Video: the investigation

Video: the investigation

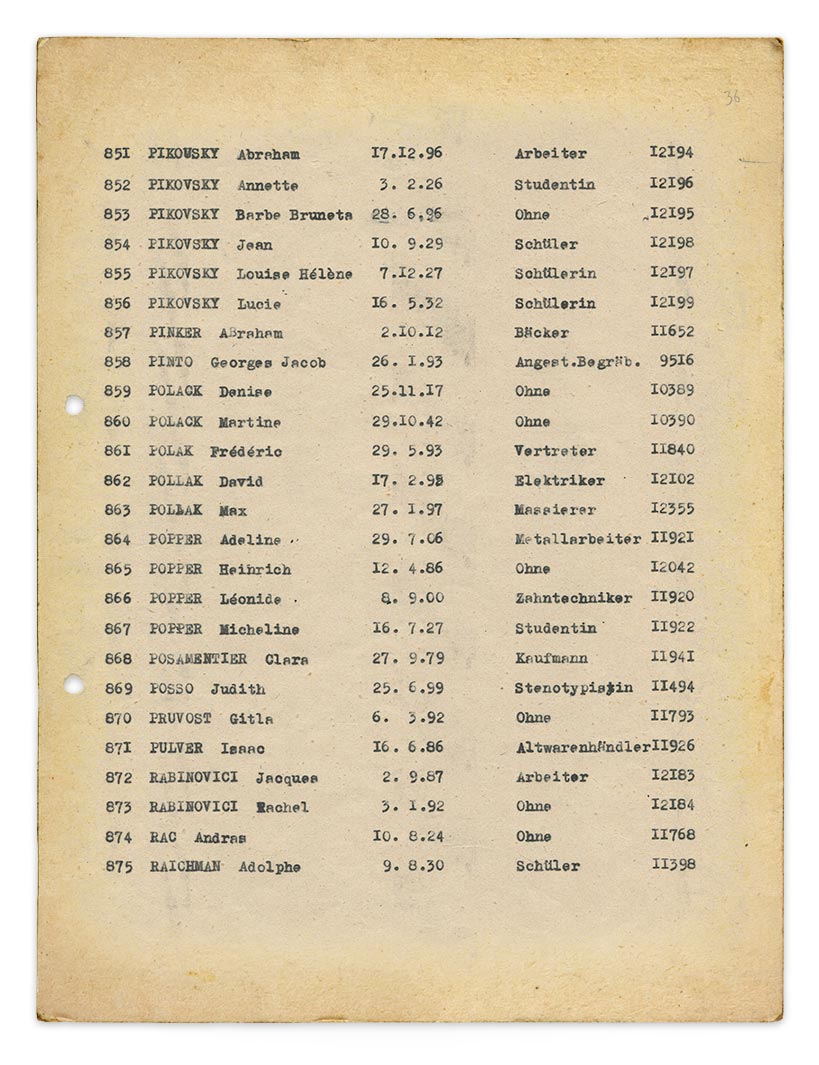

An individual record card was produced for each member of the Pikovsky family once they arrived in Drancy. The cards are kept in a locked glass cabinet at the Shoah Memorial in Paris alongside tens of thousands of others. Known collectively as the “Jewish file”, the precious records are proof of the deportation process in Nazi-occupied France.

Digitalised copies are available for consultation at the National Archives. Archivist Caroline Piketty offered to show us the Pikovskys’ record cards. Abraham’s card specifies his nationality, “Russian”, his profession, “manual worker”, and his address, 50 rue Georges Sorel. On Louise’s card she is described as a “schoolgirl”. The letter “B” is visible in large blue writing on all six Pikovsky record cards. “That means they were selected to be deported rapidly,” Piketty explained. “For the Germans, a family with children meant more complications.” There is also a receipt, dated January 22, 1944, which shows Abraham left 885 francs, roughly the equivalent of 156 euros today, with the German authorities when he entered the camp.

What happened to the rest of their belongings? To try to find out, Piketty showed us how to explore the National Archives. We were faced with a maze of shelves containing more than 600 boxes of documents compiled by the police during World War Two. “It’s always instructive”, said the archivist, who has spent years researching the expropriation of Jews during the war. “You’d think we become indifferent to the subject after spending so much time wandering around these archives, but fortunately we don’t.” There were thousands of documents detailing the confiscation of Jewish belongings, including bank statements of blocked accounts. But we found nothing with the Pikovsky’s name on it. “The father of the family was a taxi driver. He didn’t have a business in his name. And he didn’t own the apartment either. So it’s not easy finding something,” said Piketty. “In terms of their belongings, their apartment would have been sealed after their arrest. The Germans would have come with a removal van to take everything away. The concierge may also have helped themselves before then. There are all sorts of possible scenarios.” The Pikovskys were not well-off and did not own any works of art. Their modest possessions would have been taken to German depots where objects stolen from Jewish-owned apartments were divided up, packed on to trains and sent across the Rhine River, disappearing without a trace.

Louise and her family were separated when they arrived at the internment camp in Drancy. A police register shows Abraham and Jean were put in room 8.4 with other men and boys. Barbe Brunette and her three girls ended up in room 10.3. We consulted the camp’s layout at the Drancy Memorial Museum, part of the Shoah Memorial, and discovered the first number corresponded to a stairway. We were soon able to work out exactly where the Pikovksys were imprisoned.

The museum is right opposite a 1930s housing estate that was used for the internment camp. The Cité de la Muette estate was requisitioned by the Germans in 1940, not long after it was built. They first used it to hold French and British prisoners, before turning it into an internment camp. Between 1941 and 1944, more than 80,000 Jews were detained there. The Cité de la Muette went back to its original purpose as a social housing estate at the end of the war. Seven decades later, very little has changed. Louise and her family were locked up in what is now social housing reserved for deprived individuals and families. Residents live in the same rooms in which Jews were imprisoned.

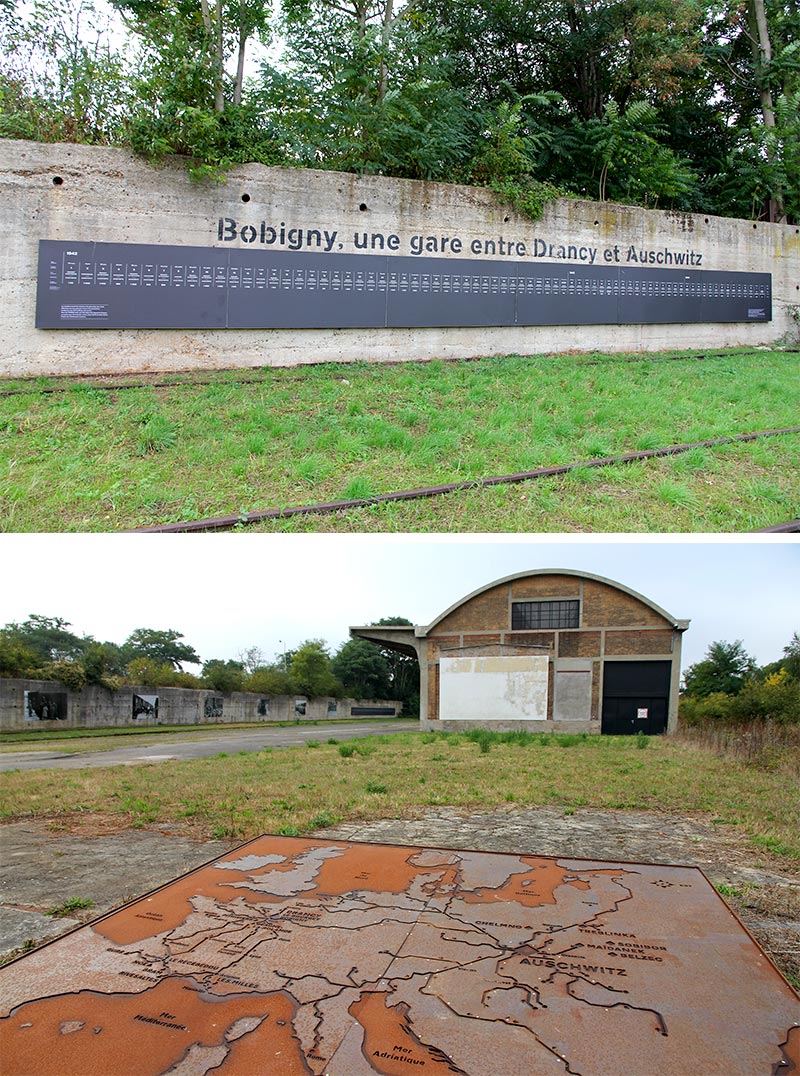

A monument and an old train wagon have been placed at the main entrance to the estate in remembrance of those who were deported. But the wagon is out-of-place, as the trains did not leave Drancy for the death camps. The night before being deported, prisoners were gathered in a designated part of the camp. The next morning they were driven in buses to the train station in Bobigny, two kilometres away. The Pikovskys did not stay long in Drancy. They entered the camp on January 22 and were placed in Convoy no.67. It left Bobigny less than two weeks after their arrival, on February 3, 1944.

On that fateful day, February 3, 1944, Louise’s older sister Annette turned 18. Her last birthday was spent alongside 1,213 other people, 184 of them children, who were forced to board Convoy no. 67. Among them was teenager Léa Schwartzmann. Originally from Tinqueux near Reims, she was arrested a few days earlier with her parents and 11 siblings. When we met her, the 91-year-old said she did not recall meeting the Pikovsky family, but she remembered every detail of the horrific journey to Auschwitz.

Sitting in her Parisian apartment, she described the unimaginable suffering she went through. Up until the last minute, she and her family thought they were going through a bad dream. “We weren’t all that scared because we thought the Germans had made a mistake and that we would be able to leave Drancy. But the night before, when we were called, we realised it was over for us. We’d fallen into a trap,” she recalled. The next day, the deportees of Convoy no. 67 were driven by bus to Bobigny train station. “It was really hard boarding the train. We could hear ‘schnell’ [fast, in German] being shouted. We had to leave behind a whole load of clothes. They used truncheons. It was really aggressive. I was scared of the big dogs, but we had to get on board. Already we were being stripped of our identity. It was terrible for a young girl of my age. (…) Once we got inside the train, the SS did a little speech telling us if anyone tried to save themselves, everyone would get shot.” But the worst was yet to come. The conditions inside the overcrowded and windowless cattle wagons were inhumane, with the deportees exposed to thirst, hunger, an unbearable stench and a total lack of intimacy: “When we needed to go to the toilet, someone would cover us with a blanket. It was an awful journey.”

The entire Schwartzmann family was in the same wagon, but there was little conversation during the journey. “My mother did not say a word to us. We weren’t exactly scared, but we did feel anxious. We were clueless. What were they going to do with us? We were worried about being separated,” Léa recalled. After three days and three nights, the doors of the wagon finally opened: “It was an awful thing because two or three people had already died. When we got off the train, we had to move fast without paying attention to others around us.”

It was as if this elegant elderly lady, sitting comfortably in her living room, was in another place as she recollected the ordeal she went through. She was back at Auschwitz, in Poland, where the train came to a stop. She was reliving every moment of what happened when she arrived. “They made us get off with such brutality. That’s when I understood what the SS were capable of. They were monsters,” she said. In the scramble, the young girl soon lost sight of her father. Her mother just had time to say “see you tonight”.

Along with her sister Suzanne, Léa had been selected to join the line of people on the right. The rest of the family was directed towards the left: “We saw the trucks arrive. They took the sick and the children. My sister and I said to each other they couldn’t possibly be so cruel. You see how organised it was!” The two siblings were taken to the women’s camp at Birkenau, part of the sprawling Auschwitz complex. There they were immediately shaved and tattooed. A few hours later, reality hit: “Some young French women asked us where we were from. They laughed nervously when we asked ‘Where are our parents?’ Some Polish Jews who could speak French replied: ‘Don’t you understand? Here at Birkenau they’re gassing people!’ My sister and I looked at each other and that was the only time we cried.”

Léa’s piercing blue eyes reveal the extraordinary resolve and defiance that saw her through the horror of Auschwitz. She also credits “luck and faith: the luck that meant I wasn’t selected for the gas chambers, and the faith that I clung to for my family, which gave me strength and courage.” Was Louise Pikovsky also chosen for the labour camps, or was she sent straight to the gas chambers? Nothing in the archives at Auschwitz suggests she survived the first selection process upon arrival. There is not a single trace of her presence, other than the list of deportees on Convoy no. 67. Out of the 1,214 people on board, only 166 men and 49 women were sent to the labour camps. The 985 others were immediately gassed. Why was the schoolgirl from Jean de La Fontaine not chosen when Léa Schwartzmann was? They were only two years apart. “Why me?” Léa often wonders. “My younger sister was 16 and she was bigger and stronger than me, but she was gassed straightaway and I wasn’t.”

According to an official French decree dated March 5, 2015, Louise Pikovsky died on February 8, 1944, at Auschwitz. But there is no material evidence to back up the date. The French state simply counted five days after the convoy’s departure from Bobigny in order to establish an administrative date of decease.

Léa Schwartzmann managed to survive both Auschwitz and the so-called “death marches” that followed, when the camp’s surviving population was forcibly evacuated towards Germany, as Soviet forces advanced from the east. She and her sister were eventually freed from Ravensbrück concentration camp in April 1945. Delicately, she lifted her sleeve to show us the prisoner number tattooed on her arm. Her persecutors left an indelible mark on her skin, but also on her spirit. “It’s awful living with the memory of what happened at Auschwitz. No one can get rid of that,” she said. “It’s difficult to make people understand what the Holocaust was. It was beyond anything else. It was hell. I am still at Auschwitz and Birkenau. It’s impossible to escape.”