Video: the investigation

Video: the investigation

Madeleine was a good friend of Louise’s but she did not know much about her family. Louise rarely talked about them. Who were her parents? Where were they from? We managed to find a distant relative, Nicole Minot, on a genealogy website. She had done some research on the Pikovskys. Her grandmother, Hanna Pessia, was the aunt of Louise’s father, Abraham. For years, she had been trying to trace the family’s footsteps. “They were originally from Rotmistrovka in Ukraine. It’s a town south of Kiev,” she explained. “My grandfather, Moshe Fuchsmann, arrived in France in 1905. His wife arrived a year later. They had to leave their country because of the pogroms.”

Jews had become a target in Ukraine, then part of the Russian Empire. The first anti-Jewish riots, known as pogroms, took place after the assassination of Tsar Alexander II. Between 1881 and 1884, Jews were massacred in many towns and villages. The Jewish community had become a scapegoat for political instability in the empire. It was in this climate of fear that Louise’s father, Abraham, was born on December 17, 1896, in Nikolaev, a large town in southern Ukraine, 300 kilometres from Rotmistrovka.

The Pikovsky family decided to flee when another wave of pogroms started up in the early 20th century. With his siblings and parents, Abraham headed west. According to documents from the archives of the Paris Police Prefecture, Louise’s father “appears to have entered France on October 4, 1921, and was given a residency permit.” However, several other documents suggest Abraham had been living in the French capital well before 1921.

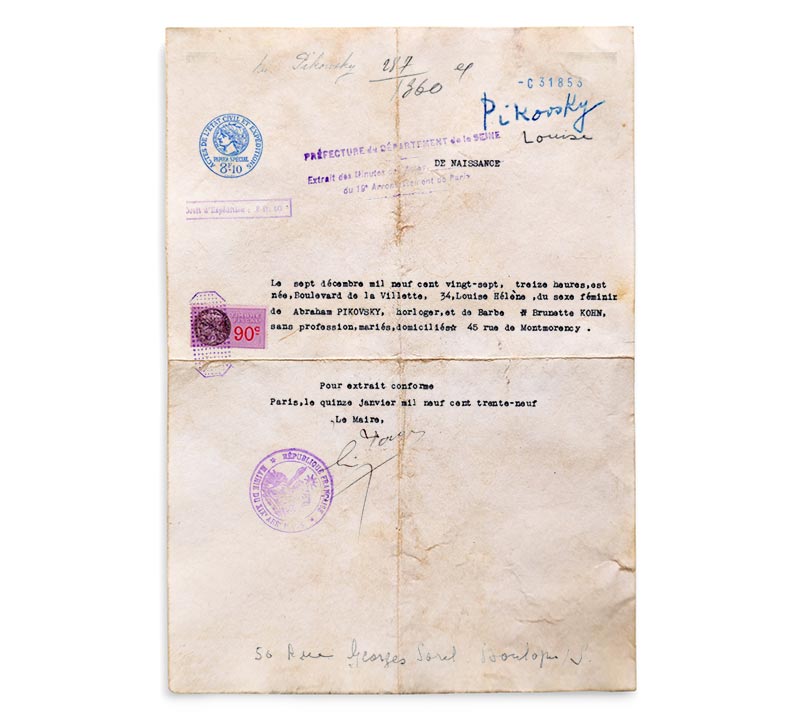

He appears as Albert, a Gallicised version of his name, on the 1918 death certificate of his mother, Hanna Abramowsky (also spelled Abramoff). The certificate was issued by the town hall in the 20th arrondissement of Paris. We also found a trace of him on a marriage certificate issued a year earlier, thereby discovering that Louise’s mother was his second wife. At 23, the young Abraham married Hélène Moch, a 20-year-old typist. She died in 1923 before the couple had had any children. Two years later, Abraham exchanged marriage vows again. On March 17, 1925, he married Barbe Brunette Kohn in the 18th arrondissement. She worked in a bank, was the daughter of a diamond merchant and the granddaughter of the Chief Rabbi of the Haut-Rhin department, on France’s eastern border with Germany. The couple had four children: Annette in 1926, Louise in 1927, Jean in 1929 and Lucie in 1932.

His children’s birth certificates show that Abraham frequently changed jobs. After working as a shop clerk, he went into clock-making. He then got a job as a taxi driver for a firm in Courbevoie on the northwestern edge of Paris. Driving taxis was a common occupation for members of the Russian immigrant community.

Electoral registers from 1939 show that the family lived for a few years in the central Marais district of Paris, and then moved to just outside the city in Boulogne-Billancourt, close to the French capital’s 16th arrondissement. They lived first at 53 rue Georges Sorel, before moving across the street to number 50. They were living there when war broke out. We found the names of a few neighbours from census data gathered in 1946. Liliane Giura lived at number 49 rue Georges Sorel. Like many children in the neighbourhood, her parents worked at the Renault car factory in Boulogne-Billancourt. She was born in 1927, the same year as Louise, but she did not remember her when we got in contact. “She might have been in the same class as me, but my memory fails me,” she apologised. The elderly woman remembered seeing “the Germans driving through the streets of Boulogne, but I didn’t see any arrests or anything like that.” Marius Wellem lived at number 18 and told us German soldiers lived in his building. “They put a big light on the roof to look for Allied aircraft,” he said. “We knew when air raid warnings were about to come because we would hear the motor make a big noise.”

We did not manage to speak to any current residents of number 50 who knew Louise. Most of her old neighbours have passed away and many of those who live there now have no links to the building’s past. We bumped into the president of the residents’ committee in the hallway and he was surprised to hear the Pikovsky’s story, even though his grandparents lived in the building at the same time as Louise. The building’s entrance, stairway and letterboxes remain unchanged, but traces of Louise’s years there have been lost with time.

The Pikovskys suffered their first major blow during the summer of 1942. We know from reading Louise’s letters that her father was imprisoned and later released from the Drancy internment camp. But we did not find any documents related to his internment at the Paris Police Prefecture, France’s National Archives or the Shoah Memorial.

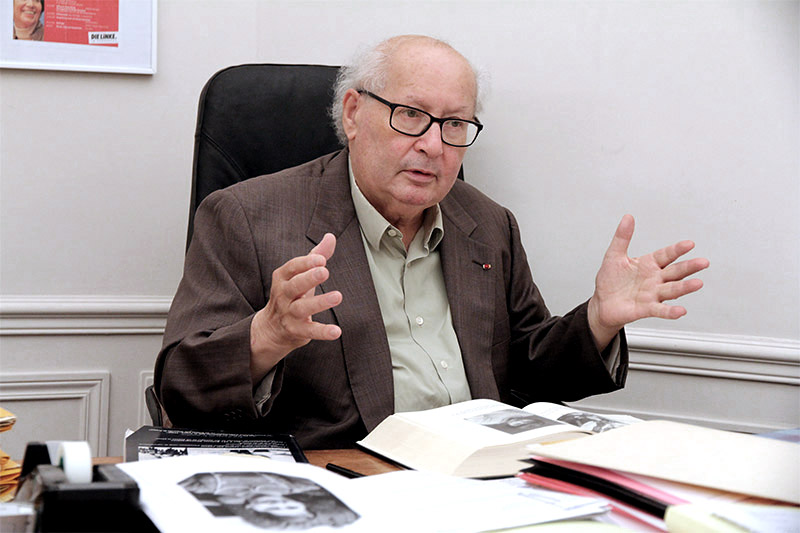

How did this episode escape the notoriously meticulous bureaucracy of the Nazis and their Vichy allies? To find out, we contacted an expert who has dedicated his life to documenting the Holocaust. Along with his wife Beate, Serge Klarsfeld has worked tirelessly for decades to expose and prosecute Nazi criminals, and preserve the memory of their victims. “In August and September 1942, so many people were arriving in Drancy and there were so many convoys, up to three or four a week, that the officer in charge failed to keep track,” Klarsfeld explained. “Individual records were not being issued. It was the camp’s secretary who then took on the job of drawing up individual records using deportation lists. So it is not surprising that some names are missing, particularly those of people who were able to leave the camp.”

In her letters, Louise does not give any details as to how or why her father was released. Klarsfeld believes he was freed in 1942 because he had been naturalised. “At that time, they had not started deporting French citizens.” The government’s Journal Officiel shows Abraham acquired French nationality in 1937, a few years before he was arrested. But a law signed by Philippe Pétain, the Vichy leader, in 1941 meant that Abraham had his nationality revoked. In a matter of months, more than 15,000 people, some 6,000 of them Jewish, lost their status as French citizens.

Serge Klarsfeld thinks it is likely that Louise’s mother “contacted the director or officer in charge at Drancy to tell them the couple’s children were French. Someone from the UGIF may also have got involved.” The UGIF (Union Générale des Israélites de France) was established in 1941 on Nazi orders to regroup all of France’s Jewish organisations into a single unit. All Jews in France were forced to join it. We found a document that suggests Klarsfeld’s guess is correct. In a letter dated July 20, 1942, Barbe Brunette Pikovsky wrote to the UGIF after her husband was arrested “last Thursday”, or July 16, during the infamous Vel’ d’Hiv round-up. “I’ve found myself alone with my four children,” she wrote. “We all have French nationality. A friend found me a little job and I earn 30 francs a day [roughly equivalent to 8 euros today]. I worked in a bank for eight years as a secretary and assistant accountant. Perhaps you would be able to find me some work?” In this letter, Barbe Brunette does not ask the UGIF to intervene and release her husband from Drancy, but perhaps she found another way or asked someone else. “It would not have been exceptional,” said Klarsfeld. “There were quite a few occasions when a prisoner was set free after someone intervened on his or her behalf.”

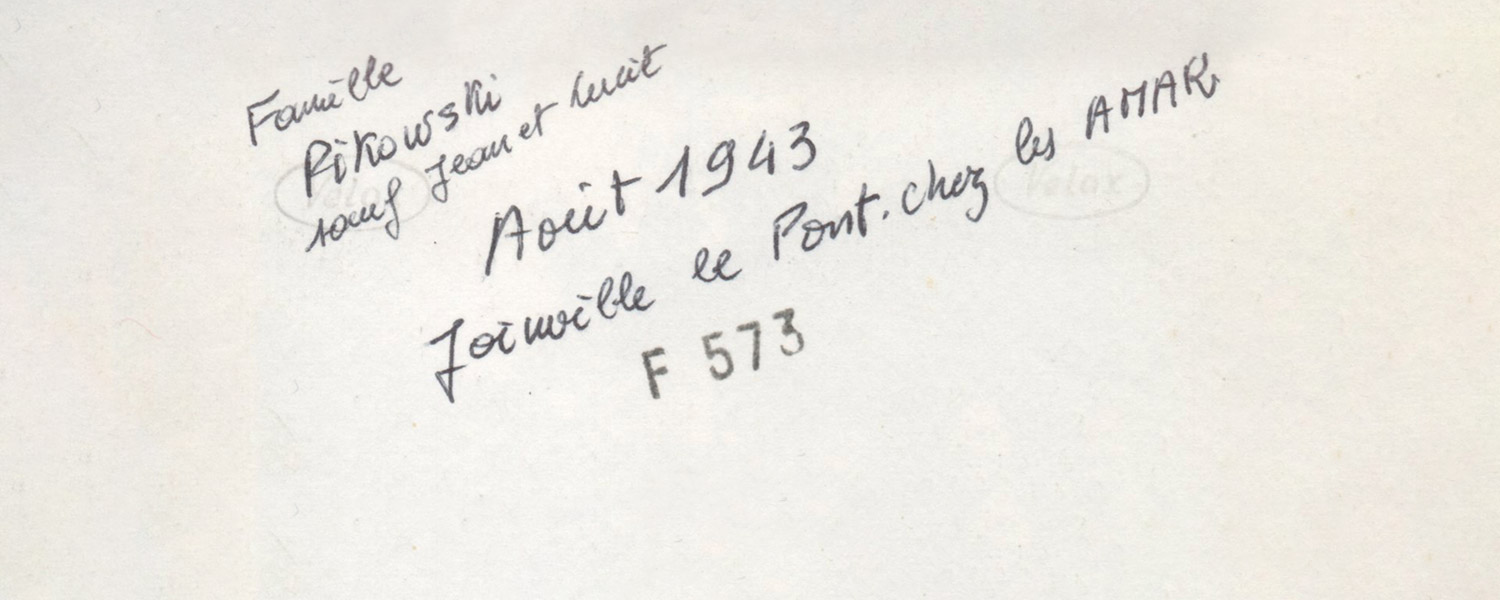

For nearly two years after Abraham was released, the Pikovsky family continued to live in Boulogne-Billancourt. Louise carried on with her studies at Jean de La Fontaine. During this time, she paid a visit to a distant cousin, Claude Counord, whom we tracked down using the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial website and a French phone directory. Claude’s grandmother was a cousin of Abraham’s mother, Hanna Abramoff. She told us she remembered meeting the Pikovsky family and to prove it, she sent us a photo taken in the Paris suburb of Joinville-le-Pont in August 1943. Claude is posing next to Louise, Louise’s sister Annette and their mother, Barbe Brunette. For the first time, we were able to see what Barbe Brunette looked like. It was an emotional moment for us.

Louise’s father, Abraham, and her two younger siblings, Lucie and Jean, are not in the picture. Claude saw Abraham that day and believes he must have been behind the camera. “They came to see us. They were very calm, discreet people. Abraham was particularly self-effacing. He was very thin, fragile, but very sweet. And the girls were really nice and smiley”, she recalled. The photo shows family members enjoying each other’s company on a beautiful summer’s day. But some of their relatives had already disappeared.

Claude’s uncle and aunt, Maurice and Mina Vozlinski, who were witnesses at Abraham and Barbe Brunette’s wedding, were deported to Auschwitz on July 24, 1942. Ten members of the Abramoff family line died in the Nazi death camps. By a miracle, Claude escaped the same fate: “We somehow managed to live through the war and I just carried on going to school. I didn’t miss a single class. I even passed my brevet [end-of-school exam] wearing my [yellow] star. When I took my singing test, my teacher congratulated me for being there.”

But the Pikovskys were not as lucky. By winter, the beautiful summer days were long gone. Marguerite Kohn, Danièle and Françoise’s mother, described the misfortune that befell the family in her memoirs, ‘Nous, les rescapés’ (‘We the Survivors’), which she wrote for her children shortly before passing away in 1993. “In Paris, my mother-in-law fell severely ill. She died surrounded by her children. We observed the customary days of mourning and then went back to our respective homes. My sister-in-law, Barbe Brunette, went back to her husband and their four children,” she wrote.

“That very same day the Milice came to their house. They took the father and told the mother to get the children ready because they would be coming back later to pick them up. Some neighbours, who must have had an idea of what would happen to them, tried to urge my sister-in-law to hide the children before the Milice came back. It was a lost cause! Brunette, probably still deep in mourning, refused to leave her house: ‘We will not be separated!’ she said. When the Milice reappeared, they were probably surprised to find them all still at home. It was 1944, a few months before the Liberation! If only they could have held out a little longer.”

Marguerite Kohn’s memoirs describe the exact circumstances in which the Pikovskys were arrested, though she confuses the Nazi-allied paramilitary Milice with ordinary French police, who actually carried out the arrests. How did she come by such details? Her daughters do not know and we could not find any official statements referring to the arrest. But her memoirs explain how Louise was able to go to Miss Malingrey’s home to leave her last letter and a few books, in between her father’s arrest and her own. They do not specify the exact date the Pikovskys were arrested, so we looked up a police register of arrivals at the Drancy camp and found that all six Pikovskys had entered the camp on January 22, 1944.

In one of his major studies “The Calendar of the Persecution of Jews in France, 1940-1944”, Serge Klarsfeld explains that the overnight round-up on January 21-22, 1944, “provided Drancy with 500 more victims” from the Paris region. But the Pikovskys had escaped previous raids, so why were they suddenly arrested? According to Klarsfeld, the situation had changed. “The Paris Police Prefecture, under pressure from the Germans, was struggling to find foreign Jews because more and more were going into hiding,” he explained. “There were fewer people to arrest, so the police targeted those who thought they were safe. After first going after the stateless, they started arresting those who had been naturalised but lost their French nationality.” That was Abraham’s case. He believed he was protected because his wife and children had French nationality, even if he no longer did.

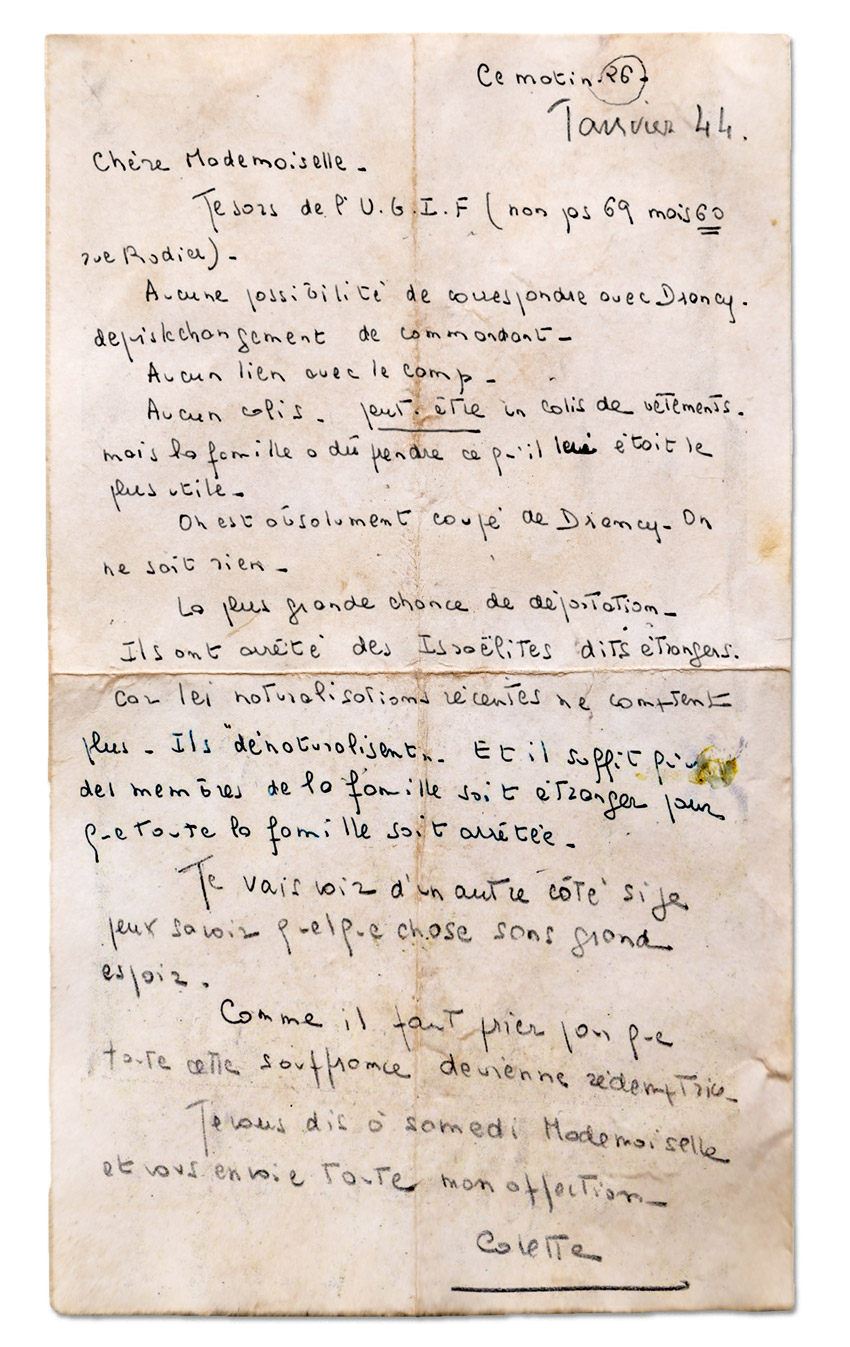

A letter, written by a former pupil of Miss Malingrey’s, who had since become a social worker, confirms this hypothesis. When Miss Malingrey asked her for help corresponding with Louise in Drancy, she received a very clear answer: “We are completely cut off from Drancy. We don’t know anything. Deportation is the most likely scenario. They have arrested all the Israelites deemed foreign because recent naturalisations no longer count. They take away their nationality and it only takes one family member to be foreign for the whole family to be arrested,” the social worker wrote on January 26, 1944. Miss Malingrey had done what she could, but it was too late.