Video: the investigation

Video: the investigation

Danièle Schlammé and her younger sister, Françoise Szmerla, have gathered for a special occasion. The two elderly siblings sit and wait patiently at the table of a small apartment in an Orthodox Jewish neighbourhood of Jerusalem. A few days ago, they received a phone call out-of-the-blue from France. Letters written by their first cousin, Louise Pikovsky, had been discovered in a Parisian high school.

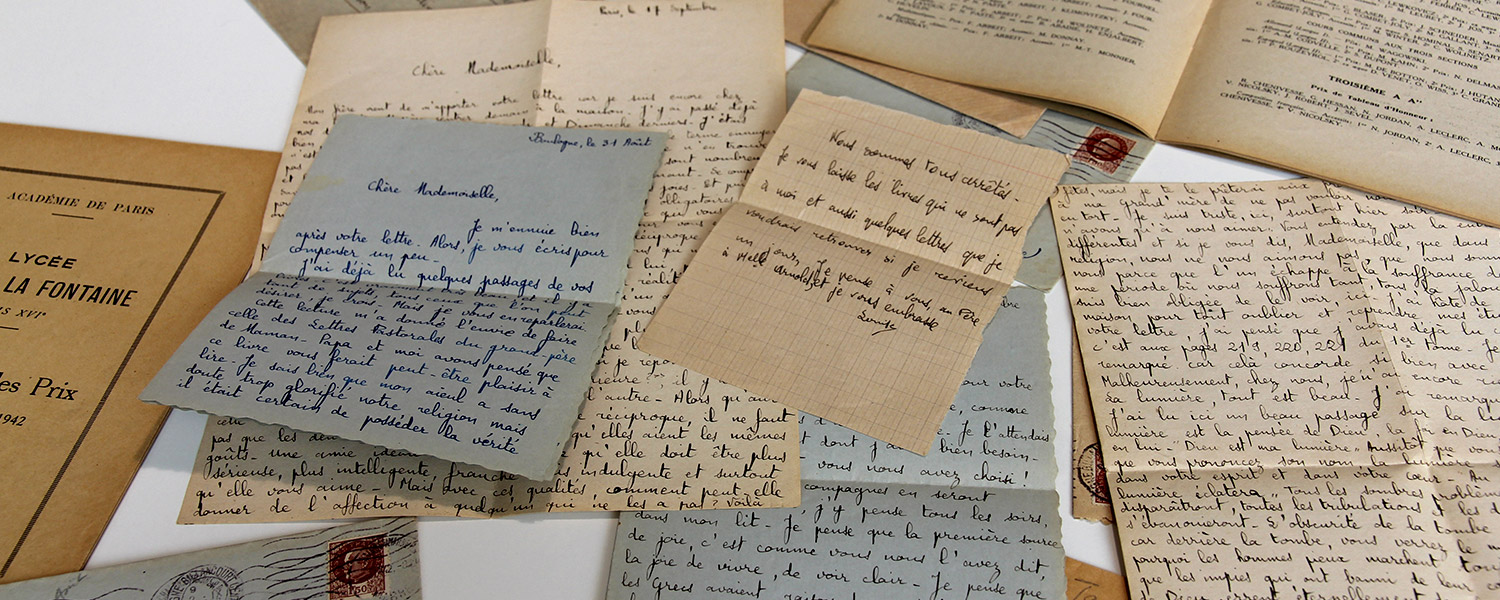

With trembling hands, they begin reading the letters penned during World War Two. Danièle cannot not take her eyes off them. She reads, silent and concentrated. Her younger sister, herself 80 years old, is bursting with excitement: “It’s incredible!” she gasps. “I can’t wait to read them all.”

The two sisters can finally learn about their long-lost cousin, in her own words. “We don’t remember her. Our mother talked about her, but that was it. We just have a photo of that part of the family,” Françoise explains, pointing to a picture yellowed with age. “There you have the Pikovsky children: Louise, Annette, Lucie and Jean. They were all deported when we were in Lyon,” says the elderly Frenchwoman, who has been living in Jerusalem for the past decade.

Danièle and Françoise, born Kohn, are both Holocaust survivors. Their father, Samuel Kohn, was arrested in February 1943 during a raid ordered by Klaus Barbie, a notorious Nazi commander, in the city of Lyon. He was deported to Auschwitz in November of the same year. Overnight, their mother, Marguerite, found herself alone with their children. She managed to take them to safety in Chambon-sur-Lignon, a village in the Massif-Central that later became famous for having sheltered many Jewish children during the war. “We were very happy there. Everyone was wonderful to us. It’s the only French village to have been honoured as Righteous Among the Nations,” says Françoise, referring to the prestigious title given to people who helped save Jews during the Holocaust.

Françoise is not bitter. Rather, she has a strong desire to live life to the full. “Our mother always told us to stay happy!” she says, bursting into laughter. And yet, the sisters have not had an easy ride. Their father never returned from Auschwitz and they lost many other relatives during the Holocaust. Their mother kept a record of the 14 family members who died during the war, their names listed on a sheet of paper soberly titled “My loved ones who disappeared”. Louise is there, alongside her parents and siblings. Discovering the existence of letters written by a relative from that list, more than seventy years later, is an unexpected gift. “We are overwhelmed,” says Françoise. “We have our very own Diary of Anne Frank in the Kohn family.”

In the living room of the Jerusalem apartment, Khalida Hatchy struggles to contain her emotion. It is thanks to her that the letters have found their way to the Kohn sisters. A librarian at the lycée Jean de La Fontaine, a high school in the 16th arrondissement of Paris, she has come from France with the letters. “A piece of their family’s history has been returned to them,” she says, shortly after meeting the sisters.

That slice of family history could easily have vanished forever. Khalida came across the letters by chance in February 2016. Six years earlier, a Maths teacher had found the letters, along with yearbooks, a class photo and a Bible, in a forgotten cupboard. The collection of documents all appeared to belong to one pupil, Louise Pikovsky. The teacher, Christine Lerch, tried, in vain, to find out more about Louise. Despite her failed attempts, she knew the documents were important and needed to be preserved. Shortly before leaving the school to retire, she entrusted the school’s librarian with the precious trove.

Khalida was so touched by the letters that she decided to pick up the trail. “I found them very moving. I would think about Louise’s story when I saw the pupils I work with now. It could have been anyone at this school,” she says. “The library was built as an extension on top of the roof terrace where Louise took gymnastics classes. She studied in the rooms I’ve been working in these last few years. The walls haven’t moved. Sometimes, it feels like they have a story to tell.”

Khalida heard about my interest in World War Two and contacted me for help with her research. Together, we decided to retrace Louise Pikovsky’s footsteps.

The first days of our investigation were very fruitful. On the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial website, we found a note left in 2000 by Jacques Kohn, Françoise and Danièle’s brother. He wrote that his uncle, aunt and cousins were killed during the Holocaust. Jacques Kohn has since died but his contact details, included in the note, took us to his sisters in Jerusalem.

The Pikovsky family is also indexed on the website of the Shoah Memorial in Paris. Abraham, the father, Barbe Brunette, the mother, and their four children were deported to Auschwitz on the same day: February 3, 1944. All six family members were part of the 67th convoy from Drancy, a northeastern suburb of Paris where the Nazis had set up an internment camp. They were assigned individual numbers from 12194 to 12199. Their convoy was one of the last to leave before the liberation of Paris in August 1944.

Names and numbers were useful starting points for us, but administrative information left behind by the Nazis was not going to be enough to tell Louise’s story. To find out who she was, we needed to explore her letters.