home together’ Suzanne and Simone,

a friendship at Ravensbrück Part 5

Preserving the Memory

Simone Séailles before the Second World War on holiday in Vendée.

(Family archives)

Remembering Simone’s sacrifice

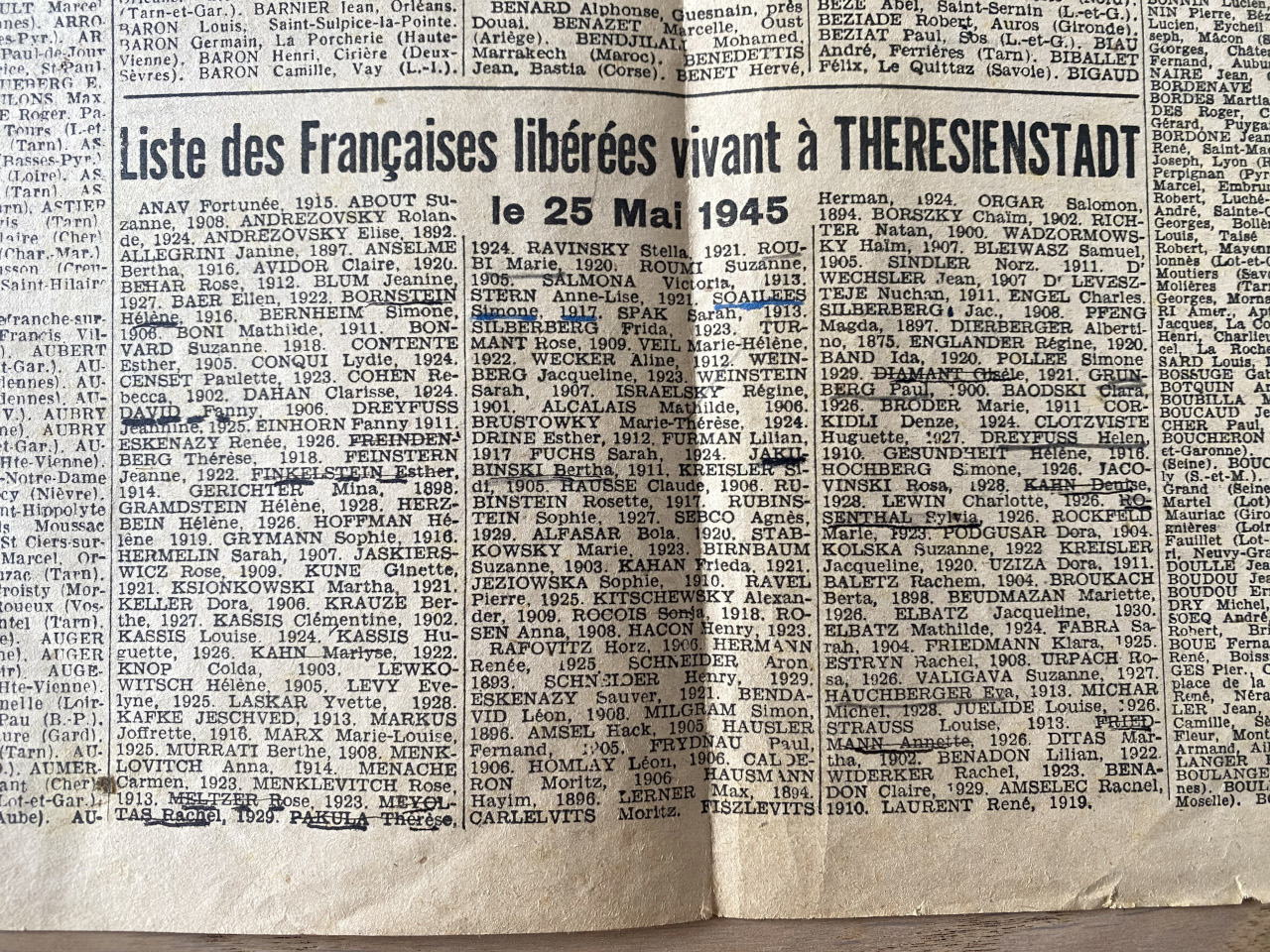

Unlike Suzanne, young Simone Séailles did not have the chance to pursue her passions or start a family. Her life ended on May 26, 1945, at Theresienstadt. But even more tragically, for several weeks Simone's family believed that she would return home to them in France. In an article published in the newspaper ‘Libres’, dedicated to prisoners of war and deportees, her name appeared on a list of people liberated in the Czechoslovakian fortress town on May 25, 1945, the day before her death. In a letter dated June 28, her mother Speranza Calo-Séailles expressed her impatience: "My Simone! We know that you are at Theresienstadt. We are waiting for you, you can imagine the joy we feel each time the doorbell rings (...) You have the kisses and tenderness of the whole family and all our blessings, my little darling. Your mummy."

Article from the newspaper ‘Libres’ in which the names of Suzanne and Simone appear, but with incorrect spellings of their surnames, “Bonvard” and “Soailees”. (Archives Danièle Lheureux)

It fell to Suzanne to break the terrible news to Simone’s mother. On July 2, while still hospitalised in Speyer in Germany, she wrote to Speranza: "Dear Madam, if I take the liberty of calling you 'dear' although I am a stranger to you, it is because Violette spoke to me so often about her mother that I feel that I know you, and I would like with all my soul to soften the pain that these lines will cause you." On a small sheet of paper in tiny handwriting, the Ravensbrück survivor retraced the journey of the two women during the death march, up to the death of her friend:

“I tremble, dear Madam, at the thought of the pain I have just caused you... I know that when faced with deep sorrow, only silence is appropriate.”

To her letter, Suzanne praised her friend’s exceptional character. "During the exodus, she was admirable in her courage, resourcefulness, and sisterly devotion to me, as my health at that time was particularly precarious. I will never forget that I owe her everything.”

To view this video, please accept YouTube cookies.

(Family archives).

(Family Archives)

Simone's parents then went to great lengths to recover her remains. In 1946, her ashes were repatriated to the crypt of the Cathedral of Saint-Louis at Les Invalides, in Paris. Séailles received the French Resistance Medal posthumously. Honours were finally paid to her on May 29, 1948, three years after her death, during a public funeral. Suzanne, along with Ariane Kohn, who had known Simone at the Fort de Romainville, formed the guard of honour around her coffin, which was covered with the tricolour flag. In the presence of her parents, her little sister and her two brothers, Jean and Pierre, who were awarded French Resistance Medals, her ashes were then buried in the cemetery in Antony, south of Paris, where the Séailles family lived. "Never has this town known such a funeral. The flowers formed a pyramid," reported the Franco-Greek newspaper ‘Indépendance’. Her parents commissioned two friends, the sculptors Jan and Joël Martel, who were very well-known at the time, to decorate her tomb. They immortalised her portrait in stone with an inscription reading, "Died for France".

Speranza Calo-Séailles did everything she could to ensure her daughter would not be forgotten, along with the other 1,500 women deported from France to Ravensbrück who did not return. She managed to contact several of her comrades from the Resistance and deportation period and asked them to write their memoirs. She gathered these texts in a moving work, "Simone and her companions" (Éditions de Minuit), published in 1947. Those who knew her, like Suzanne and Annic, praised her courage and generosity. "In their grief, your parents can find consolation in having had you as a daughter. If I have the happiness of having children one day, I will tell them about the magnificent life of my friend Violette," said Fanny Marette-Rey, a survivor of the Neubrandenburg Kommando. General de Gaulle even wrote a few lines: "May the example of Simone Séailles and her companions guide our homeland, saved thanks to them from dishonour and death, towards a future of peace and greatness." Memories of Simone also crossed borders. The Greek composer Manolis Kalomiris, who was close to her mother, composed a piece of music for her in 1948. In “La Mort de Vaillante" (The Death of the Valiant One), he paid tribute to "a life that was brief, but magnificent in selflessness, spirit of sacrifice, and heroism”. Keeping Suzanne's message alive

Simone Séailles’s tomb in the cemetery in Antony.

(Stéphanie Trouillard, FRANCE 24)

Keeping Suzanne's Message Alive

Photos of Suzanne at Sainte-Geneviève.

(Stéphanie Trouillard, FRANCE 24)

As the decades went by, memories of Simone gradually faded. In Antony, a small street bears her name, but the family home no longer exists. After Suzanne's death in 1992, the ties between the Séailles and Bouvard families weakened. Annic Philouze, the last witness to their friendship, passed away in 2017, just before her 100th birthday. Deeply affected by her experience in the camps, the woman who had found herself in the Maquis by chance devoted the rest of her life to God. Discreet by nature, she never sought recognition. Six years after her death, her town of Guer named a square after her. For her cousin Suzanne, the wait was even longer. While Saint-Marcel paid tribute to the Maquis fighters and Free France parachutists who fell in combat on June 18, 1944 and afterwards, only a small memorial stone mentioned Suzanne, despite her involvement in the community. In 2025, to mark the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the camps, the municipality finally corrected this oversight. The new building housing the school canteen and day care now bears the name of Suzanne Bouvard-Latapie.

To view this video, please accept YouTube cookies.

In French

Suzanne's memory lives on most strongly at Sainte-Geneviève, where her descendants continue to tend the orchards. On 32 hectares of the estate, they produce fifteen varieties of apples and raise some animals – all using organic farming methods and favouring short supply chains. Her daughter-in-law Irène, nicknamed "Mrs Apple”, is particularly committed to preserving the history of the place, her mother-in-law’s memory, and of the woman who saved her, her friend Simone. She organises gatherings that trace the journey of the Saint-Marcel Resistance fighter, a woman who drew on her Brittany roots to recover from such tremendous hardship. Irène wants to make her a symbol of resilience and to pass on her message.

Shortly before her death in 1992, Suzanne realised it was time to tell the younger generation about the horrors she had endured. As she spoke to these secondary school students from Morbihan, the former Ravensbrück prisoner opened up like never before. It is "too easy to draw a line under the past" and forget "those who risked their lives”, she said.

“The essential things in life are freedom, solidarity and respect for every human being.”

In keeping with her thoughtful nature, the cassette tape ends with concern for her young audience. "I hope I haven't tired you out too much?" she asks with a final burst of laughter.

A double rainbow over the Latapie orchards. (Stéphanie Trouillard, FRANCE 24)