Video: the investigation

Video: the investigation

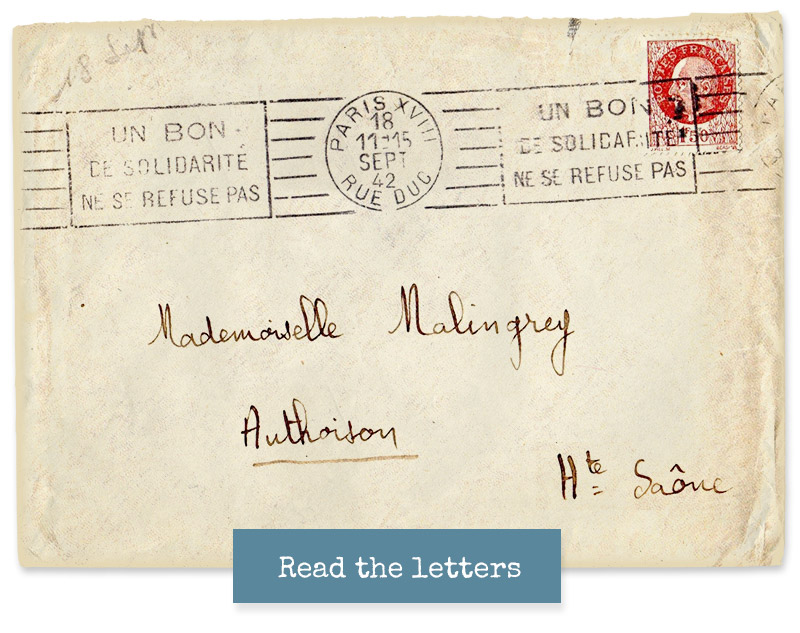

All the letters are addressed to one person: Miss Malingrey. Two yearbooks dated 1941 and 1942, also found in the cupboard, indicate she taught Latin and Greek at Jean de La Fontaine high school. Louise and Miss Malingrey corresponded during the summer of 1942. The first letter dates from August 7. Louise writes: “Dear Miss, I received your letter and parcel and I can’t thank you for one or the other. But may I tell you that the beans were delicious? And the letter… Oh! I can’t say anything at all because I would overstep the limits you set.” Through her words, the young pupil reveals her personal thoughts and interrogations. She does not write explicitly about the war, but a sense of the conflict gradually emerges.

Three weeks after 13,000 Jews were arrested in and around Paris during the so-called Vel d’Hiv round-up, on July 16-17, 1942, Louise informs Miss Malingrey that her father was among those taken by police: “We have some news of father. He has not left Drancy (…) We were able to send him a parcel of clothes. I had to do a lot of work to get the parcel ready, but it was such a joy to do so.” Louise does not openly express her anguish, but the occasional allusion sheds light on her worries: “Oh! Miss, if you could talk to me again about happiness. I’m sure we can appreciate happiness after we’ve suffered, but does suffering ever end? I’m beginning to doubt that. With all my love and best wishes, Louise.”

A month later, Louise’s tone is lighter. In a letter dated September 1, she describes a stroll she and her father took in the hope of finding Miss Malingrey at home. But her teacher was on holiday at the family house in Haute-Saône, in eastern France. “You live in a lovely neighbourhood, Miss, I went on a pleasant walk with father from the Place de l’Étoile to your home. When we got there, I was disappointed,” she writes, referring to her teacher’s absence.

Louise does not go into details, but evidently her father has been allowed to leave the internment camp in Drancy. She never refers to his imprisonment again in her letters. Instead, the teenager stresses her yearning to learn: “I would like to read, read, and stop only to think about what I’ve read.” Louise is bored during the summer holidays and is impatient to return to class. At 15, her concerns are not those of a typical teenager. She asks Miss Malingrey about the meaning of religion. She expresses doubts about her own Jewish faith. “So many things displease me about people who believe and practise. My grandmother for example would fall ill if she knew we were writing on a Saturday. And all the established practices from days gone by, there’s no reason for them to exist today!” she confides in her teacher. “All of this bothers me so much that for a long time I’ve wondered. But you’ve convinced me… I believe that God helps us, even if I don’t believe He hears us.”

Is Louise searching for answers to understand what is happening during the Nazi Occupation? Does she realise the danger her family faces? A few letters later, her words about the deprivation of freedom sound almost prophetic today: “I think the Greeks were right to consider not seeing the sun as the worst suffering of all. Oh yes! To be able to smell the scent of grass, see the sun in the fields, watch the sunset in Paris and gaze at the stars are the biggest joys of all. Joy is within us. Whatever the extent of our suffering, we can always find joy in the knowledge that our work is never over (…) I now better understand a text I translated from Latin in 5e [The class Louise attended when she was 12 to 13], of which I can only remember this: A man, who has lost his possessions, and whose daughters have been enslaved, says: ‘They have not taken my wealth, because my wealth is within me’.”

Louise’s letters suggest she was particularly mature for her age, but adolescent anxieties peep through from time to time. She tells her teacher she sometimes feels lonely and misunderstood by her classmates: “In my three years at high school, there has not been a single person I could call a friend. Perhaps I am too demanding and self-centred?”

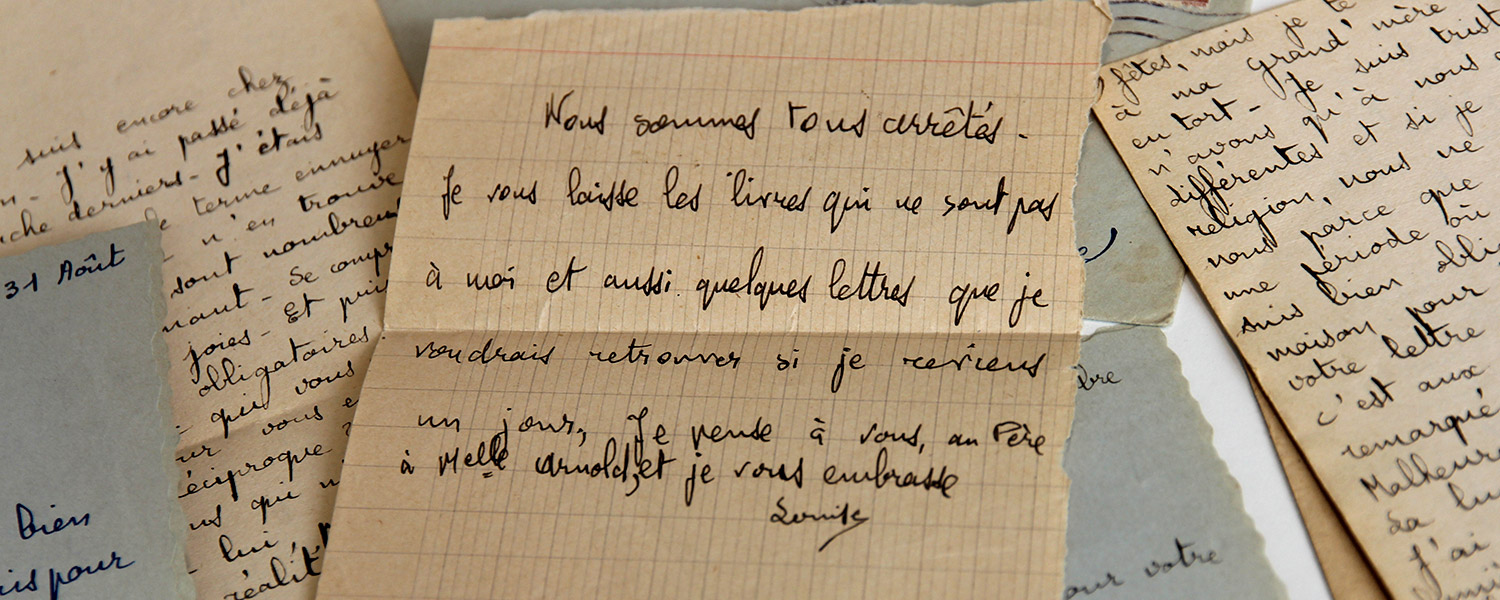

The last summer holiday letter dates to September 19, 1942, when classes were starting up again. It is followed by one more note, stuffed inside an unstamped envelope, with “January 1944” scrawled across it in pencil. Louise’s handwriting is shaky: “We have all been arrested. I’m leaving you the books that are not mine and some letters I’d like to find if I ever come back. I’ll think of you, of Father and Miss Arnold. All my love, Louise.”

Françoise Szmerla compares her cousin to Anne Frank. Through their writing, it is clear the two had a lot in common. They both had a hunger to learn. They both questioned religion and felt they had never found a real friend. They both died after being deported. In publishing her diary, Otto Frank allowed his daughter’s memory to live on after her death. Louise’s father did not survive the Holocaust, but her teacher, Miss Malingrey, kept a piece of her memory alive by holding on to her letters.

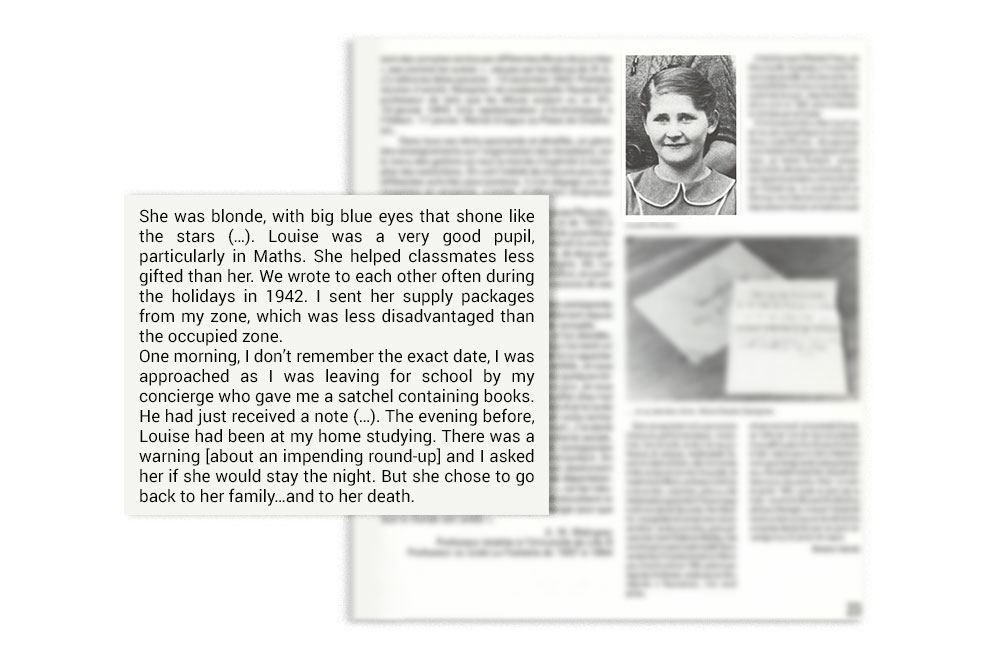

In 1988, as Jean de La Fontaine celebrated its fiftieth anniversary, Miss Malingrey decided to leave Louise’s letters with the school, more than four decades after last seeing her. She wrote a paragraph about Louise, her pupil between 1941 and 1943, in a special anniversary brochure: “She was blonde, with big blue eyes that shone like the stars (…). Louise was a very good pupil, particularly in Maths. She helped classmates less gifted than her. We wrote to each other often during the holidays in 1942. I sent her supply packages from my zone, which was less disadvantaged than the occupied zone,” the teacher explained, referring to the wartime separation between the Nazi-occupied northern half of France and the southern half controlled by the Vichy regime. “One morning, I don’t remember the exact date, I was approached as I was leaving for school by my concierge who gave me a satchel containing books. He had just received a note (…). The evening before, Louise had been at my home studying. There was a warning [about an impending round-up] and I asked her if she would stay the night. But she chose to go back to her family…and to her death.”

Miss Malingrey, whose first name was Anne-Marie, died in 2004 aged 98. Not long before she passed away, she gave a photo of Louise to the Shoah Memorial in Paris. She visited the Memorial, Europe’s leading Holocaust museum and archive, to make the donation with a group of former pupils. Colette Montavon-Schirmann was one of them. “Miss Malingrey was an old and special friend. There was a group of five of us. We kept in touch until her very last days. We loved her,” she said. “I actually became a Latin and Greek teacher thanks to her. She gave me the passion and the desire to share my knowledge with others.”

Miss Malingrey never married or had children, but she became very close to some of her former pupils. They enjoyed her imaginative teaching methods, considered very modern in the 1940s. “As a teacher, she was ahead of her time. She had a brilliant sense of humour and was very lively. Her colleagues were not like that,” Collette recalled.

After the war, Miss Malingrey obtained the prestigious status of Emeritus Professor at the University of Charles-de-Gaulle in Lille. A recognised expert in Early Christian Greek literature, she was, according to her former pupil, “driven by her faith”. She was particularly interested in the Fathers of the Church and how they related to Judaism. And while she and Louise did not share the same faith, the fact that they discussed religion in their correspondence did not come as a surprise to Colette, for whom Miss Malingrey’s sparse references to Louise after the war concealed the strength of their bond.

“She never spoke about what happened [to Louise] because it was particularly painful for her. She was a very discreet woman when it came to pain or grief, but one day she showed us Louise’s satchel,” Colette said. Until her death, the memory of Louise’s sudden disappearance haunted Miss Malingrey: “It was the biggest regret of her life. She was so upset with herself for not having insisted that Louise sleep at her home that night.”