The trial

Louis’ parents hadn’t heard from their son since July 1944. Letters in his file at the Service historique de la défense show their anguish. In 1945, his mother wrote to a research organisation: “Please tell me what to do, out of pity for a poor mother who’s suffering, who’s constantly waiting for news of her dear child – please tell me what to do. […] I’m a mum who’s really suffering; every day I’m waiting to find out if he is ok. The last we heard of him, he was seriously ill. Another inmate who came back to France said he was ailing and had to wear a cast.”

Louis’s parents were worried that his asthma might have caused him to die. They managed to glean some snippets of information from survivors, here and there. His cousin Anne Toucanne remembered a letter they received: “Someone told them Louis had been badly beaten with a rifle butt.”

In 1946, Claude Bottiau, a cartoonist from Morbihan and a survivor of Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen – whom Louis knew from his time in the Vannes prison – provided new testimony: Louis was in the infirmary on April 26, 1945, four days after the Soviets liberated the camp. They never received any further news of him.

For lack of any new information, Louis was officially declared dead in 1947, with the record stating that he “died for France” in Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen on April 26, 1945.

Louis’ parents never gave up hope that he would come back home. In September 1955, local newspaper La Liberté du Morbihan wrote that they had recently got a strange letter from a German – a former inmate at Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen. It claimed that Louis was still alive, suggesting that he was detained in the USSR. But it turned out to be fraudulent: The author was a shady character who intended to make money from his claim.

The bereaved parents turned to the Red Cross for information. They even consulted fortune tellers – such was their desperation. “My aunt lost her mind, really – she was just so shaken up by it all,” Toucanne said.

Marie-Anne Séché died two years after they received the fraudulent letter from Germany, in 1957. Her husband died ten years later. They never found out exactly what happened to their son. Did he succumb – robbed of his strength by the camp’s incessant punishing horror – just after hope arrived when the Red Army liberated it? That is the most likely hypothesis, though the exact circumstances of his death remain a mystery.

Lisette is also mentioned in the article published by La Liberté du Morbihan in September 1955. The journalists visited her widowed mother: “She said her last memory of her unfortunate young daughter was a triple photo taken from a file at that infamous place Auschwitz, where everyone was stripped of all individuality and turned into nothing more than a number among numbers – in her case, 31,825.”

Unlike Louis’ parents, Suzanne Moru knew that there was no hope of seeing her child again. “When France was liberated in 1945, two of my daughter’s fellow inmates – Mrs Marie-Elisa Nordmann and Miss Marcelle Mourot – informed me of her death at Auschwitz in March 1943,” she told the gendarmes.

An investigation was opened into the circumstances of Lisette’s and Louis’ arrest. French authorities issued an arrest warrant for the German customs officer Jean Hirsch – whose real first name was Hans. He was temporarily detained in a prison camp in Germany – but never extradited, as archives from France’s military justice system revealed.

But proceedings went forward against three women: Mademoiselle G, Lisette’s colleague; her mother, Madame G, and another woman working at customs in Port-Louis, identified as Madame B. They were accused of having “maintained ties with agents of the German enemy during the war, by reporting to the German authorities actions by French people, which were likely to provoke reprisals against them”. They blamed each other under interrogation.

They went on trial in September 1945 in Rennes. Mademoiselle G was acquitted; Madame G and Madame B were found guilty and sentenced to three and two years in prison, respectively, and a lifelong status of “disgrace to the nation”.

A symbolic reunion

Marcelle Mourot, Lisette’s friend who had stayed with her at Auschwitz until she died, married a fellow deportee from Besançon soon after the war. Her husband, Jean Paratte, had been part of the same convoy as Louis, bound for Sachsenhausen. They went on to have two children together.

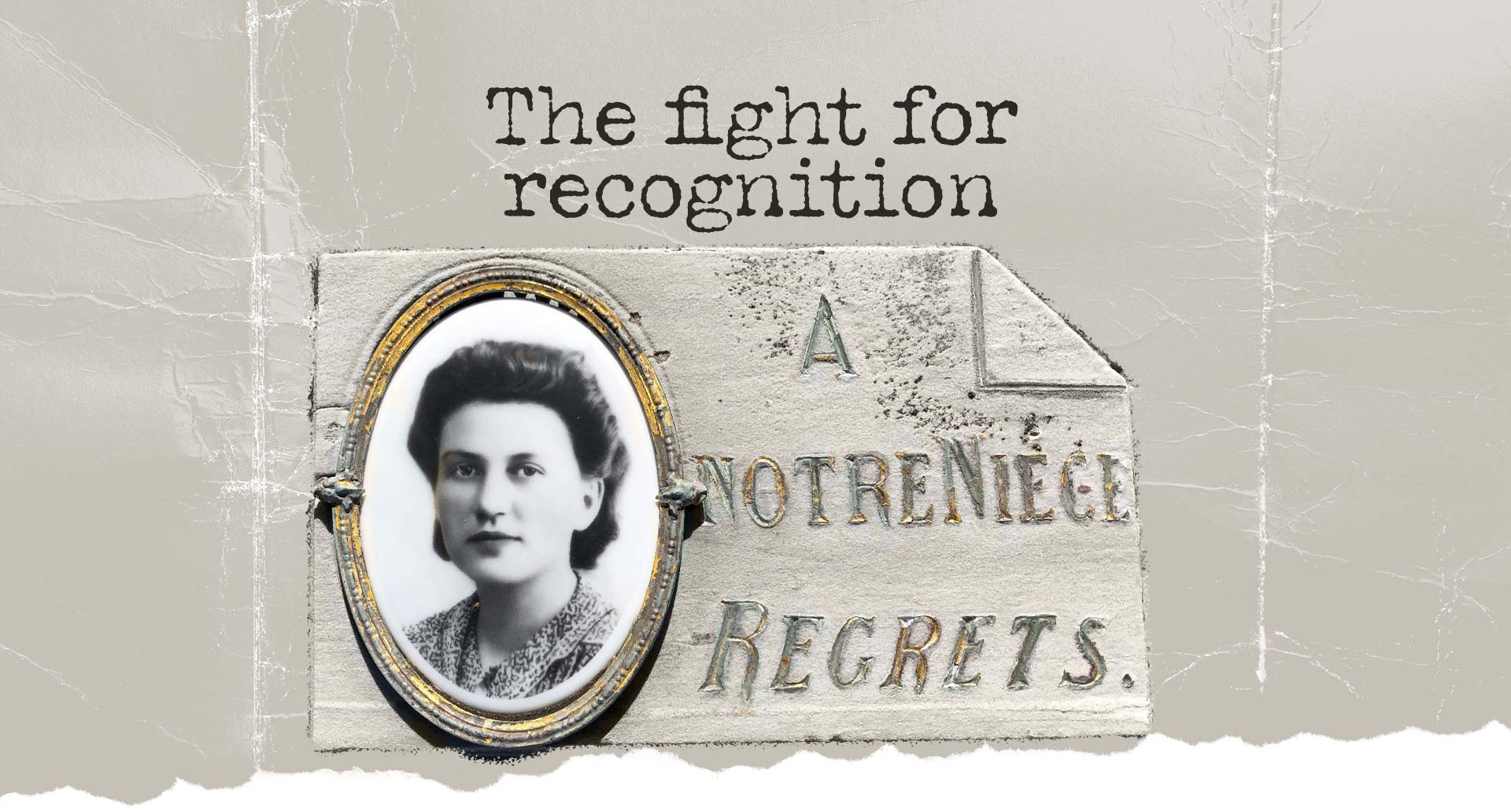

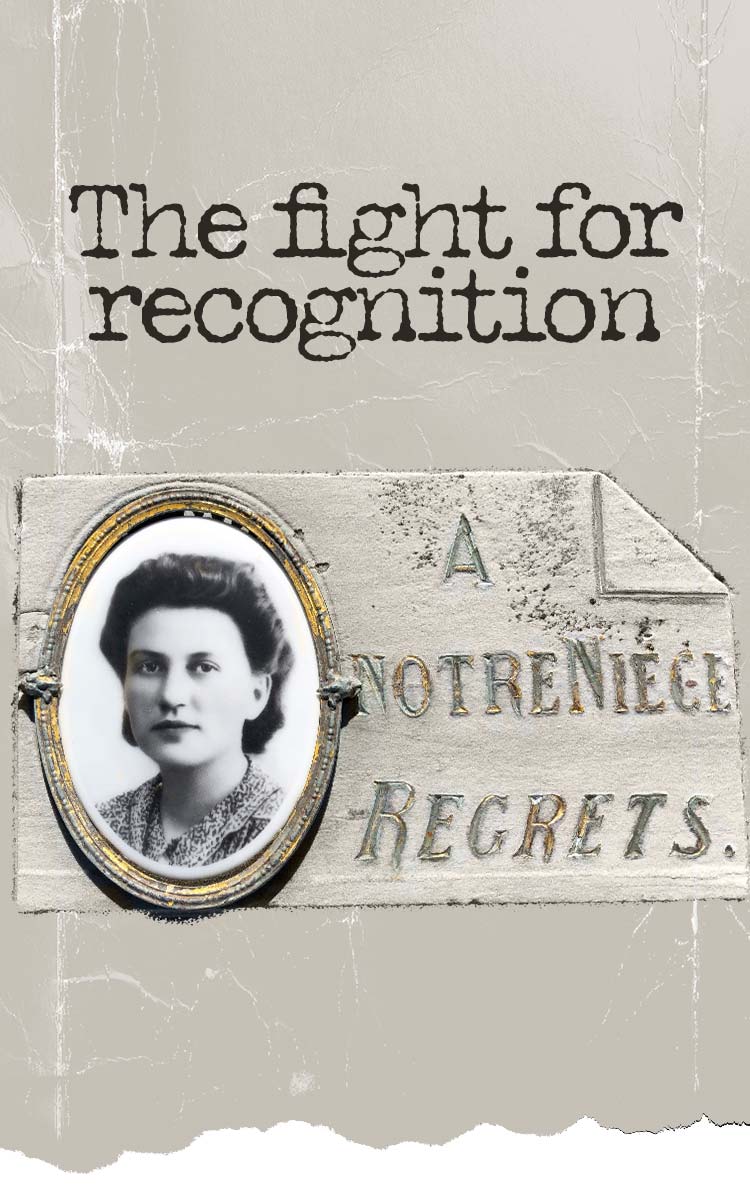

Though Lisette and Louis were apart throughout their deportation, the young couple were at least symbolically reunited when both their names were added to the Port-Louis war memorial. However, their hometown slowly forgot them. Only their families continued to cherish their memory.

It remains a delicate subject in the Breton seaside town, where relatives of the denouncers still live. Many people just don’t want to reawaken old memories, according to members of the local historical society, who helped me with my research. They invited me over for coffee, Breton pastries and a candid chat about the young couple's tragic fate. “The most shocking aspects of this case are the denunciations and the fact that they were so young,” said Soizick Le Pautremat, a linchpin of the group.

For several years the association has focused mainly on Resistance members shot in the citadel, which the German occupiers had made into a prison. On May 18, 1945 a mass grave was discovered containing the bodies of 69 Resistance members from across Morbihan, as well as the nearby counties of Finistère and Côtes-d’Armor. Since then there have been commemorative events every year. President Nicolas Sarkozy went along to show his respects in 2011.

The local historical society is committed to remembering this tragic episode – but it is also keen to honour the memories of other Port-Louisians killed during the Second World War. “We talk a lot about those who were killed at the citadel but there were other Resistance members from the local area who don’t get a lot of attention,” said Françoise Le Louër, head of the Centre d’animation historique du pays de Port-Louis. Consequently, the society decided along with the local council to inaugurate a new plaque in honour of six Port-Louisian Resistance members who were shot dead and six who were sent off to die in concentration camps. It was placed in the vicinity of the citadel, to coincide with France’s national day of remembrance for the victims of deportation, on April 25, 2021.

The names of Lisette and her partner are among the 12. “She’s the only one who was sent to Auschwitz – she died there; and we’ve got to remember what she did as part of the Resistance, with that youthful innocence and cheek,” Le Pautremat said. The local council also decided to name a street after Lisette Moru in 2018.

More than 75 years after she was arrested and deported, her memory is finally being honoured. Her niece Roselyne Le Labousse couldn’t be happier: “I’m not looking for accolades – just acknowledgement. Not just for Lisette, but for all the young people during the war who risked their lives, who decided to resist the Occupation when they had all their lives ahead of them and the potential consequences were monstrous.”

The 49 survivors of the “31,000 convoy” have carried that memory for decades, before passing on the baton. Their message is perhaps best captured in the words of Lisette’s companion Charlotte Delbo and her poem “Prière aux Vivants” (“Prayer to the Living”):