home together’ Suzanne and Simone,

a friendship at Ravensbrück Part 3

A Friendship Forged in the Camps

Suzanne and Simone, an unbreakable bond

After the brutality of Ravensbrück, the two Breton women enjoyed some respite at Neubrandenburg. For more than a week, the new arrivals endured neither roll calls nor work. “This regime seemed almost idyllic,” noted Annic. They took advantage of this to get to know other prisoners, including a certain Violette, 27, “a lively, slender young woman with very expressive and warm black eyes”. Born in Paris, her real name was Simone Séailles and she had been arrested in January, 1944, as a liaison agent for the Sylvestre-Farmer Resistance network responsible for sabotage operations in northern France. A graduate of the École supérieure de physique et de chimie industrielles (ESPCI), Violette had adopted her disabled little sister's first name as her Resistance alias and made a strong impression on the two cousins. She lost none of her fire and commitment in the camps. “The incident that first brought Violette to my attention took place during this period; it concerned a discussion about factory work for which we would likely be employed and which some judged necessary,” recounted Suzanne in the book 'Simone and her companions' (Éditions de Minuit), published after the war in Simone’s honour. “I will always remember Violette's indignation, rebelling against this abuse of the rules of war and this violation of patriotic sentiment,” she added. But Simone – whom everyone called Violette – didn’t give a rap about the consequences and circulated a petition to protest against the work imposed on political prisoners. She even dared to confront the camp commandant, which earned her eight days without bread for having dared to disturb him – and the threat of being hanged if she rebelled again.

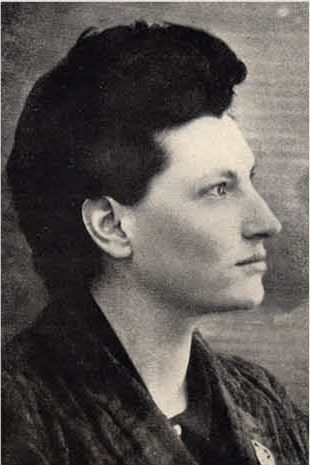

The Three Camp Companions: Suzanne Bouvard, Simone Séailles and Annic Philouze forged a string friendship in the camps.

(Family archives)

In French

Simone, however, remained undefiant and continued to display courage, particularly when it came to the well-being of her fellow detainees. “She was deeply concerned about our sick fellow prisoners,” recalled Suzanne. “Even though it was forbidden, she often entered the 'Revier' [barracks for sick prisoners, Editor's note] to visit them, passing them bread, even depriving herself of her milk ration for those suffering the most.” Over the weeks, the three women forged an unbreakable bond, particularly Simone and Suzanne. During her meeting with the schoolchildren, who hung on her every word as she told her story, she was keen to point out that:

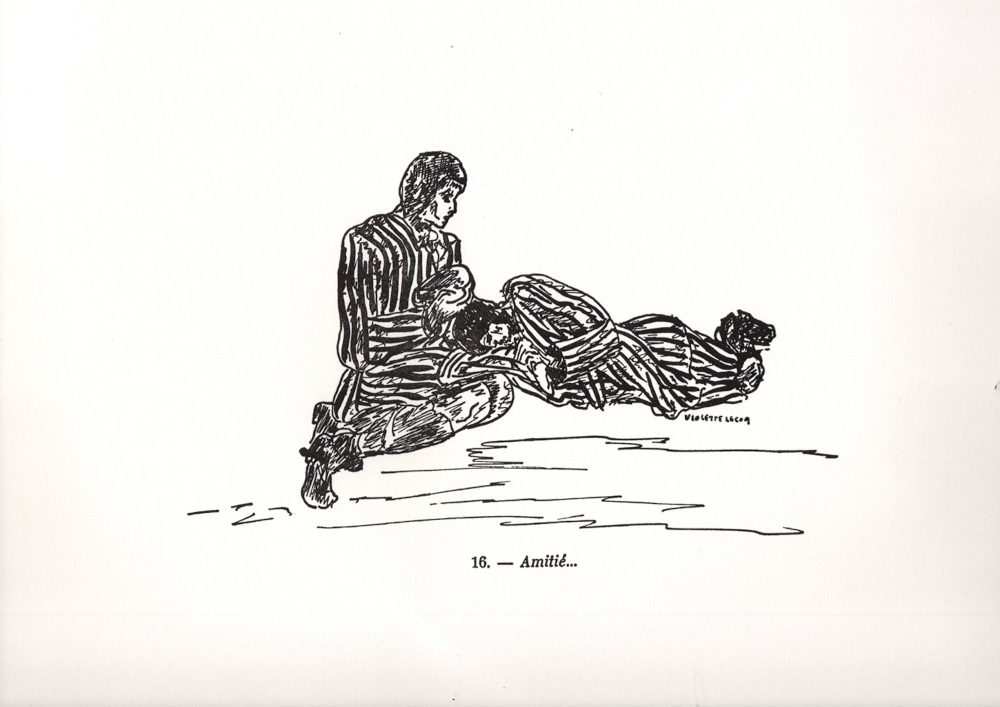

“I believe that what saved us from barbarity was friendship. We always tried to help each other. We wanted to prove to the Germans that we were still women and men. We had to remember that we were still human beings capable of friendship and devotion.”

Friendship in the camps, by Violette Rougier-Lecoq. ("Témoignages - 36 pen and ink drawings - Ravensbrück", Paris, Les Deux sirènes, 1948)

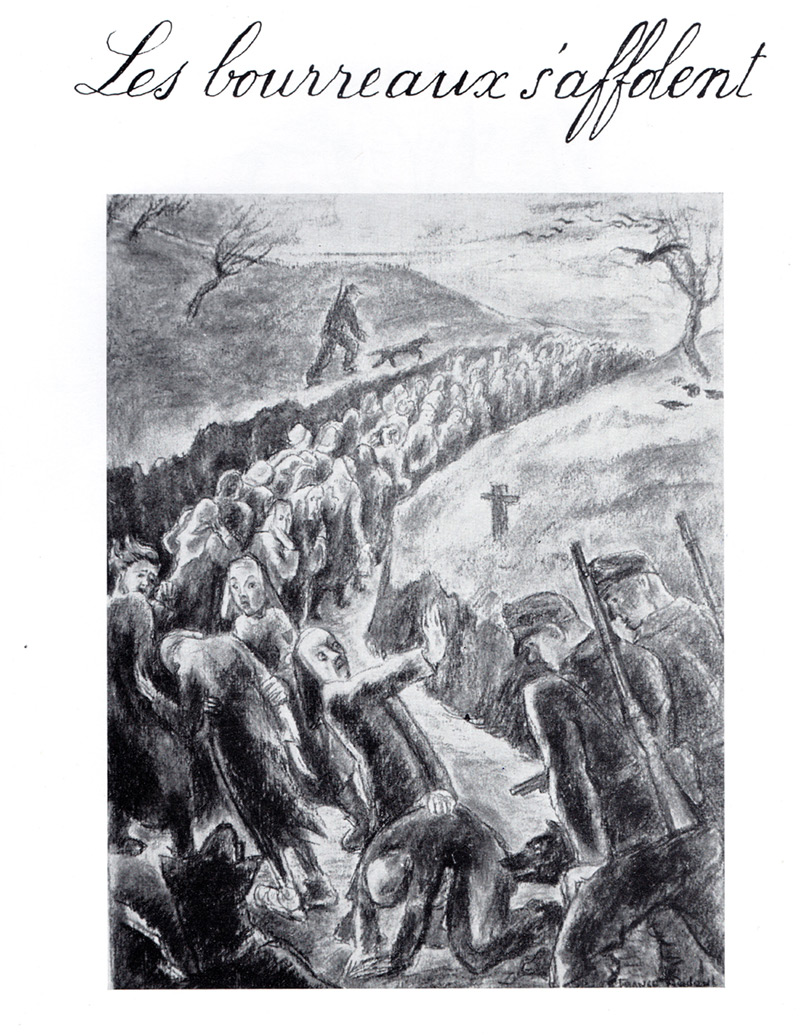

After a few days of respite upon their arrival at the camp, their living and working conditions gradually deteriorated. As at Ravensbrück, wake-up was around 3am and roll call took place from 4am to 6am. “When winter came, it was terrible. It was unbearably cold. Women would fall over in the snow and we weren't allowed to pick them up until the roll call was finished” Suzanne recalled. The work proved gruelling. In September, the cousins were assigned to clear an airfield hit by a British bombing raid and had to pick up thousands of small steel balls.

“When winter came, it was terrible. It was unbearably cold. Women would fall over in the snow and we weren't allowed to pick them up until the roll call was finished”

Suzanne recalled. The work proved gruelling. In September, the cousins were assigned to clear an airfield hit by a British bombing raid and had to pick up thousands of small steel balls. In October, they were put to work in a factory to replace the missing German workforce. The pace was exhausting: “It was really very difficult to work standing all the time. We would work one week during the day and one week at night. Our body clocks were completely disrupted and we could no longer sleep properly.” The deportees told each other stories about their lives before the camps to try and cheer each other. Suzanne talked about the Sainte-Geneviève manor and her daily life in Saint-Marcel, while Simone spoke of her mother's Greek origins as a singer and talked about her engineer father and her two brothers in the Resistance. At Christmas, even though they did not all share the same beliefs, they gave each other tokens of friendship – small objects made from factory materials or drawn from their meagre bread rations.

To view this video, please accept YouTube cookies.

At the beginning of 1945, as their strength diminished, the camp prisoners were met with a new ordeal. Faced with the advance of Allied troops, they had to dig anti-tank trenches in the middle of winter. The cold was biting, down to -20°C. “We would set out with the shovel and pickaxe on our shoulder and dig holes all day. It almost finished us off,” Suzanne commented soberly. In the spring, as rumours circulated about the arrival of the Americans or Soviets, there was fresh hope at the camp. But the hour of liberation had not yet struck. Suzanne learned that a convoy was to return to Ravensbrück, composed mainly of the weakest women. She was designated to leave on March 25, while Annic remained at Neubrandenburg. For the first time the cousins were separated. Suzanne was devastated, but consoled herself knowing that Simone would go with her. The two friends returned to their former camp, now overcrowded, for a brief stay. Forty-eight hours later, they were again thrown into a railway car.

A bouquet of flowers placed on the lake next to the Ravensbrück camp.

(Stéphanie Trouillard, FRANCE 24)

A cruel liberation

This new journey was even worse than the others: "We were so tightly packed in that we couldn't even sit together. We had to bend our legs and the nights were dreadful. If you moved, you bumped the person next to you," Suzanne recalled. She looked on helplessly while her comrade Rose-Marie Lafitte, from Toulouse, was dying: "She was extremely thirsty, and we had so little water ... she had developed very severe dysentery and her abscess, which could not be properly bandaged, caused her great suffering." On the eve of Easter, as the devout Suzanne whispered "final prayers" to her, Rose-Marie took her last breath. The next day, on April 1, the wagon doors finally opened. The survivors had just arrived in the Neu Rohlau camp, near Karlsbad (today Karlovy Vary, in the Czech Republic), in the northwest of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, a political entity established by the Third Reich.

For months, deportees from Ravensbrück had been brought there to work in a porcelain factory for the German army, then to manufacture weapons for the German air force. But in the spring of 1945, in the midst of the collapse of the Third Reich, production ceased. "We had no work and the freedom to act as we pleased outside roll calls," Suzanne recalled in the book in tribute to Simone. "The camp was clean and the 'Revier', run by a Russian female doctor prisoner, seemed like paradise compared to that of Neubrandenburg.” A few kilometres away, fierce fighting raged between the German army and the Red Army. As the cannons thundered in the distance, a small group, consisting of about fifty French women, sensed that the end was near. During this time, Suzanne went to the ‘Revier’ twice due to a high fever. And Simone was always by her side:

“I again experienced my friend's effective and truly sisterly concern of my friend.”

- June 19, 1944Arrested in Saint Marcel

- From June 19, 1944 to July 1, 1944Detained in Vannes prison

- From July 1 to July 12, 1944The long, long journey via the Compiègne camp and Paris

- From July 12, 1944 to July 18, 1944Interned at the Fort de Romainville

- From July 22 to July 26, 1944 Neue Bremm campTravelled to Sarrebruck

- From July 30, 1944 to August 15, 1944Quarantined at Ravensbruck

- From August 15, 1944 to March 25, 1945Forced labour at Neubandenburg

- From March 25 to March 27, 1945Returned to Ravensbruck

- From April 1 to April 20, 1945Evacuated to Kommando Neurohlau

- From May 5 to June 22Liberated at Theresienstadt camp

- Du 24 juin au 13 juillet 1945Evacuated to Spire

- July 13Repatriated to Paris

- July 19, 1945Returned to Brittany

Their friendship was sealed with a final ordeal. On April 22, an evacuation order rang out in the camp. Still feverish and barely able to stand, Suzanne had to leave Neu Rohlau and walk ten kilometres to the Karlsbad train station. Simone supported her with all her strength all along the route. On the journey, they found refuge in wagons on a siding. On the third day, Suzanne could go no further:

“Unable to continue, I stayed in the wagon, like those who were most exhausted, with the promise of being hospitalised nearby. It was at that moment that Violette, in an act of supreme devotion I will never forget, refused to leave so as not to abandon me.”

From then on, their fates were forever intertwined. Along with a handful of other French women, Suzanne and Simone were eventually forced to continue their journey. They were crammed into carts, standing for long hours as they were jolted along bumpy roads.

They were still riven by pangs of hunger. "Through chance encounters, Czech women, moved by pity, would give us raw potatoes that we devoured eagerly. Violette was admirable, fighting to ensure our survival with every last shred of her energy," said Suzanne.

“In the barns where we camped, her first concern was to get me settled as comfortably as possible, as the best of mothers would have done, before allowing herself to rest.”

Several of their comrades died on the road. On April 30, there were only five French women still alive when they boarded open freight wagons. Five days later, just when they seemed on the very brink of death, they finally arrived at Theresienstadt.

To view this video, please accept YouTube cookies.

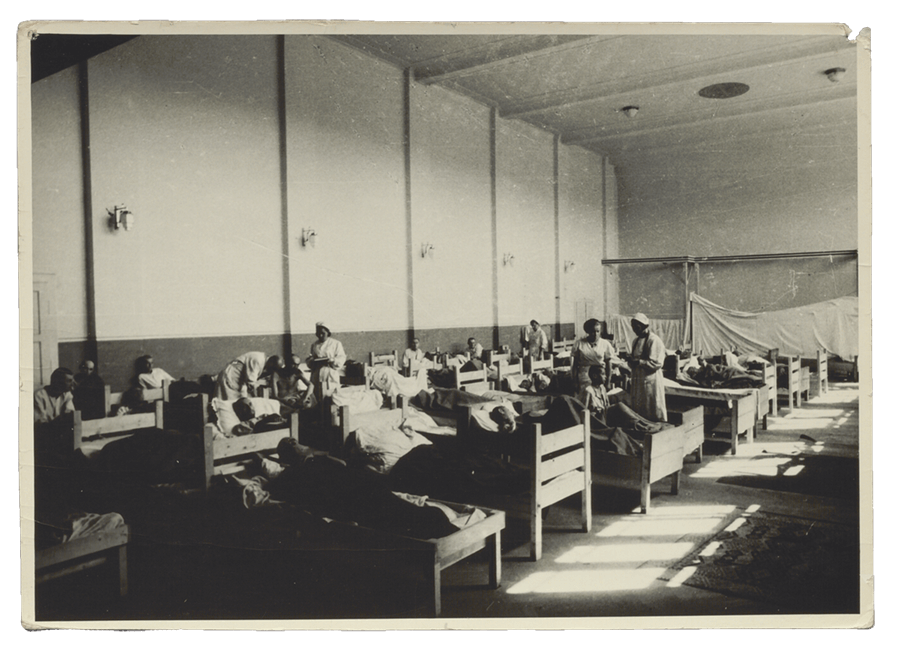

It was there that they were finally liberated, on May 5. After the Nazi guards fled, the Soviets prepared to enter this concentration camp, an old military fortress transformed by the German authorities into a Jewish ghetto. "Our only reaction was a silent gesture; we no longer even had the strength to show our emotions, so great was our degree of exhaustion," recounted Suzanne. The few survivors of the convoy were placed in a quarantine block. Suzanne noted Simone's state of extreme fatigue, but living conditions were still difficult. Each day, hundreds of people converged on Theresienstadt, including Jewish survivors and political prisoners. Like Suzanne and Simone, they had been taken out of the camps and forced on death marches. The fortress city was also struck by a terrible typhus epidemic. Left to their own devices for a week, the five French women could not receive any medical care.

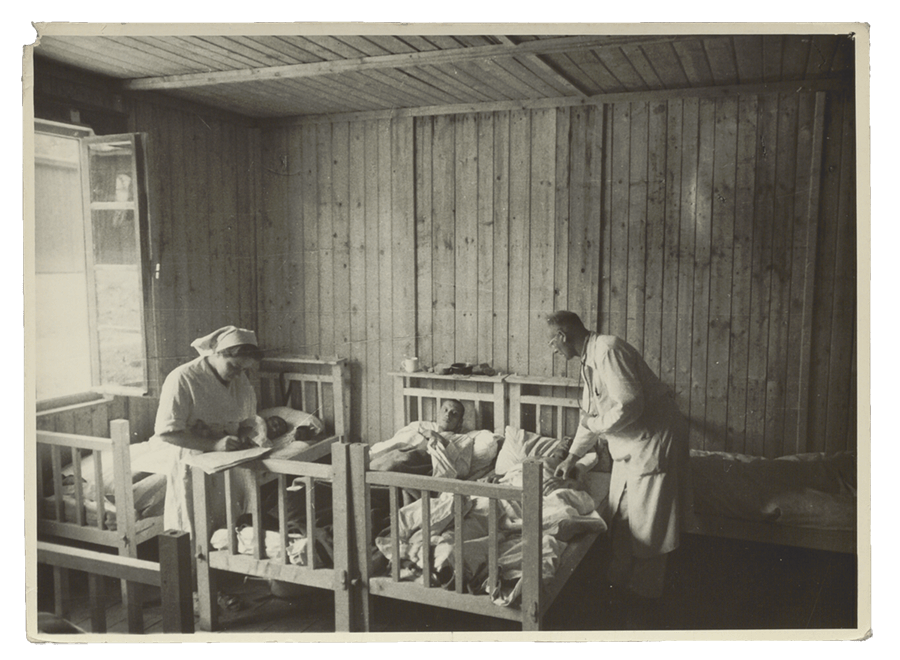

Health facilities after the liberation of the Theresienstadt Ghetto.

(Terezín Memorial)

In French

(Séailles family archives)

On May 12, they were finally transferred to another building. They began to think about returning to France. Suzanne felt a bit better, but Simone was experiencing breathing difficulties and suffering from dysentery. "I cared for her as best I could, trading bread and cigarettes for concentrated soup powder, which alone stimulated her appetite." Ten days later, Suzanne observed slight swelling on Simone's face and ankles and managed to get her hospitalised. But she suddenly found herself alone and desolate. Suzanne fell ill in turn, suffering from a very high fever. "I declared myself to be Violette's [Simone's] sister, I used my remaining strength to beg that I be transported to the same facility and the same ward as my friend," she said. Her wish was granted and the two women were reunited. But Suzanne saw that Simone's health had sharply deteriorated. Before going to sleep, they told each other: "We’ll make it home to France together."

On May 26, Suzanne awoke to a commotion in the small hospital room. “When I turned over, I saw, with indescribable astonishment, the body of my poor little sister being taken away ... her pain had ended. Her beautiful soul, without struggle, had escaped towards the light.” Barely had Violette regained her freedom when she passed away. Suzanne was inconsolable. Forty-six years after Simone’s death, her grief was palpable as she shared her story with the schoolchildren. She let her guard down to express her feelings about how her friend had given her life for her:

“For me, the most terrible thing was that she stayed by my side when I was very ill to help me. And in the end, she was the one who did not return. I asked myself, why me? Why not her?”