A haunting image

There’s laughter in her face. There’s something bold in her eyes. Her smile is a bit of a smirk; it has a rebellious quality. If it weren’t for the shaved hair, the number on the chest and the prison outfit – which scream Auschwitz – it looks like it could be any teenager’s photo ID.

I was astonished to stumble upon this photo in 2019 during my research on the French Resistance in Brittany. I couldn’t get over it. Why would she be smiling like that at Auschwitz? Who was this young woman? The look on her face stayed with me wherever I went. I was determined to find out who was behind this striking look and the dreadful anonymity of her camp number, 31,825.

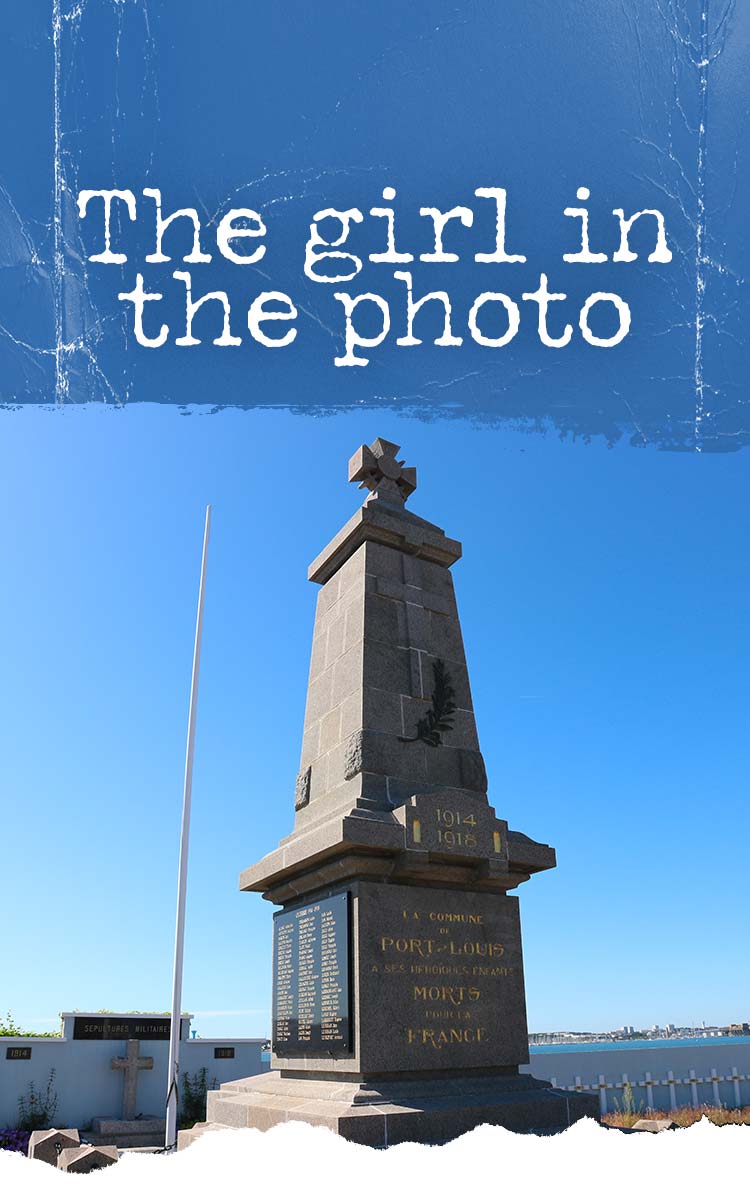

There wasn’t much information about her on the Internet. Lisette left few marks except for that photo. Articles for commemorative events briefly refer to her as a “passive” member of the Resistance, arrested during the Occupation for putting flowers on the war memorial in her native town Port-Louis: a harsh fate for a relatively insignificant act. This only fed my interest in Lisette’s story.

Several articles mentioned someone called Jeannine Barré, who was active in keeping the memory of Lisette alive. I contacted her. She was delighted by my interest in the girl in the photo, and we scheduled a meeting for a few weeks later.

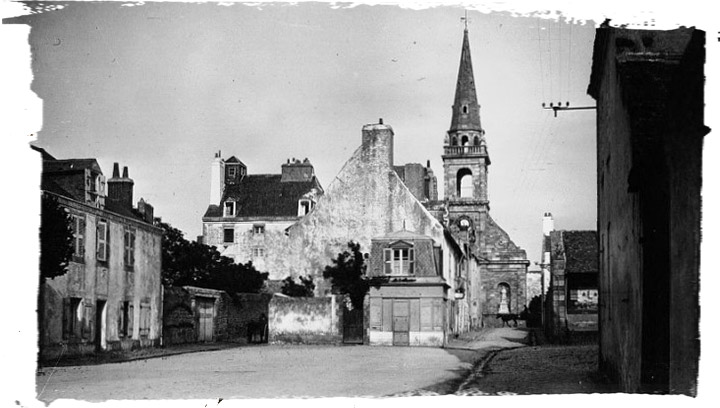

I arrived in Port-Louis on a beautiful day in August. Just over 2,500 people live in the town, on a small peninsula jutting into the Atlantic on Brittany’s southern coast. The place owes its name to King Louis XIII, who made it a fortified settlement as part of France’s defences against the English, Spanish and Dutch during his reign in the first half of the seventeenth century. Now a tourist spot, it hosts an exquisitely preserved citadel and ramparts from that era.

Barré lives in Port-Louis’s historic centre – in a small stone house with a garden, where she is spending her retirement. She comes from the Paris region, but has lived on the Breton coast for 35 years. She considers herself an adopted Port-Louisian, and has served the town as a local councillor.

The 86-year-old Barré is the local representative of the Fédération nationale des déportés et internés, résistants et patriotes (National Federation of Deportees, Camp Inmates and Patriots). “When I moved to Port-Louis, I soon told people that my brother François, a communist, was killed at Auschwitz. So I started making speeches at remembrance ceremonies,” she said.

She proudly showed me the mementos she had collected over the years, displayed on her living room table. “When I was talking to people here about the war, I learned that little Moru had also been deported to Auschwitz. Her parents lived near to me, so I went round to their house and asked them some questions.”

Barré felt a great deal of sympathy for them. They had been through the same tragedy: seeing a loved one deported and never returned. “They didn’t tell me much – just that she’d been arrested for leaving a bouquet of flowers at the Port-Louis war monument,” she recounted. It was on July 14, 1942 – Bastille Day – at the town’s cemetery. A friend had accompanied her. “They were summoned to the local German military headquarters and never came back,” Barré said. Lisette’s parents said that someone had denounced them to the Nazi occupiers.

Barré sensed a kind of embarrassed evasiveness in the town when she tried to dig deeper into Lisette’s story. Few Port-Louisians wanted to bring up the subject. People made it clear to Barré that they thought she should pay no attention to the matter. Nothing was done to honour Lisette’s memory; bad rumours about her circulated. “I found it shameful,” Barré said. “I didn’t understand. I wanted people to talk about this. Maybe she hadn’t done all that much – but she was the only one who had at least done something.”

Through sheer tenacity, Barré finally got the local youth centre to be dedicated to Lisette’s memory in 2008. But the circumstances of her arrest remained unclear. “I didn’t try to find out who denounced Lisette; her parents knew but they didn’t tell me,” Barré said.

“I wish you could look into this,” she told me. “I’d love to find out the truth before I die. If she was sent off to Auschwitz just for putting a bunch of flowers on the war memorial – I mean, that’s just mind-boggling!”

A rebellious temperament

Before I left her house on that sunny day in August 2019, Barré gave me the contact details of Roselyne Le Labousse, Lisette’s niece and the last closely related member of her family. Le Labousse also lives in Port-Louis; I rang her up and she agreed to speak to me, happy to talk about her aunt. She had already prepared some documents for me by the time I went round to her house near the sea.

Le Labousse is the memory of the Moru family. She has kept all their photos. She peered closely – with great tenderness – at a photo of Lisette in a dress for the Sacrament of the Eucharist. Le Labousse didn’t know her, but she heard about her often. “Lisette was a very strong person,” she said, remembering what her father had said. “Nothing frightened her.”

Tears started gathering in her eyes: “Talking about this brings so many memories flooding back to me. Right now I can just see my father crying.”

Le Labousse outlined the family tree. Marie-Louise Pierrette Moru, known as Lisette, was born on July 27, 1925. Her father, Joseph Moru, was 22 at the time and worked in the shipyard in nearby Lorient. Her mother, Suzanne Gahinet, was 24; she was a fish trader. Lisette was the eldest of three children; her brother Louis was Roselyne’s father.

Lisette in her dress for the Sacrament of the Eucharist (right). © Personal archives of Roselyne Le Labousse

Lisette grew up in a loving family. As a little girl she was known for her cheerfulness and her rich sense of humour. “She was laughing, mischievous, she had a hell of a temper. She looked a bit sly a lot of the time; maybe that’s what brought about her downfall,” Le Labousse said – painting a picture of Lisette that matches her look in the photo from Auschwitz.

After leaving school, Lisette got an official qualification to work as a seamstress. “She was intelligent; this kind of diploma was rare at the time.” But it was the start of the war; there wasn’t much demand and so there wasn’t much work. She was finally hired to work at the Breuzin-Delassus canning factory in Port-Louis. Sardines were the town’s main source of jobs at the time.

A rebel at heart, Lisette couldn’t stand the Occupation. Had her father spoken to her about Joseph Marie Moru, her grandfather who was killed on October 3, 1915, during the Great War? In any case, Lisette was incensed by the Nazis’ presence. She wore a Cross of Lorraine – the symbol of Charles de Gaulle’s Free France – under her jacket collar. “She’d take any opportunity she could to thumb her nose behind a German soldier’s back – she wasn’t shy; she’d do it in full view of everyone,” Le Labousse said.

With a few friends, Lisette became part of the Resistance – distributing anti-Nazi leaflets and keeping track of the occupiers’ movements. She joined the Nemrod intelligence network set up by Honoré d’Estienne d’Orves, a member of the Free French Forces who landed clandestinely on the Breton coast in December 1940, Le Labousse said.

Lisette joined this group thanks to Pierre Tual, a doctor from Port-Louis appointed by Estienne d’Orves as the head of its unit in the local area. “She worked for him, carrying messages,” Le Labousse remembered. Tual’s mission was to monitor the area around the citadel, then occupied by the Germans, who had chosen this strategic location to set up their command post for this part of the seafront. They had set up a bunker, complete with firing slots in the wall.

Le Labousse had heard about the flowers at the war memorial. But she had another version of the story: “It didn’t happen at the cemetery. A Royal Air Force pilot was shot down in the neighbouring town of Gâvres. Lisette went right across Port-Louis with her flowers and placed them where his plane crashed.”

She also knew the story about Lisette being denounced. The plaque in homage to her at the family grave acknowledges it: “To Marie-Louise Moru, who died for France at Auschwitz on 24/04/43, aged 17 and a half, denounced by two French women on 08/12/42.”

But La Labousse preferred not to dwell on the subject. “People are still traumatised by that period,” she said. “I know about a lot that went on amongst residents of this town during the war – but I keep it to myself. I know that two women denounced Lisette. But my parents always taught me to forgive. That’s what they did.”

Le Labousse didn’t want to stir up old resentments. But she was delighted that I was taking an interest in her aunt. She gave me carte blanche to carry out my research: “At least, this way, everything will be settled,” she said.