home together’ Suzanne and Simone,

a friendship at Ravensbrück Part 1

Immersion in the Resistance

In French

(Family archives).

A young lady from a good family

“What does it mean to be deported?” In a quiet voice, Suzanne Latapie, née Bouvard, addressed a class of high-school pupils in the northwestern Brittany region of Morbihan in 1991. “It means someone who has been taken by force from their country and put in another country,” she explained to the teenagers, who are taking part in the National Competition of Resistance and Deportation. She listed the different categories of deportees: those deported for racial reasons, for expressing dissenting opinions, and for acts of resistance. “They were people who would not allow themselves to be occupied by the Germans and who resisted in one way or another. They were part of a network or a Maquis,” she explained to the attentive class. The Maquis were rural guerrilla bands of French Resistance fighters known for hiding in remote areas.

Suzanne knew what she was talking about. When she was 25, she was deported to the Ravensbrück concentration camp, in Germany, for resisting against the Nazi-allied Vichy regime. In keeping with her thoughtful nature, she worried about the effect of her story on her young audience, almost apologising for it. “Is that it? Is that enough? Is it not too tiring? Are you sure you’re not bored?” she said with a burst of laughter to lighten the atmosphere.

At the age of 73, Suzanne opened up for one of the first times about her experience during the Second World War in a rare testimony, recorded at the time on cassette tape. For decades she had kept quiet about her traumatic past.

“We found it hard to talk about what had happened to us because people didn’t believe us. That’s why the deportations were sort of shrouded in obscurity, because it was too difficult to talk about it,”

she said regretfully. A year later, in October 1992, Suzanne passed away. This recording is the only one in which she recounts her experience of being deported.

Suzanne Latapie, right, during the 1980s.

(Press article).

Nothing predestined Suzanne to leave her village of Saint-Marcel in the Brittany region of Morbihan. She was born there, on September 27, 1918, on the Sainte-Geneviève estate, a manor house that had belonged to her family since the 1860s. Her father was a colonel in the French army and a town councillor. The Bouvards and their eight children lived a peaceful existence, actively participating in community life. From a young age, Suzanne taught catechism to the children at the village school.

In the spring of 1944, when France had already been occupied by Germany for four years, Suzanne, then 26, was teaching home economics. She was engaged to a man named Daniel, the wedding menus had been printed and her white dress was ready in her bedroom at the manor. But in early June, her destiny took a dramatic turn. Until then she had been relatively spared by the war, but she was suddenly plunged into the conflict when, in just a few days, the village of Saint-Marcel became an epicentre of the Resistance in Brittany.

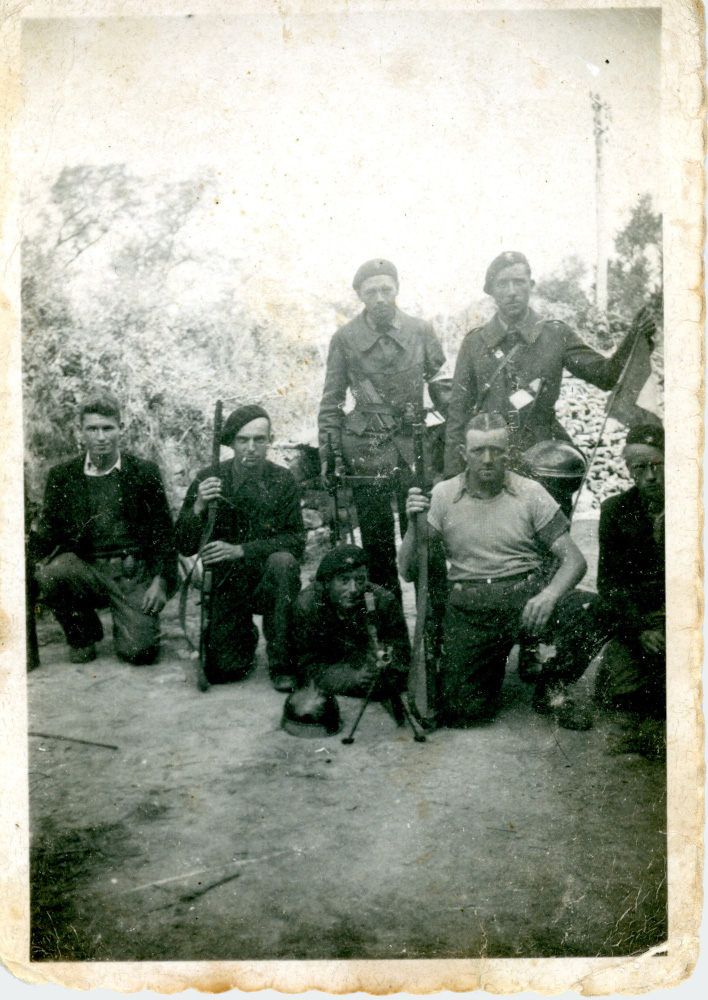

The battle of Saint-Marcel

During the night of June 5-6, 1944, a combat group from the 2nd Parachute Chasseur Regiment was parachuted into this small corner of the Morbihan countryside. These France libre (Free France) soldiers, who had come from London, belonged to an elite unit under British command: the Special Air Service (SAS). Their mission was to carry out sabotage operations to slow the progression of German troops towards Normandy, where the D-Day Landings had just taken place. Local Resistance fighters quickly led them to the Nouette farm, near the village of Saint-Marcel. This location, which had already been serving for several months as a secret parachute drop zone, was chosen as a rallying point for the FFI (French Forces of the Interior) in Morbihan.

In the following days, the Saint-Marcel Maquis was formed. More than 2,000 FFI, supervised by 200 SAS, passed through the camp. Suzanne witnessed this flurry of activity from the Sainte-Geneviève manor. From June 7 onwards, her family hosted the first wounded from the Maquis. Trained in nursing by the Red Cross, Suzanne did not hesitate to come to their aid. “They were clumsy because they had never held a rifle before and very often, there were accidents. I took care of a young man who had been shot in the foot when his friend misfired,” she told schoolchildren in 1991. Very quickly, the Bouvard residence became part of the Maquis camp: “There was constant coming and going. Our house was right in the thick of it. I had the opportunity to be of service to the Resistance, as everyone did. It wasn't particularly heroic.” A few days later, however, she had to deal with a much more serious case. On the manor’s kitchen table, she treated a parachutist who had been shot in the lung and managed to save him.

On the morning of June 18, she welcomed her cousin Annic Philouze, who had come from Rennes to visit her brother, who was recovering in a nearby clinic after being wounded in a bombing raid. It was then that gunfire erupted near the manor. After a German patrol invaded into the Saint-Marcel camp, violent clashes pitted the parachutists and Resistance fighters against the occupation forces throughout the day. A first aid post was set up at Sainte-Geneviève, but the situation became increasingly dangerous. “The Germans thought that our house was the headquarters,” Suzanne recalled. “We were bombarded from all sides with relentless machine gun fire. Bullets were coming through the windows.” she said. In her unpublished memoirs, preserved by her family, Annic provided more details. She notably mentioned that her cousin's fiancé was present but proved to be of little help. Paralysed by fear, Daniel took refuge behind an armchair. “Without meaning it, his panic became contagious,” Annic remembered. Despite the risks, Suzanne decided to take matters into her own hands. Accompanied by her cousin and other family members, she left the property to head towards the nearby town of Malestroit to escape the fighting. Along the way, her fiancé ran off to hide in a farm.

To view this video, please accept YouTube cookies.

In French

The following day, at dawn, while the Resistance fighters had dispersed into the countryside, she decided to return to the manor with Annic. She hoped to find her mother, from whom she had no news, and to retrieve some belongings. But when they turned a corner on the road, they ran straight into the German troops. The soldiers had just searched the manor, where they found British bandages. The two young women claimed they were just going to milk the cows but the soldiers weren’t taken in. With a vigorous 'raus!' (move out!), they arrested them. The Wehrmacht soldiers even forced them to help carry the body of a German killed during the battle to the village of Saint-Marcel. A few hours after the fighting, the village was no longer the same: it was now occupied by several hundred German soldiers. Suzanne felt certain they were about to be killed.

“They stood us up against a wall and truly then, I believed we were going to be shot.”

In the early afternoon, the cousins were finally pushed into a truck and driven to Nazareth Prison in Vannes.

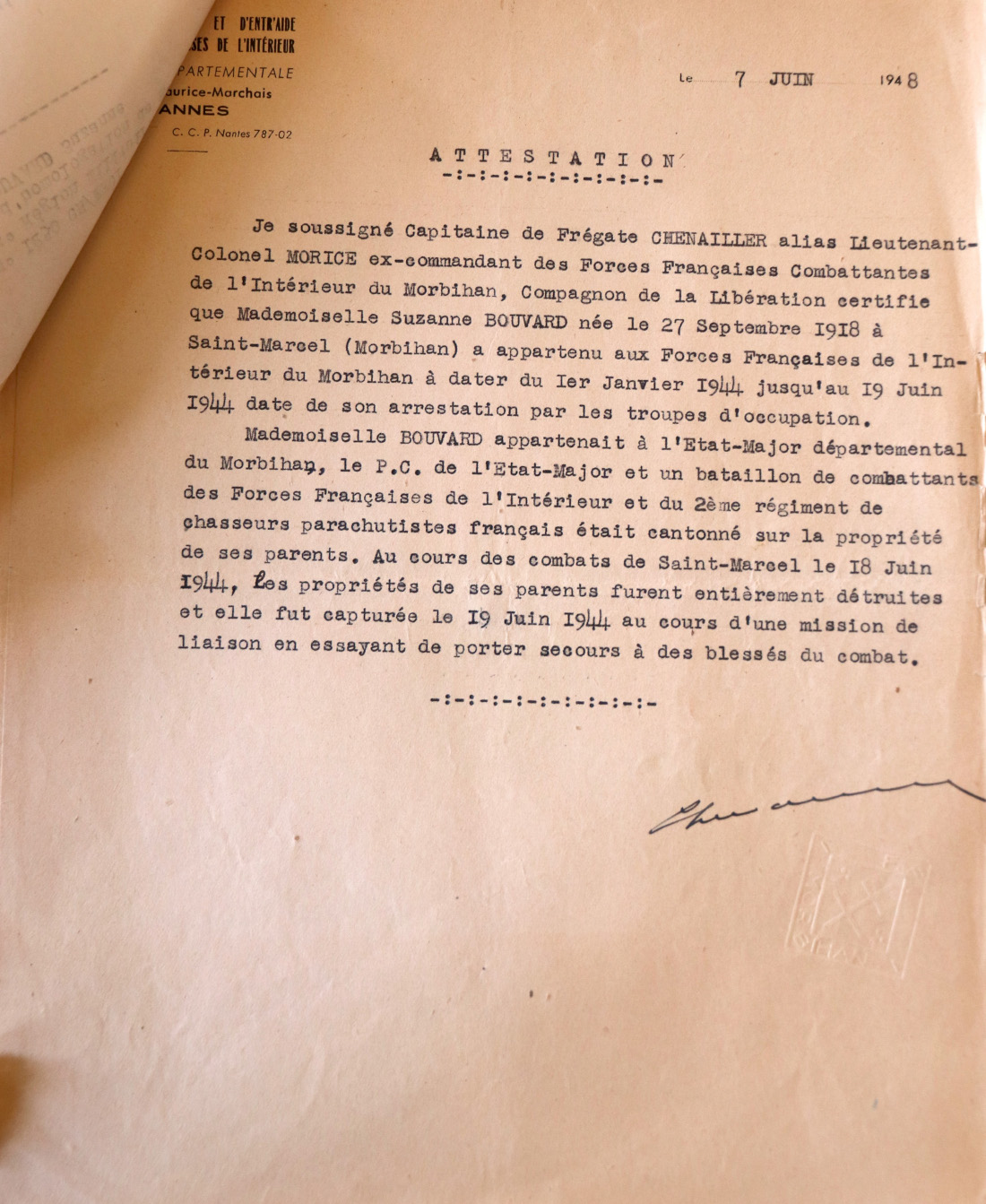

Certificate written by Paul Chenailler, alias Colonel Morice, commander of the FFI of Morbihan, describing Suzanne Bouvard's actions in the Resistance

(Service Historique de la Défense).