home together’ Suzanne and Simone,

a friendship at Ravensbrück Part 2

From Brittany to Ravensbrück

(Loïc Merlet)

In French

The last stop before hell

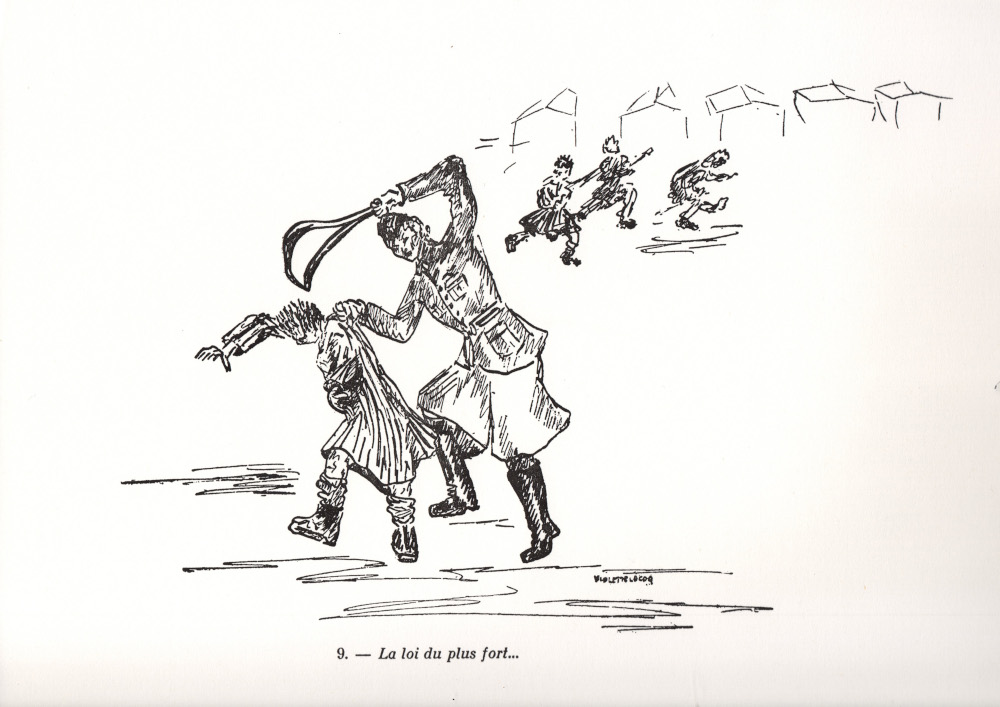

The first blows rained down on them with breathtaking violence. After the humiliation suffered during the Saint-Marcel battles, the Germans satisfied their desire for revenge by attacking the young women. Speaking to her teenage audience, Suzanne recounted these difficult hours with great restraint: “We were taken to the Feldgendarmes (the German military police, Editor's note) whose comrades had been killed the day before. We were beaten in a way I wouldn't wish on anyone. Well, that's just a detail, because you can recover from bruises.” In her memoirs, Annic said she lost consciousness after a series of slaps inflicted by an officer, then the interrogation resumed:

“Suzanne was ordered to enter a sort of small enclosure. When she reappeared, face bloodied, the blows having struck her nose, the marks of whippings, my heart clenched severely.”

Later in the day on June 19, they were handed over to the Gestapo and interrogated again. In the evening, they were placed in a cell that was teeming with bedbugs. The two cousins, who were more used to manor life, had to quickly adapt to their new reality. “I don't know if you'll ever find yourself in this situation, but it was peculiar for us because it was so crowded,” said Suzanne. “Fortunately, we were all women from Morbihan who were there for roughly the same reasons. That was a relief.” Suzanne and Annic met other women Resistance members from the region and made friends with them. But after a fortnight, they found out that they would be leaving Brittany.

On July 1, at 5am, they joined a group of around a dozen women gathered in the prison’s courtyard. They were taken to the railway station in Vannes, from where they boarded a cattle train and had to sit on “rotten straw”. Their long journey had begun. Fighting raged in Normandy and the Allies were progressively, and with difficulty, following the D-Day Landings in June. Their train was regularly delayed due to bombings. Despite the threats from their German guards, Annic remembered “fits of laughter”, “moments of genuine cheerfulness” and even a rendition of the Marseillaise (the French national anthem), sang “with bold defiance”. She even described the journey as a “pleasure train” in comparison with what awaited them. On July 10, the train finally reached Royallieu prisoner’s camp in the Compiègne department in the Oise region. The women’s section was full, so the group, still under heavy guard, was sent to the Fort de Romainville in Les Lilas, northeast of Paris.

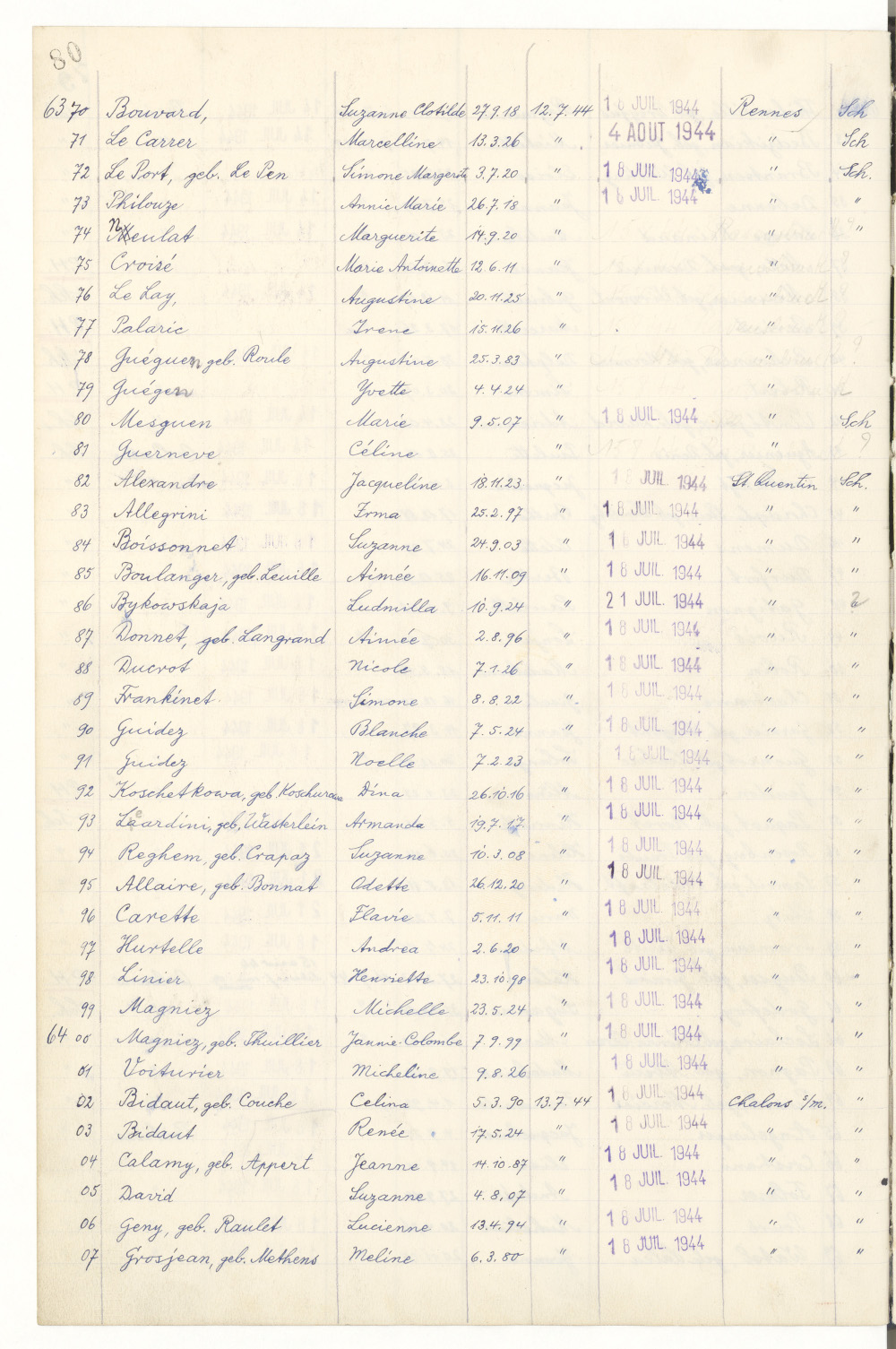

The register at the Fort de Romainville showing the arrival of Suzanne Bouvard and Annic Philouze, July 12, 1944.

(Archives nationales)

The camp was directly administered by the German army. It was where “active enemy elements of the Reich” were held prisoner, arrested for having acted against Nazi Germany or its army, or for having “endangered the maintenance of order and security”. As Annic sensed, this place was “the final stop before hell”. “This ‘pleasure train’ brought us to the edge of a long, long journey of suffering, horror and hatred”. For 12 days, the cousins were subjected to camp discipline. Wake-up, roll call, breakfast, shower, meals, another roll call. The food was decent, however, and the prisoners were allowed to walk around the fort’s courtyard. Now that the Allies had finally set foot in France, many of the female Resistance members thought they would escape deportation. But on July 18, they were rounded up once more. The two women from Brittany were grouped with about fifty women in a camp casemate, before departing for the Gare de l'Est in Paris. “It was bad luck because in August, France was liberated, but we had been taken to Germany. It was a matter of just two weeks. We were on the second-to-last convoy,” Suzanne remarked with bitter irony.

To view this video, please accept YouTube cookies.

Ravensbrück and the Kommandos

The transport conditions bore no resemblance to the “pleasure train”. Annic and Suzanne found themselves in a third-class carriage, “packed in like sardines”, where they endured both hunger and stifling heat. During the night of July 20-21, they crossed the Franco-German border. At Saarbrücken, the order was given to disembark. The Resistance women were brutally marched on foot to the Neue Bremm camp, run by the Gestapo. It was an immersion into concentration camp hell. Suzanne was seized with horror at the sight of “men with shaved heads, thin, frightful” who rushed towards them hoping to get something to eat. “We said to ourselves: ‘But is this what the camps are like?’ We wondered if we’d arrived on another planet. I couldn't believe that it was possible to treat people like this – like animals. They no longer looked like humans.”

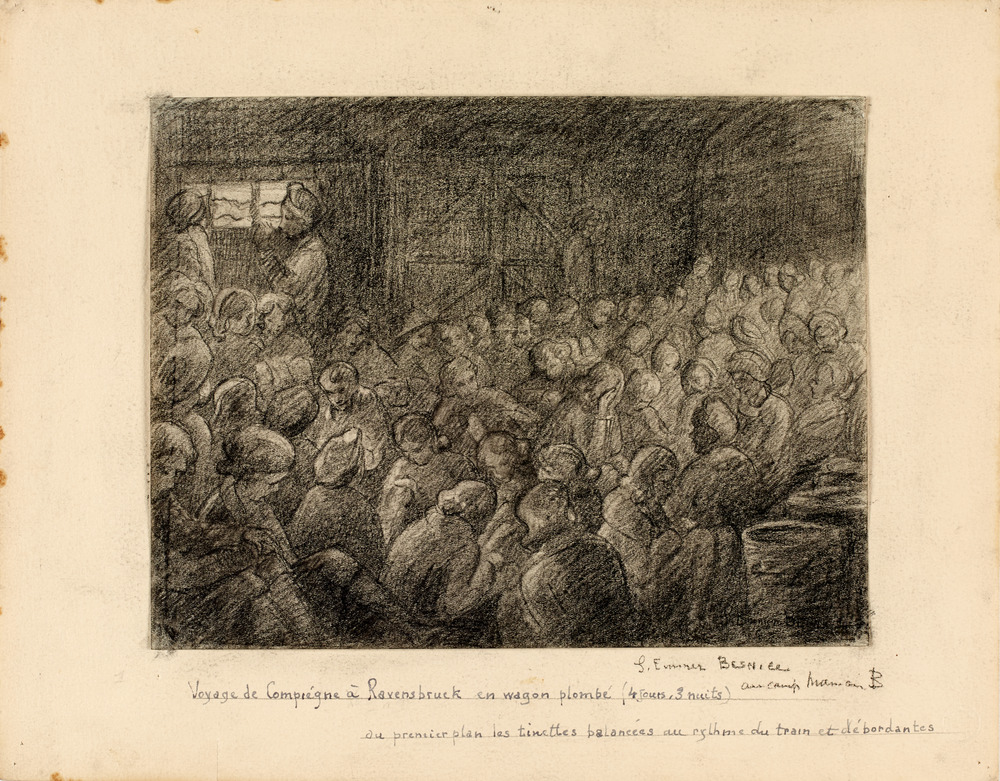

The journey from Compiègne to Ravensbrück in a cattle wagon

by Suzanne Besniée, deported to Ravensbrück on January 31, 1944.

(Centre national des arts plastiques, Hélène Peter)

Annic never forgot the “skeletal children in rags” who approached them. The new arrivals, consumed with pity, gave them whatever dry biscuits or bread they had. But the SS were watching: “They struck, they hit and they kicked them, tearing away their meagre rations and scraps of treasure.” Five days later, the French Resistance women were relieved to hear they would be leaving, believing they would never experience anything worse.

But their 72-hour journey in cattle wagons was a fresh ordeal.

“Torrid heat, forced proximity, lack of food, intensified smell from the buckets used as toilets,”

Annic recounted. But a furtive glimpse of the ruined city of Berlin, seen by removing some wooden boards from the air vents, brought hope to the passengers that the end of the war could be nearing. On July 30, at 4am, they arrived at Fürstenberg station, 80 kilometres north of Berlin. On the path leading to Ravensbrück camp, they once again discovered

“human beings with shaved heads, dressed in striped outfits.”

They mistook them for men, but they were indeed women. Built in 1939 on the orders of Heinrich Himmler, supreme commander of the SS, Ravensbrück was the largest concentration camp for women in the Third Reich. The Nazis imprisoned women Resistance members, prisoners of war, Jewish and Gypsy racial prisoners, as well as Jehovah's Witnesses, plus a few thousand men in an annex camp nearby. In total, more than 120,000 women deportees of about 20 nationalities passed through Ravensbrück until 1945.

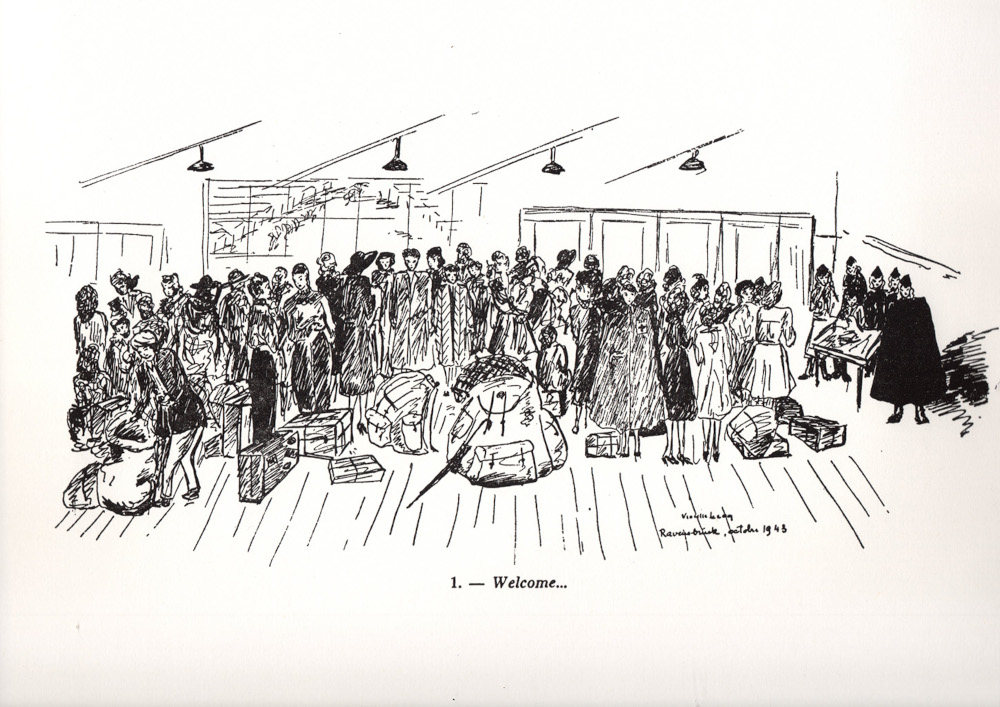

The arrival at Ravensbrück, as drawn by Violette Rougier-Lecoq, deported in October 1943.

These reproductions are taken from "Testimonies - 36 Pen Drawings - Ravensbrück", Paris, Les Deux sirènes, 1948.

The originals have been lost.

In French

(Musée de la Résistance et de la Déportation de Besançon).

At 6am, their fate was sealed. They passed through the heavy gates of the camp, surrounded by watchtowers from which guards kept watch day and night. Suzanne, Annic and their companions were searched, and everything was taken from them. “It was very uncomfortable. There were older women, some with their daughters. It was humiliating to find themselves completely naked. We wondered what kind of a place we had come to. It felt unreal,” Suzanne said. Then the two cousins were assigned a registration number: 47,329 for Suzanne, 47,372 for Annic. They were now just “Stücken” (pieces) always lined up in rows of five by five. Placed in quarantine in Block 23, they soon learned the hierarchy of the camp. The female guards, or “Aufseherinnen”, were SS women, “not fun at all”, according to Suzanne. The block leaders and deputy block leaders, the “blokovas” and “stubowas”, came from the ranks of the prisoners.

“With these women, when you were lucky, things went well, but when you were unlucky, they were just as bad to us as the Germans. They enjoyed special privileges and had only one thought in mind: to stay in good standing so as not to lose their advantages.”

Discipline was strict. They were woken at 3:30-4am for a first roll call session, after having swallowed a simple black juice, a kind of coffee substitute. The roll call could last a few hours. For two weeks, Suzanne and Annic were given different tasks. Suzanne had to take care of rabbit hutches, Annic helped build a wooden building, carrying heavy loads from 6am to 6pm, with a one-hour break to swallow a trickle of soup. The cousins then had to fill and push sand carts to the rhythm of the guards' “schlague” (whip), before being sent to extract peat. When they returned in the evening, there was another endless roll call, followed by a meagre meal. They spent evenings trying to remove lice from the straw mattresses where they slept two to a bed.

To view this video, please accept YouTube cookies.

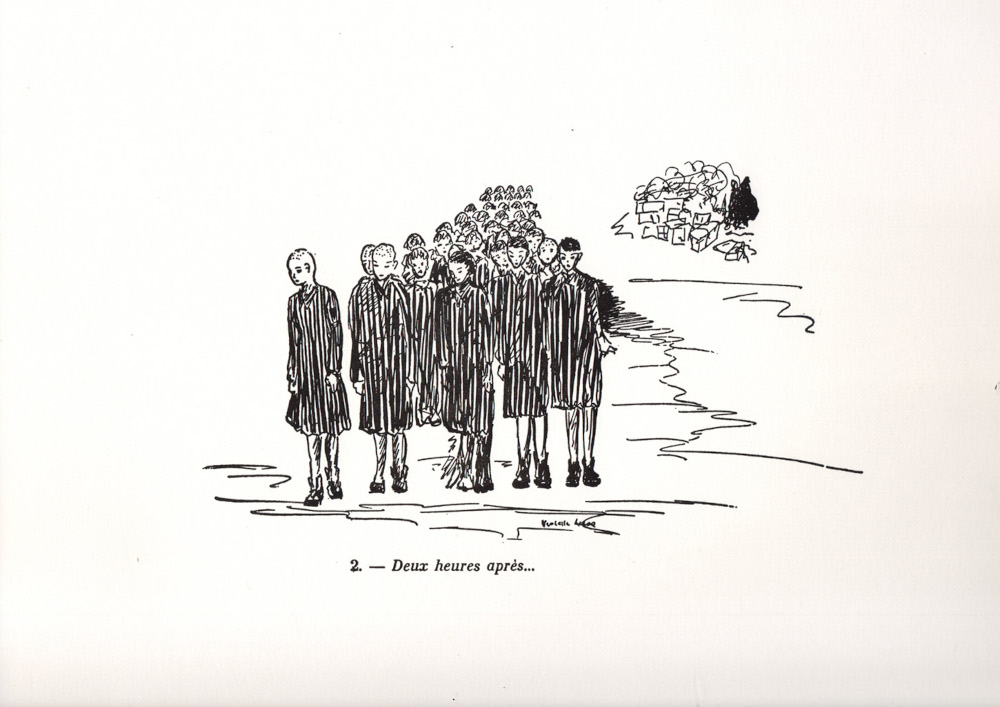

On August 14, 1944, they left again, this time to the Neubrandenburg camp, one of the 40 satellite work camps known as Kommandos under Ravensbrück's authority, 50 kilometres further north. Before leaving, they were handed the striped prisoners’ uniform, “our death garment in the eyes of the Nazis, since none of us was meant to leave their camps alive”, Annic said. She and Suzanne had to sew their registration numbers onto their new dresses along with a red triangle, the symbol for political prisoners. At nightfall, they arrived at the camp to the shouts of the female guards: 'Los! Raus! Schnell!' (Move! Out! Quick!) as blows rained down on their already exhausted bodies. The women now lived in a state of total shock. As Annie said:

“We were no longer human. We moved through the night like robots, aware that the right to die peacefully would be denied to us, having only the right to perish from exhaustion and suffering.”

The violence of the Ravensbrück female guards, depicted by Violette Rougier-Lecoq, deported in October 1943. These reproductions are taken from "Testimonies - 36 Pen Drawings - Ravensbrück", Paris, Les Deux sirènes, 1948. The originals have been lost.