The women of Romainville

I found an old red notebook, stained with ink, in the Morbihan county archives. This is the prison register for Vannes, a major town in the area. The names and ages Louis Séché, 18, and Lisette Moru, 17, were inscribed in red ink with the words “German authority” on December 8, 1942. The two Port-Louisians left ten days later, on December 18, when they were sent to the Paris region.

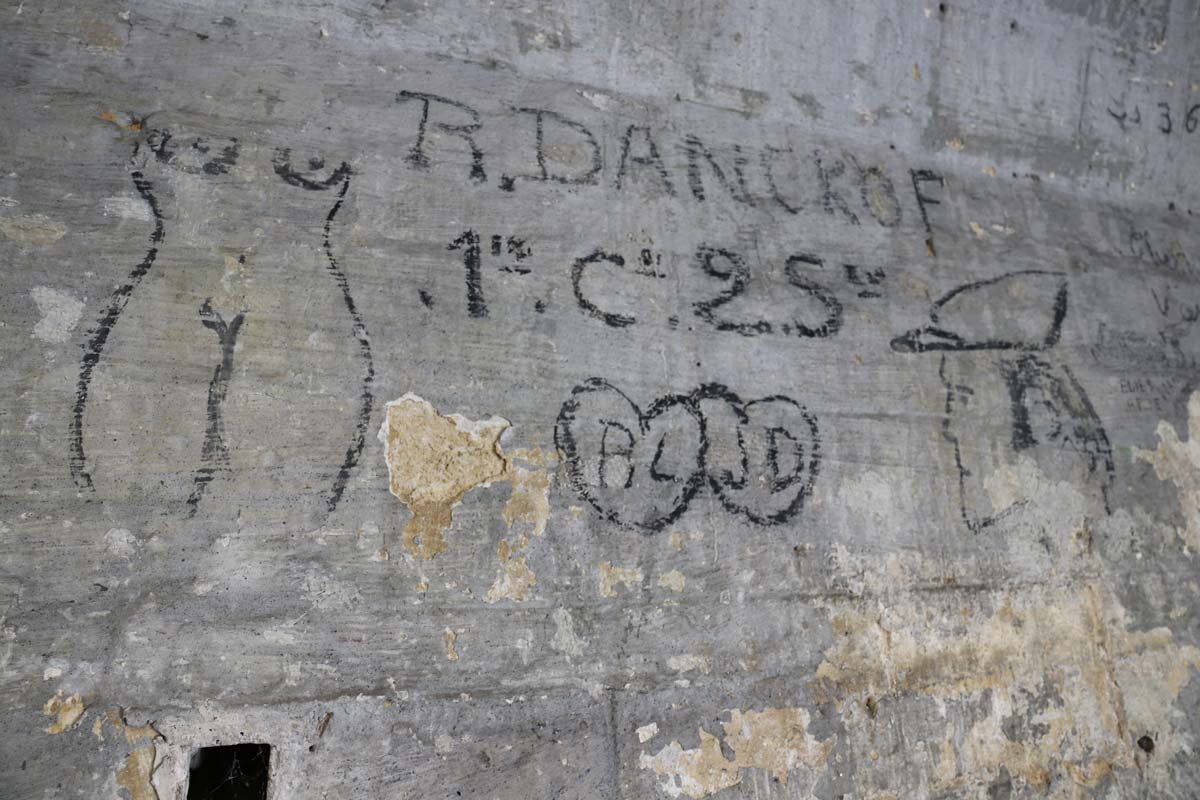

Louis was sent to the Royallieu prison in the rural Oise area to the north of the French capital; Lisette was detained at the fort of Romainville, to the city’s northeast. The Wehrmacht directly administered both prisons. Their purpose was to imprison “active enemies of the Reich”, arrested for actions against Nazi Germany and its army or for “threatening the maintenance of order and security”.

Lisette was registered with the number 1,332. According to the fort’s records, she entered the prison the same day as two other women: Marcelle Fuglesang and Anna Jacquat, two Resistance members from the town of Charleville near France’s Belgian border, who had been part of an escape network for prisoners and British airmen.

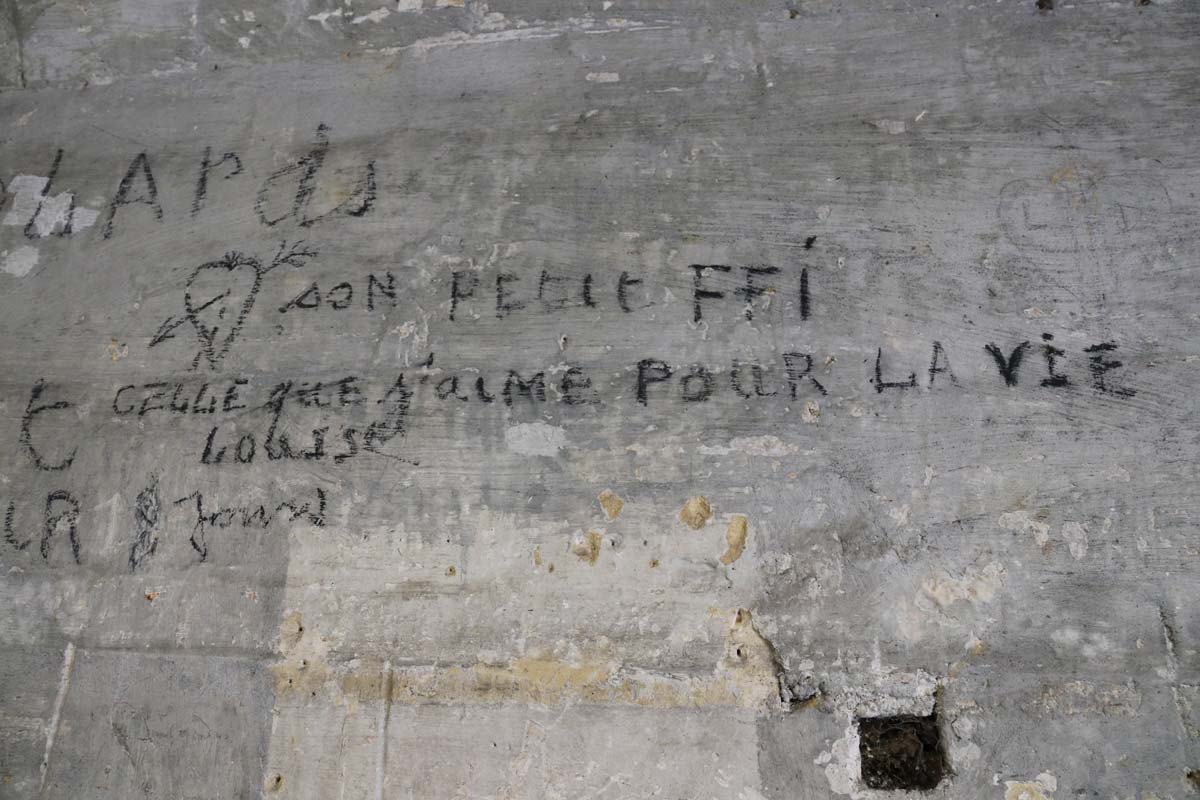

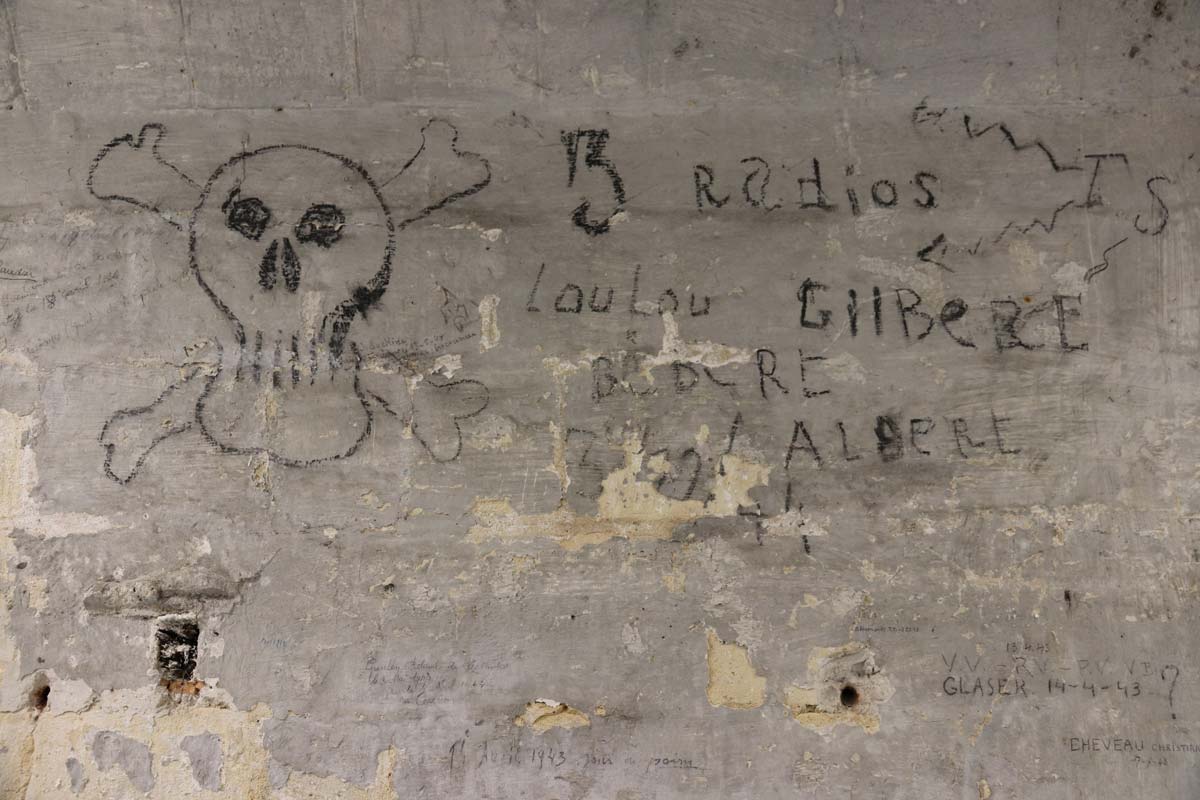

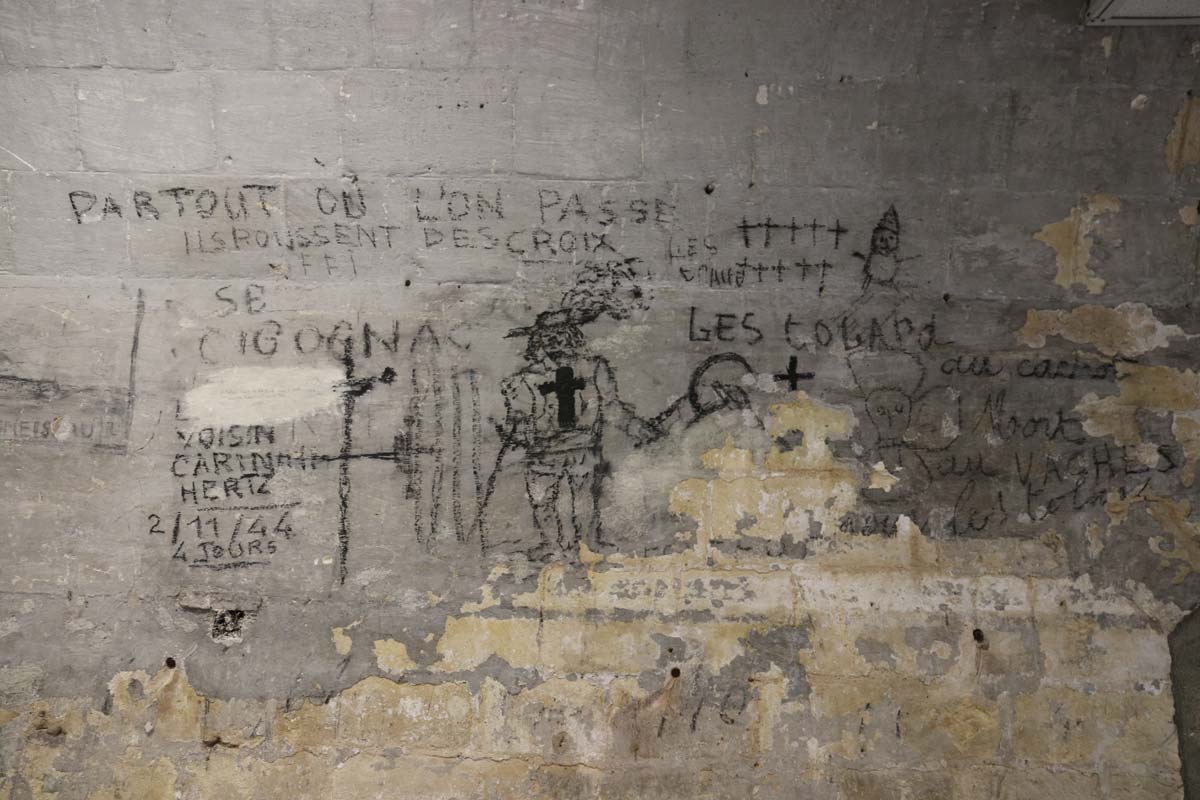

The day before, a Breton called Rosa Floch (known as Rosie) was transferred to Romainville. She was the same age as Lisette, and had been arrested for a trivial reason: a German military police officer had found her graffitiing the wall of a school in Brest with the letter “V” for victory.

Hundreds of other women were detained in the fort. Many had arrived in August and October 1942. A few, like Floch, weren’t part of any organised network. But the vast majority were communists. Some of these Resistance members went down in history. They include Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier, a journalist for the communist newspaper L’Humanité (which was published clandestinely during the war) and a liaison between the French Communist Party’s leadership and the various branches of the Resistance, who testified at the Nuremberg Trials. Others included Danielle Casanova, a dental surgeon and editor of clandestine publication La Voix des Femmes (“The Voice of Women”), and Charlotte Delbo, who later wrote a well-known book, Le Convoi du 24 Janvier (“The January 24 Convoy”), paying homage to her fellow Resistance members.

Some of them were widowed by the time Lisette arrived. Their husbands had been put on the September 21, 1942 hostage list and shot, as French historian Thomas Fontaine explained in his book Les Oubliés de Romainville (“The Forgotten of Romainville”). Since the summer of 1942, the Nazis had been using Romainville to gather hostages for execution at the Mont-Valérien, a fort to the west of Paris. In response to the assassination in the Paris metro of a midshipman in the German Navy in August 1941, the occupiers had decreed that in the event of another such attack, “a number of hostages corresponding to its seriousness will be shot in retaliation”.

Lisette managed to send her family a letter from Romainville, in which she recounts her day-to-day existence in the prison. Her niece Roselyne treasures it like a relic. Most of the words scribbled in pencil have now faded, but a few stand out. After addressing her family with “Dear all”, Lisette wrote that she was entitled to “two packages once every two weeks” and that she was allowed to “write several letters or two cards”. She asked her parents for bread, a cake, a blouse, shirts, socks, a clothes brush, a saucepan, cologne and cigarettes (which she could use for barter with her fellow inmates).

She stressed the sense of solidarity amongst the prisoners: “Everyone receives packages and they share their contents with me.” The inmates didn’t get enough food and so they set up an informal system in which they pooled the contents of packages to improve their lot.

“You must be worried,” Lisette wrote, before trying to reassure her family: “The news I’m recounting is very good and I hope everything is going well at home.” She concludes with an ardent statement of affection: “My dear little mum, my darling little daddy, I’m sending you kisses, and the same for my little grandma whom I love so much.”

Lisette wasn’t at the fort for long. On January 23, 1943, a month after her arrival, she was transferred to Royallieu along with 121 fellow inmates. There they found 100 other women who had been transferred from Romainville the previous day, as well as eight prisoners from other detention camps. The following day, the 230 women were taken to Compiègne train station in the same area. More than 1,500 men were already there, crammed into wagons. Lisette’s boyfriend Louis Séché was one of them.

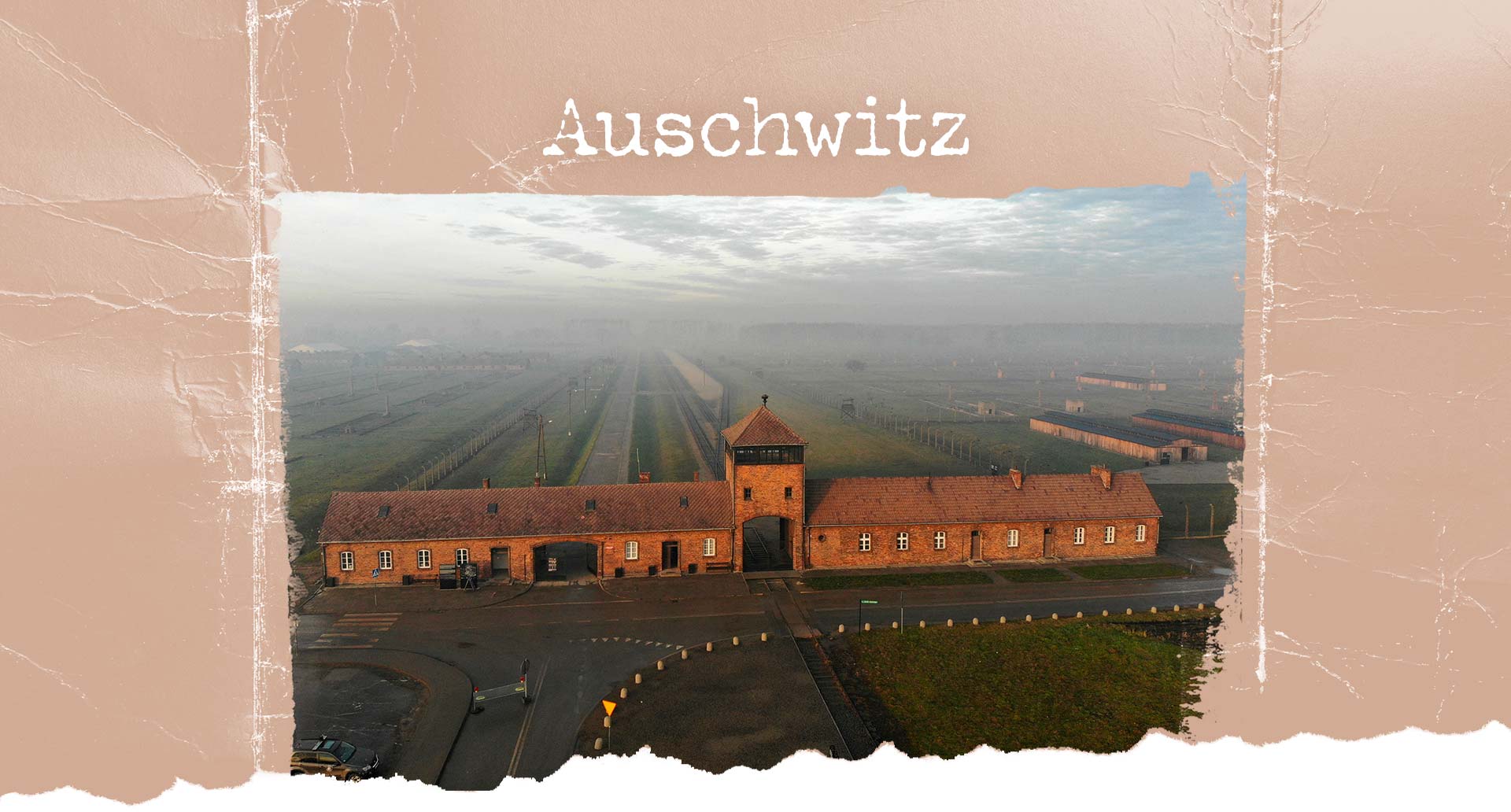

The train set off, heading for Germany. When it arrived at Halle station in the east of the country, the train’s wagons were divided into two. Those transporting the men headed for Sachsenhausen concentration camp, 30 kilometres north of Berlin. The others, containing the women, went to Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland.

Auschwitz-Birkenau, hell on earth

The women arrived at their destination on the evening of January 26. They were left in the wagons overnight. When the doors opened the next morning, they entered hell. Charlotte Delbo recounted it in Le Convoi du 24 Janvier: “Cries, howls, unfathomable orders, dogs, SS, machine guns, weapons clinking. No train station, just the side of the track. Brutal cold. Where were we? We only found out two months later.”

The 230 women were taken on foot to Birkenau, also known as Auschwitz II. “Halfway through the trek we came across women wearing stripes, a long column of them,” Delbo continued. “The kapos [the prisoners responsible for supervising their fellow inmates in Nazi concentration camps] ordered them to let us pass. They were deathly pale; some even looked purple. We sensed a foul odour, one we were reluctant to attribute to them. It was like the smell of an unkept barn, of dirty cows.”

Many Resistance members held their heads high amid the horror – entering the camp singing, as proudly remembered in L’Exercice de Vivre (“The Exercise of Life”), a memoir by Simone Alizon, a young member of the Resistance, from Brittany and the same age as Lisette, who had been arrested in Rennes in March 1942. “Suddenly, gushing out of the anguish, a voice started singing the French national anthem, La Marseillaise. As soon as she started, everyone joined in. The song was interspersed with sobs. It was filled with defiance and despair – freedom’s last song in this place of death.”

The women were then directed to the shower. Their hair and pubic hair were shaved. They were tattooed on their left forearms with a registration number between 31,625 and 31,854 – that is why the group later came to be known as the “31,000 convoy”. Lisette got the number 31,825.

All personal items were confiscated. They were given prison clothing. Delbo remembered the disgust at these filthy rags: “The shirts, underwear and dresses had blood, pus and diarrhea stains. There were nits in the seams.” The women had to sew an “F” for “French” on a red triangle, showing that they were political prisoners. Their humanity was taken away from them, step by step.

Lisette’s was the only convoy sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau from France comprised of female Resistance members. All other convoys whose final destination was the Nazi extermination camp in Poland transported Jews, except for one convoy sent on July 6, 1942 containing some 1,170 members of the Resistance. All the other women in the Resistance who were deported were sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp or to prisons in Germany.

So why were Lisette and her fellow Romainville inmates sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau? “This is a very particular case,” said French historian Pierre-Emmanuel Dufayel, a member of the research team at the Fondation pour la mémoire de la déportation (the Foundation for the Memory of the Deportation). “The most plausible hypothesis is that the Nazis saw it as a reprisal against the Resistance, a change of approach after the policy of murdering large numbers of hostages decided upon in September 1942.”

The hostage policy proved to be counter-productive for the German occupiers in autumn 1942. It didn’t stop Resistance attacks on them – and carrying out mass executions hardly won the Nazis goodwill from the French public. In light of that, the occupying forces decided on another form of repression: deportation to concentration camps, where inmates could service the growing needs of the Third Reich’s war economy.

“Another significant thing about the ‘31,000 convoy’ is that more than half of the deportees were communists, including some who had been at the top of the political apparatus. That’s why they were sent to Auschwitz, which had a camp for female hostages,” Dufayel said.

During the first two weeks, the women of the “31,000 convoy” were placed in quarantine in Block 14. They were temporarily exempted from work – but were forced to stand for hours during endless roll calls. “We didn’t speak; the words would have frozen on our lips,” Delbo wrote. “The cold was such a shock to all the women standing still. In the night. In the cold. In the wind. We were standing still and it was ridiculous that we were still standing. Because what was the point of doing so? No one was asking this question. At the utmost limit of our strength, we stood.” But some women were already dying.

On February 3, the Resistance members were taken to Auschwitz I, the main concentration camp, to be photographed. It is there that the photo of Lisette was taken, with that rebellious smile.

“Any detainee entering the camp had to go through this formality,” Alizon wrote. “The camp administration offices functioned very efficiently. Some detainees deemed ‘prominent’ kept the records, under the SS’s watchful eye. Everything was recorded perfectly, except for the dates of death, which were just approximations. For the SS we were merely numbers.”

A week later, they were forced to run in front of medics and camp guards, who picked out the weakest. It was a nightmarish ordeal for Delbo: “The blows came raining down on our heads and necks. They were shouting ‘Faster! Faster!’ over and over again. […] I just ran. No one refused to conform to the absurdity. We ran. We ran.” After the punitive “race”, 14 women were sent to Block 25, the camp’s death house.

On February 12, Lisette and several other inmates were sent to Block 26, crammed in alongside Polish inmates. They had to join working groups called “Kommandos”. The first weeks were the hardest: There was a typhus epidemic raging in the camp, and the most fragile were sent to the gas chambers. Death was everywhere.

Christiane Borras, known as Cécile, described the pile of lifeless bodies in her memoir Cécile, Une 31,000 (“Cécile, One of the 31,000”): “At the beginning it’s terrible, but after a certain point, you’re dead tired and you know you’re going to die. You still have such a distance to cover, and the next day all over again. As long as you’re alive, they’ll make you trek through miles in the mud and the snow. And when you’re tired, and you smell that smell, by that point you’re no longer noticing that it’s the smell of the dead.”

Amid their ordeal, the Resistance members are soon aware of the sinister fate of the Jews deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where almost a million perished. “When the convoys of Jews got off the train, […] only young people and those fit for work entered the camp,” Delbo recounted. “The others were gassed immediately. But often the whole convoy went into the gas chamber.”

What happened to Lisette during her first weeks at the Nazi camp will probably never be known. According to survivors’ testimony, she succumbed quickly. She died at the end of March 1943, aged 17, in an area of the camp they called “Revier”, where the sick were crowded together without any hygienic measures or medication.

Marcelle Mourot, a young Resistance fighter from Besançon, who had arrived at Romainville a few days before Lisette, was by her side at Auschwitz-Birkenau during her last moments. “She was suffering from serious dysentery or diarrhea and she never got better,” she wrote in a letter to Lisette’s parents after the Liberation, a document kept by Roselyne Le Labousse. “She was thinking a lot about you during her last moments,” the letter continued – adding that Mourot felt “enormous sorrow” over the death of Lisette, her “only comrade” during her captivity.

“I would be very happy to be able to speak to you in person to tell you about the courage she showed,” Mourot wrote.

Three months after the “31,000 convoy” arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau, only 70 of the French deportees were still alive. The young Breton Rosa Floch – the one who drew the "V" for victory on the walls of Brest – also died at the "Revier" in March, as did Marcelle Fluglesang and Anna Jacquat, who arrived at the fort of Romainville the same day as Lisette.

By the end of the war, only 49 women out of the 230 in the “31,000 convoy” had survived Auschwitz-Birkenau; a death rate of 79 percent. “Overall, around one in five members of the French Resistance was killed – but in the case of this convoy sent to Auschwitz, it was the opposite: one in five returned,” Dufayel noted.

More than 600 kilometres away from Auschwitz, Louis survived for more than two years at Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Like Lisette, he was just a number – 58,178. After spending some time in quarantine, he was assigned to a “Kommando” unit. His daily life followed an unchanging routine: waking up between 3:30 am and 4:30 am, lining up for endless roll calls, working, lining up again, and then returning to overcrowded barracks. Lack of food, lack of sleep, lack of hygiene, backbreaking work, bullying and punishments were all part of the daily torment.

But Louis was able to keep up regular correspondence with his parents until the end of July 1944. He informed them that he was working as a warehouse clerk at an Ernst Heinkel aircraft factory. He was in the largest Kommando group at Sachsenhausen, which had between 6,000 and 7,000 detainees. Discipline was severe. Inmates were beaten for showing the slightest act of clumsiness.

“It’s very hard at Heinkel; it’s a hellish place and fatigue hollows out people’s faces,” Marcel Courandeau, who was deported on the same convoy as Louis on January 24, 1943, wrote in his memoir Ma Deportation (“My Deportation”). “There’s never enough food; your friends are getting weaker and weaker. In the evening you sink into your bed – stupefied, emptied of all energy, and you have to carry on like that until the exhaustion is complete; until the end of your shitty life.”