The RAF trail

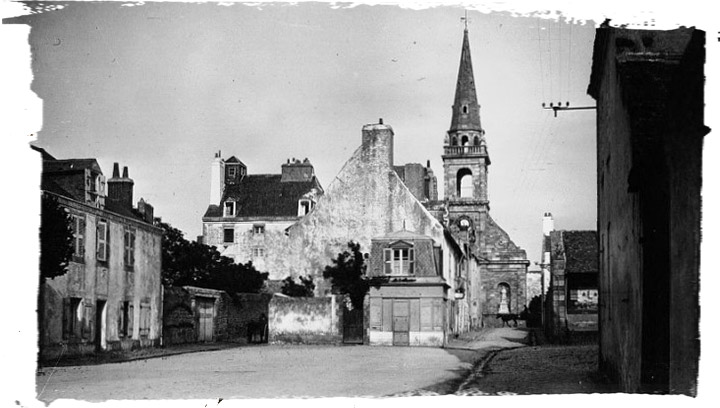

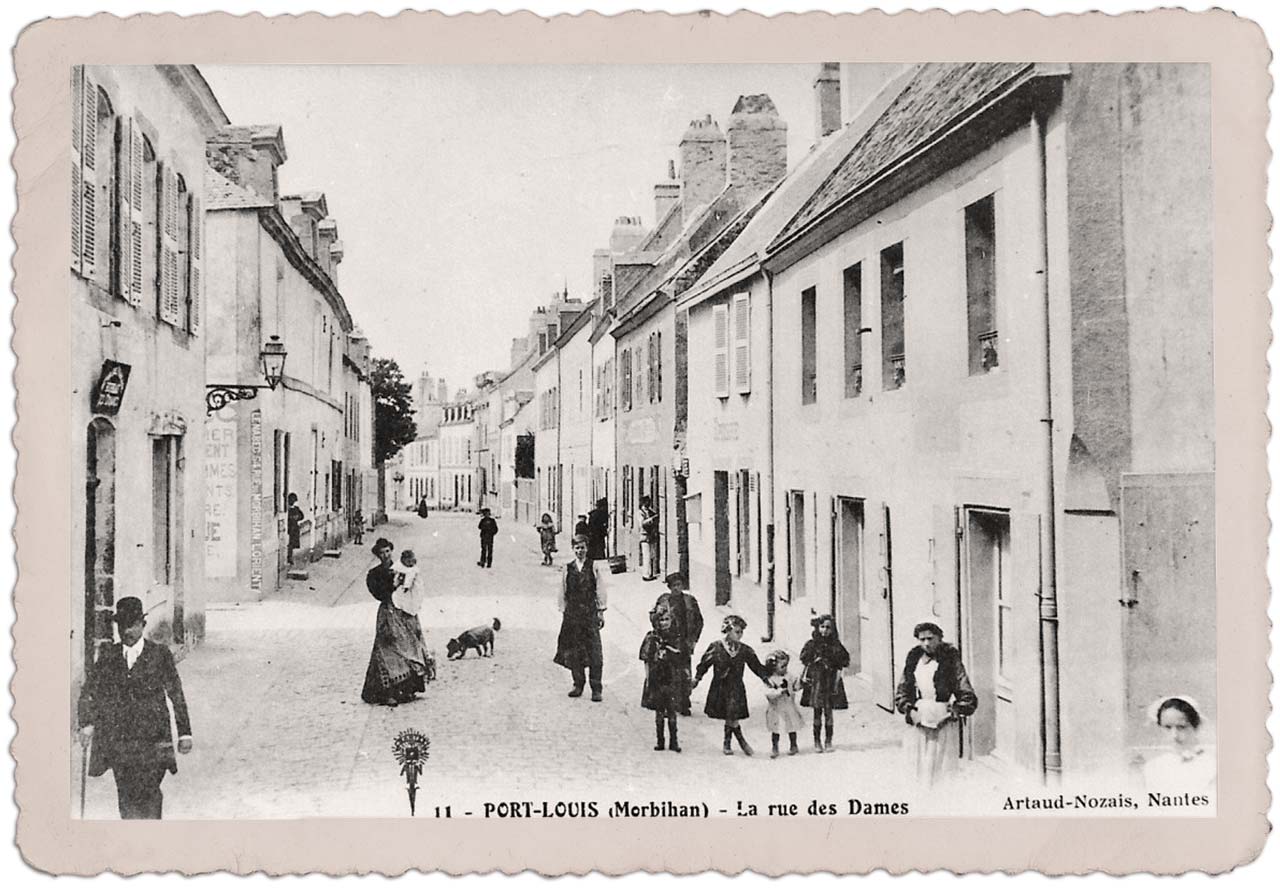

German troops first arrived in Port-Louis on June 21, 1940 – the day before Marshal Philippe Pétain’s government signed a surrender deal with the Nazis. Four soldiers including two officers turned up at a café in the town centre, marking the start of the five-year Occupation in Port-Louis. German soldiers took up residence at the citadel, then at a naval training school. Daily life was punctuated by RAF raids against the Nazis. The first bombings took place in late summer 1940. Houses were frequently damaged or destroyed. Several residents of the town were killed – including Louis and Pierre Guillo, two brothers aged 9 and 13, killed in their beds in March 1941.

The local economy suffered from the Occupation, while people had to endure rationing and high inflation. “Bread is scarce in Port-Louis,” regional paper L’Ouest-Éclair wrote on March 25, 1941. The crisis was still biting a year later. Women and children protested in front of the town hall in April 1942, demanding the same bread rations as in Lorient, just across the bay, where people were given extra rations in response to a severe lack of food. Port-Louisians also urged the authorities to provide sufficient supplies of fat, jams and spirits.

This was the background to Lisette’s adolescence. She wasn’t yet 15 when France capitulated and German troops came in to rule over her town. She showed contempt for the occupiers – as recounted in further detail in the file created by the post-war French state to give official recognition to deportees. The Service historique de la Défense in Caen, Normandy, part of France’s military archives, posted it to me. Lisette’s mother recounted in 1952 to the French gendarmes composing the file: “Marie-Louise had anti-German feelings. In the summer of 1942, a British plane crashed at Gâvres. The three aviators in the plane were buried at its cemetery. My daughter and some of her comrades raised money to buy three wreaths to place on the aviators’ graves. The Germans must have heard about it.”

But parts of this testimony are inaccurate. No plane crash was reported at the time at or near Gâvres, a town close to Port-Louis at the entrance to Lorient harbour. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission told me that the last British airmen to be buried at Gâvres Communal Cemetery were Norman Horace Whittaker, in July 1941, and Herbert Smith in November of the same year.

Did Lisette go and put flowers at their graves? Port-Louis police officer Camille Morillon gave the gendarmes the following version: “I knew Mademoiselle Moru very well. She was a young girl with anti-German sentiments – it really hurt her to see those soldiers singing in the street. Shortly before her arrest, she’d bought wreaths to lay on the graves of two British aviators buried at Gâvres cemetery.”

The British aviator’s provisional grave at Gâvres cemetery. © Steve Males

A friend of Lisette’s, Marguerite Coriton, also remembered this episode. The 96-year-old lady told me her memories over the phone. She went to school with Lisette. “It’s like I can still see her,” she said, describing Lisette as a “lovely, very kind young girl”. Coriton told me they went out as a “group of three or four friends, all girls, who all hated the Germans” to put down a bouquet at the spot where “a British parachutist fell”. But she couldn’t specify the date.

“We were reckless, you know; we’d risk our lives,” Coriton said. “I’d really thrown caution to the wind. One time I threw a Cross of Lorraine at a German’s back – I ran away and didn’t get caught.”

Her brother Lucien didn’t have the same luck. The young Resistance member was arrested in April 1944 while he was on his way back from a mission. He was executed in the square of his native village, Landaul, about 20 kilometres away from Port-Louis. “It’s very difficult to talk about it,” Coriton said. “I still feel a lot of grief, even at my age. We saw him in such a sad state – martyred – while he was so young and beautiful. That’s all I have to say,” she concluded, with a last sob before hanging up.

The secret list

During the summer of 1941, Lisette went out with a boy, the friend she was arrested with. His name was Louis Séché. He also had a deportee file at the Service historique de la Défense. I learned that he was born in Nantes on April 19, 1922. He was three years older than Lisette, an electrician and the only son of the head of the Port-Louis gas plant.

After the war, Séché’s father also explained to the French authorities what happened before his disappearance. He didn’t say anything about the bouquet story. But he did recount an event from June 1942. Lisette and Louis had gone to the beach for a swim. “There were several Germans with French girls. When my son arrived, the Germans wanted to drive him away. He took a pencil and a piece of paper and wrote down the names of the girls who were with them. Then he left.”

Lisette and Louis didn’t hide their aversion to the German occupiers and those who spent time with them. They appeared to have the same views and – above all – the same temperament.

I discovered that Louis’s family had left the area a long time ago. After trawling through genealogy sites for hours, I managed to find his cousin Anne Toucanne. Aged 86, she still lives on France’s Atlantic coast, but further south in La Baule, in the Loire-Atlantique region.

“His father was one of my mum’s brothers; they were very close,” Toucanne told me when I visited her home. “I knew ‘Little Louis’ quite well; we called him that because his father had the same name.”

Toucanne showed me her family photo album. I saw the yellowed pictures of her uncle, her aunt and her cousin Louis, who sometimes came to stay with her family in Saint-Herblain, near Nantes. “Little Louis had a penchant for mischief,” she recalled. “One time he went down the well in the bucket as a joke – it made me feel sick! He really was quite something.”

She was just eight when her cousin disappeared overnight in 1942. The adults were very worried. They didn’t say much. “I’ll give you the photos of Louis,” she told me as I was about to leave. “Soon there won’t be anyone left to remember him.”

Nearly eighty years have passed. The Second World War is slipping out of living memory and a lot of the people involved are now dead. But as I carried on searching in the archives, I discovered the key to the hitherto nebulous story of why Lisette was deported. It was in the archives of Ille-et-Villaine, a Breton county to the northeast of Morbihan.

I found a case file from the Morbihan courts – concerning three women investigated for denouncing Lisette and Louis. The papers were musty and dusty. They almost fell apart in my hands when I looked at them in the reading room. But I could see the tragedy unfolding before my eyes.

In June 1942, Lisette was working at the canning factory. One of her colleagues was a girl of a similar age referred to as Mademoiselle G. When questioned after the war, the latter recounted: “Lisette Moru was a workmate. She noted the names of all the women who worked for the occupying troops so that reprisals could take place when the war was over. […] She gave the list to a boy from Port-Louis, an electrician called Séché. I didn’t know what he was doing with it.”

Mademoiselle G. told her mother what Lisette was doing. The mother worked for German customs in Port-Louis – and told one of her colleagues what her daughter had said. A customs officer called Jean Hirsh overheard their conversation. When the Germans questioned the two women a few weeks later, they had “no difficulty” telling them about the list Lisette and Louis had drawn up, according to a report drafted soon after the Liberation.

On August 21, 1942, the German authorities searched the boy’s home. “I returned home at about half past midnight,” Louis’ father later recounted. “I didn’t see anything untoward to start with – but then I heard this bang coming from my son’s room. I went in straight away and found three men dressed like civilians rifling through the furniture. I asked them what they thought they were doing. They said they were looking for what they had the right to find. Louis turned up – and they started interrogating him. They’d come to get the list. When they searched the whole house, my son gave them the list.” It contained “the names of 36 people who frequented the Germans,” he added.

A few days later, the occupiers searched Lisette’s family’s house. “The Gestapo searched my home in September,” her mother recounted after the war. “They didn’t find anything out of the ordinary, except a Cross of Lorraine in my daughter’s room.”

On December 8, 1942, Lisette and Louis were summoned to the local German military headquarters. “My daughter obeyed the summons, thinking they had nothing on her,” Suzanne Moru recounted. “At about eleven o’clock she was still in there, so I asked one of the Germans what was going on. He said she was going to prison for defaming the German army. At the start of that afternoon, four German gendarmes escorted my daughter to Lorient train station, travelling to Vannes [also in Morbihan].”

Louis’ mother Marie-Anne Séché gave similar testimony: “He was summoned to report to the German military headquarters on December 8, 1942. He left the house at seven o’clock that day. We never saw him again.”