Video: the investigation

Video: the investigation

Louise’s life came to an abrupt end on a winter’s day in 1944 when she was 16 years old. In the years that followed, her memory was lost to all but a handful of former classmates and her teacher, Miss Malingrey. Seven decades later, it has suddenly been brought back to life inside the very high school where she studied. A new generation of pupils is being touched by her story.

After months of tracing Louise’s footsteps, librarian Khalida Hatchy is still deeply consumed by the young girl’s life. “It’s like a quest for truth,” she explained. “I feel a duty to look for more information. What happened to her that day? I have tried to shed light on the past”. The quest for Louise’s story led Khalida on to further trails. She discovered the names of other Jean de La Fontaine pupils who were also deported. “Louise took us to their stories through her letters. It’s been fascinating.”

Searching the Paris Archives, the determined librarian came across a note on the school’s “lost pupils”, written by a former head teacher at Jean de La Fontaine shortly after the Liberation. She found two names: Louise’s little sister, Lucie, and Hélène Poulik, who was a year older than Louise when she was arrested and deported to Auschwitz, along with her mother, in 1942. An account written by a literature teacher for the school’s fiftieth anniversary mentions another pupil who “never came back”. Anna Janowski was 13 years old when she was deported in Convoy no. 15 on August 5, 1942.

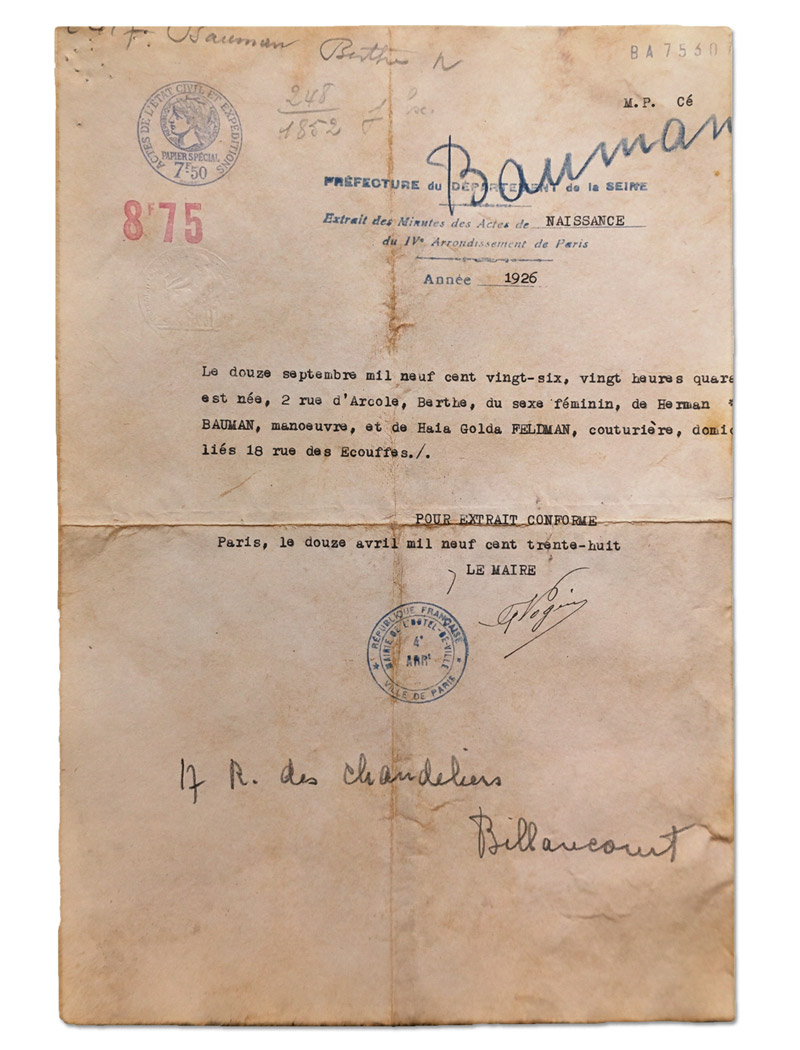

Determined to leave no leaf unturned, Khalida decided to get current pupils involved in this “quest for the truth”. Her apprentice detectives poured over wartime school yearbooks and a few civil status documents found in an old box. Eventually they were able to add a fifth name to the list of former pupils who perished during the Holocaust.

Berthe Baumann was born in Paris in 1926. She was a year above Louise Pikovsky at Jean de La Fontaine when she was deported from Drancy on August 28, 1942, in the same convoy as Hélène Poulik. “In the beginning, when we started our research, we were desperate to find someone, so we could show our work had been fruitful. But when we found her we were heartbroken, because we knew she must have suffered,” said Colombe and Romane, the two girls who made the discovery. “We imagined pupils of her age being deported today, our own little brothers and sisters,” they added. “People tend to think that this period in history is far behind us, but it isn’t really.”

By the end of the school year, Colombe and Romane will see their efforts rewarded when a plaque bearing the names of the five deported pupils is finally unveiled. Jean de La Fontaine is one of the few Parisian schools not to have one. The names of Louise, Lucie, Hélène, Anna and Berthe will henceforth be engraved in the school’s entrance hall – an indelible tribute to their short lives and a reminder of their tragic fate.

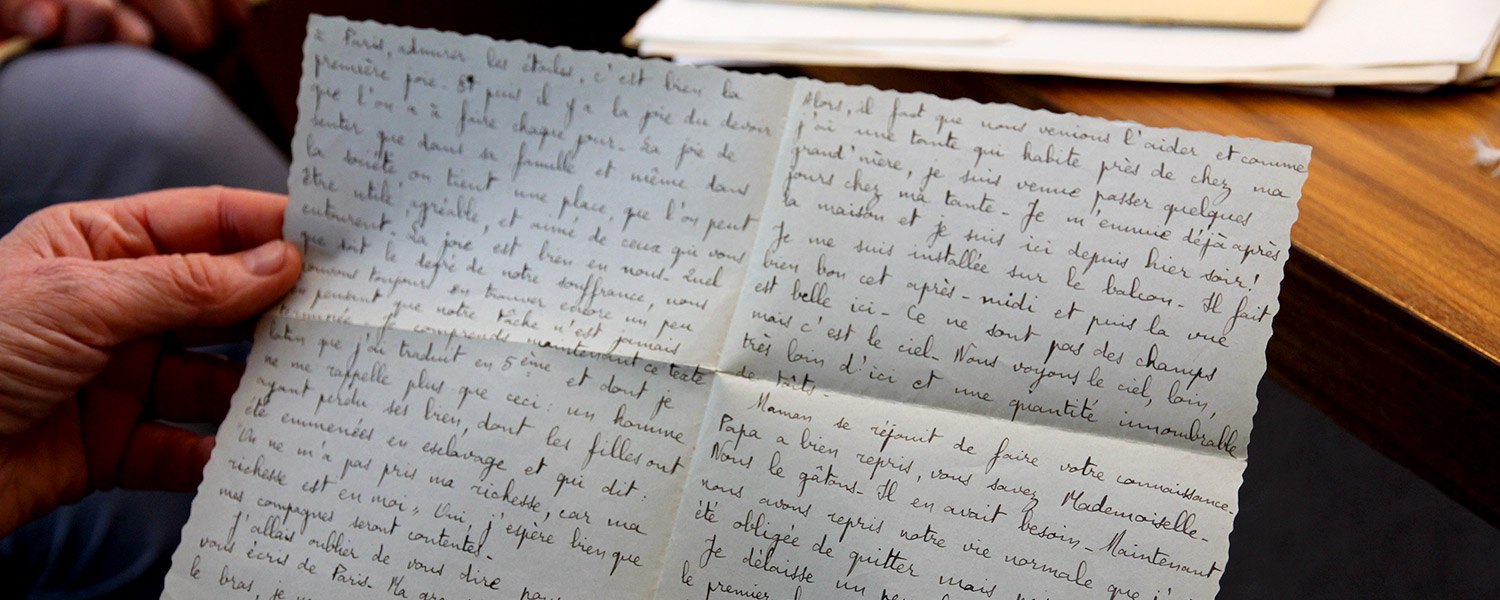

Our mission was not entirely over. Khalida and I still had one fear, that Louise’s letters might once again end up buried in a forgotten cupboard under a layer of dust. To prevent history from repeating itself, we decided, in agreement with the school, to donate the letters to the Shoah Memorial in Paris, along with the class photo and Bible the young pupil had left with Miss Malingrey. Christine Lerch, the first person to have found Louise’s writings, was present as we handed over the documents, along with her colleague Patrick Choukroun, a music teacher at Jean de La Fontaine, who supported her in her efforts to preserve the letters and find out about their author.

“When I found the letters I was shocked,” said the retired Maths teacher. “I didn’t want to leave them with someone who might not give them the importance they deserve. When I retired, I was wondering who would look after them. Now I am relieved to know that they are in the right place, and that so much has been discovered about Louise. The important thing was for her memory to come back to life.”

Karen Taïeb, who runs the Shoah Memorial’s archives, is used to receiving family donations. But for a school to deposit its archives is a first. “Each of these letters reveals not only a victim, but a life,” she said. “Personally, I feel a letter says a lot more about a person than a picture. It is a direct link with the person who held the crayon and wrote down each word. Not all letters are of equal interest, but they are often the only threads of life we have for those who were deported.”

As we left the Shoah Memorial, we cast one last look at the wall that bears the names of the 76,000 Jews – 11,000 of them children – who were deported from France between 1942 and 1944. Louise’s name sits alongside those of her parents, her brother and her sisters. The war extinguished her thirst for knowledge and denied her a promising future. But after decades of silence, the young pupil is now a lot more than a name. “Her story is now accessible to all pupils, today and in the future,” said Khalida. “It is a tale of courage, of endurance through hardship, and of faith in life.”