humanity is capable of bouncing back," she told the students with a smile.

Her convalescence period was long. Suzanne was not repatriated to France until July 14, the country’s national holiday. After a stop in Strasbourg, she arrived in Paris and finally reached her native Brittany five days later. There, she discovered that the Germans had burnt Sainte-Geneviève manor to the ground in retaliation for the battles with the Resistance at Saint-Marcel. Her family had lost everything. Suzanne was taken in by her aunt in the village of Guer, where she was joyfully reunited with Annic. After the evacuation of the Neubrandenburg camp, her cousin had survived the death marches and was liberated by the Red Army. Both had escaped hell but now struggled to find their place in the immediate post-war period. "When we returned, we had a very hard time because we felt like we were returning to an extraordinary and extravagant world. People had already been liberated for nearly a year and had resumed their normal lives. We thought we were dreaming,” Suzanne explained. The war might have been over and France was slowly recovering. But for both deportees, a part of themselves never came home from Germany. "In 1945, I realised, like Suzanne, that I wasn’t alive but trapped in my memories," Annic wrote in her memoirs.

“I felt as though I was returning like a dead person to a world I no longer belonged to.“

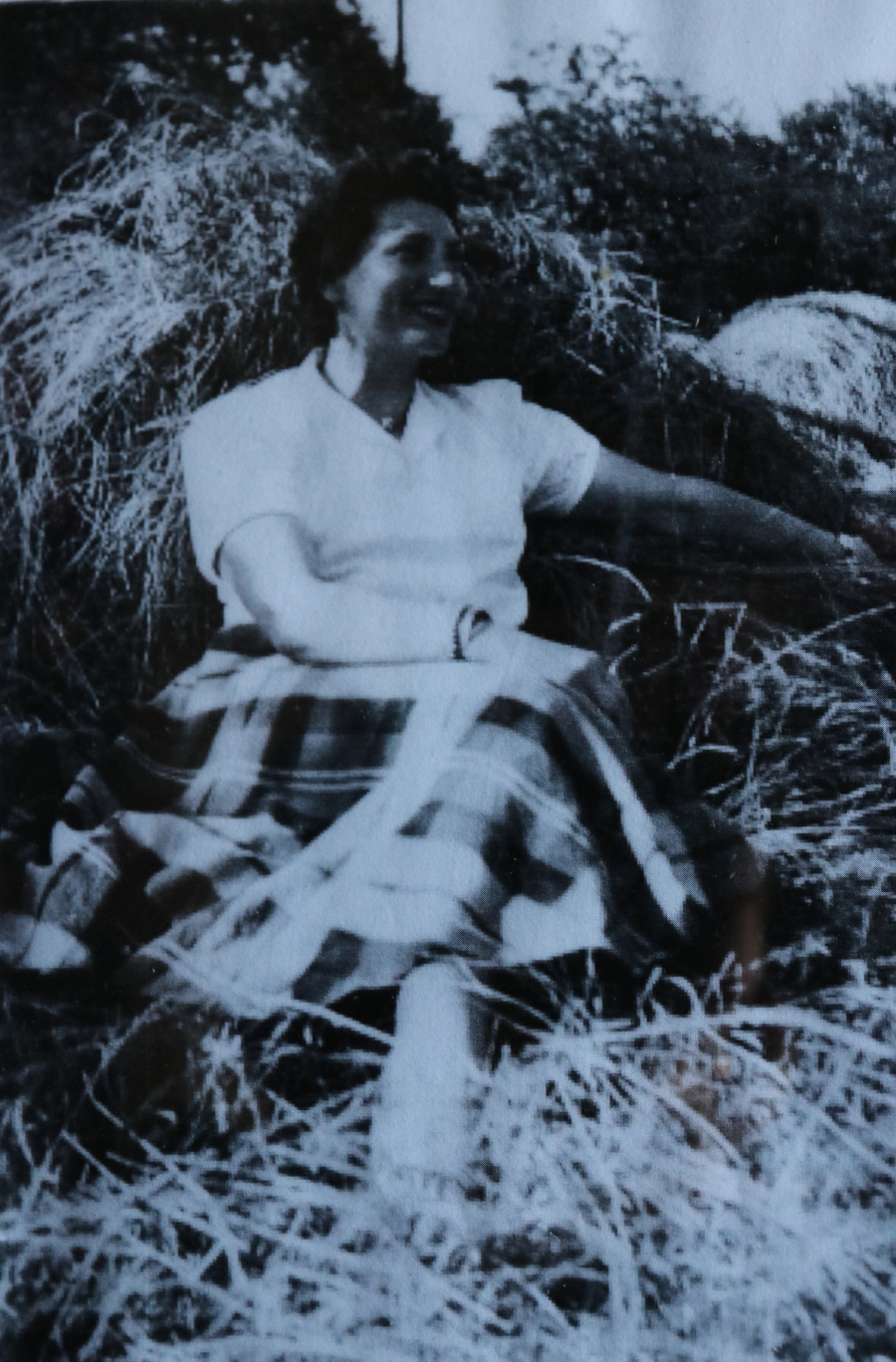

It was then that Daniel, Suzanne's fiancé, hoped to pick up where they had left off, having waited for his promised bride. But the wedding never took place. The former resistance member had not forgotten his attitude during the battle on June 18. At the age of 27, she returned to teaching and became the director of a domestic arts school in Ille-et-Vilaine. In Saint-Marcel, her mother, Geneviève Bouvard, fought to obtain war reparations because the manor had been destroyed by the Germans. The main property was never rebuilt, but its outbuildings were renovated. Around the same time, Suzanne inherited about 20 hectares of the Sainte-Geneviève estate and felt called to work closely with the land. In 1950, she left teaching, returned home, and decided to plant apple trees there. After enduring the ordeal of the camps, she now saw life very differently. "I had lost my house, but so be it; I had found my loved ones again. I returned home with the idea that in life, there are essential things and there are secondary things. I didn’t mind not having a home – as long as I could walk down a path without being beaten or arrested, as long as I always had some bread to eat and could find shelter when it rained." For Suzanne, "the main thing is life”.

To view this video, please accept YouTube cookies.

(Family archives).

Armed with nothing but her determination, Suzanne entered the farming world. As an unmarried woman, she stood out in an environment where men traditionally ran the farms. But she did not remain single for long. In 1955, she married Pierre Latapie, a former agricultural worker. Together, they developed their property, the Latapie Orchards, and became pioneers in organic farming. At the age of 39, Suzanne gave birth to her first son, Christophe. It was a triumph for the former deportee, who thought she would never have children. "I witnessed many moments of maternal joy in the ward, but never with such intensity and power," wrote a nun from the clinic who attended the birth. A year later, Olivier joined the Latapie family, followed by Jean-Michel in 1959 and Pierrick in 1961.

A pioneer

in organic farming

Suzanne Bouvard on her tractor in her orchards.

(Family archives)

Suzanne wanted to add to the joy of being a mother by becoming an accomplished farmer in a rapidly changing world. In the aftermath of the war, the countryside in Brittany was a hive of activity. Initiatives were set up to bring people in rural areas out of their isolation and old-fashioned ways. In the early 1960s, agricultural outreach groups (GVAs) were created to disseminate modern techniques to farmers, enabling them to increase yields and production, as well as improve accounting and management practices. From the outset, women's sections were also established, and Suzanne quickly became involved. She even became the first president of one such section in Morbihan. "We are almost the only ones in the department thinking about women's issues. What we don’t do will probably not be done by anyone," she said in an internal memo in 1964.

To view this video, please accept YouTube cookies.

In French

(Family archives).

Thanks to her experience with the orchards, Suzanne understood the unique challenges facing women farmers, who had to balance farm work with family life. The women's sections of the agricultural outreach groups encouraged them to participate in managing the farm alongside their husbands, to acquire new skills, and to challenge traditions to achieve better living conditions. For Suzanne, this went beyond the simple framework of farming. "Accepting responsibilities as a group leader, meeting with other women to discuss shared problems, speaking in public, taking notes, reflecting on their living conditions, their profession, and their children's future has contributed significantly to many women’s personal development," she wrote in a report in 1968. As the leader of this movement, strengthened by her experience as a resistance member and deportee, Suzanne played a major role in advancing the emancipation of women in rural areas.

Having become a prominent figure in Morbihan, she was made a Knight of the Order of Agricultural Merit in 1967, then an Officer in 1975. Active in her community, she was elected twice to the municipal council of Saint-Marcel. As someone who had experienced hunger herself, she was particularly committed to ensuring that children received better meals at school. Indeed her traumatic past was never far away. In 1984, she worked actively to establish the Museum of Resistance in Brittany, located on the very site of the Battle of June 18, 1944. During its inauguration, 40 years after her arrest, Suzanne, in keeping with her reserved nature, remained succinct in a report broadcast on FR3: "We made a 12-day journey in a cattle car across France to Romainville. And then followed the path all deportees know: Romainville – Saarbrücken – Ravensbrück."

Although Suzanne sometimes struggled to recount her time in the camps, her comrades were never far from her thoughts. She was notably a member of the National Association of Former Deportees and Internees of the Resistance (Adir), where survivors could find both material and moral support. For decades, Adir was presided over by Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, the niece of General de Gaulle, who had also been imprisoned in Ravensbrück. Suzanne welcomed her to Morbihan in 1992 to introduce her to the museum.

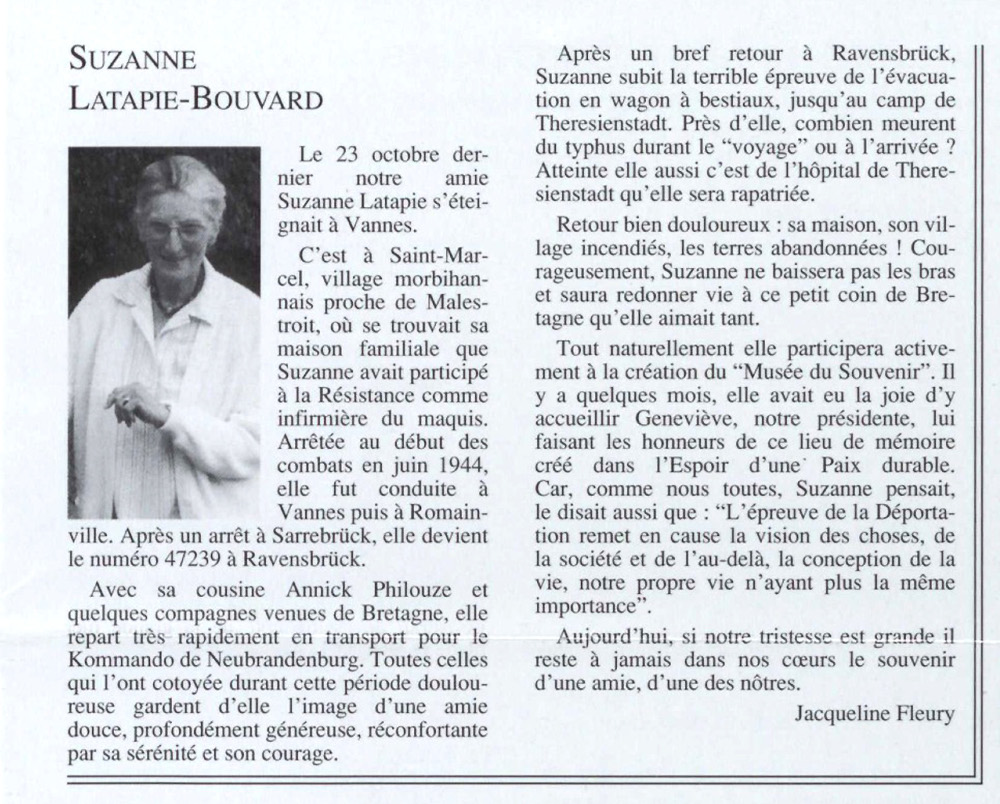

Adir’s tribute to Suzanne Latapie-Bouvard.

(Number 233 de Voix et Visages, La Contemporaine)

Adir’s tribute to Suzanne

Suzanne Latapie-Bouvard

Last October 23 our friend, Suzanne Latapie, passed away in Vannes.

Suzanne’s family home was in Saint-Marcel, a village in Morbihan near Malestroit, where she took part in the Resistance as a nurse for the Maquis. Arrested at the start of the battles of June 1944, she was taken to Vannes and then Romainville. After a stop at Sarrebrück, she became number 47239 at Ravensbrück.

With her cousin, Annic Philouze, and a few companions from Brittany, she was soon transported to the Kommando of Neubrandenburg. All those who met her during this painful period remembered her as a sweet friend who was deeply generous and who comforted many with her serenity and courage.

After a brief return to Ravensbrück, Suzanne went through the terrible experience of being evacuated by cattle car, to the camp of Theresienstadt. Many died from typhus around her during this “journey”, and also when they arrived. She was also suffering, and was eventually repatriated from hospital in Theresienstadt.

Her return to France was painful: her house and village had been burned and the land was abandoned. But Suzanne was brave – she did not give up and she knew how to bring life back to the little corner of Brittany that she loved so much.

She also participated actively in the creation of the “Musée du Souvenir”. A few months ago, she had the joy of welcoming Geneviève, our president, honoring her with a tour of this memorial site created in the hope of lasting peace. As Suzanne, like us all, felt and said: “The ordeal of deportation challenges one’s perspective on things, society, and beyond, as well as the very conception of life, with our own life no longer having the same importance.”

Today, though our sadness is immense, the memory of a friend, one of our own, will remain forever in our hearts.

Jacqueline Fleury

A few months later, the former resistance member from Saint-Marcel passed away after a stroke. Her comrades from Adir paid tribute to her in the association’s newsletter. Jacqueline Fleury, a former deportee from Ravensbrück, called her “a sweet friend who was deeply generous and who comforted many with her serenity and courage”. She reminded readers that, beyond death, the bonds forged in the camps were eternal:

“Today, though our sadness is immense, the memory of a friend, one of our own, will remain forever in our hearts.”