But Syria is far from being safe. For most young Syrian men, return is synonymous with forced conscription in the government’s army. Three days after arriving to Syria, Rayan’s son-in-law Nasser was abducted from his parent’s house. “They [Nasser and his wife Mariam] were both terrified the day they left,” Rayan said, “but he was so sure he would have found a secure job once he was back.” No one knew what had happened to Nasser until a month later, when he sent a picture of himself: alive, but dressed in an army uniform, standing in a government training camp in Damascus.

According to the Syrian authorities, men returning from exile should be given a six-month grace period before being conscripted. But this promise is often ignored as the regime desperately needs young men to fight in their depleted and battle-weary army. During that month, Mariam gave birth to her first child, Sham. She now lives with Nasser’s mother in the side of their house that has not been damaged by shelling.

Close to Rayan’s camp, Sheikh Ahmed and his 74-year-old father Walid greet us in the cold wide basement of a local mosque. The air is heavy as we are served the usual cup of welcoming tea. Walid fled back to Lebanon after returning to Syria in July 2018. He too had signed up as a voluntary returnee with the Lebanese General Security. Returning to Homs, Sheikh Ahmed had believed his father’s old age would have been a guarantee of safety. But he was wrong.

"When we realised he had disappeared, we had to pay $500 to an officer at the checkpoint just to find out in which prison they had taken him." Choosing his words carefully, Sheikh Ahmed outlines the workings of a well-functioning system of blackmail. "The judge sets a price on each detained prisoner according to the charge and to their knowledge of the prisoner's family's wealth.” Sheikh Ahmed was able to collect $5,000 from family and friends in Lebanon and send them to the judge in Damascus through a trusted contact. "Half of that money will go to the general in charge of the prison, the other to the judge. It's a way for the regime to reward its cronies," he explains.

Despite his age, Walid was held for a total of 50 days and tortured repeatedly, locked in small cell with a dozen other detainees. His family had to pay another $200 to be issued an official letter declaring his father was innocent of all charges. “How can we trust the regime to return if they even arrest an old man who has completed the vetting process and been guaranteed his safety by the Syrian security?” Sheikh Ahmed asks. His story is not unusual. The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), a monitoring group that records arbitrary detentions and disappearances across Syria, recently documented 1,916 cases of arrest of returning refugees to regime-controlled territory (including 219 children and 157 women). At the time, 784 remained in detention, and 638 had been forcibly disappeared. Fifteen were reported to have died as a direct result of torture at the hands of the Syrian regime after their arrest.

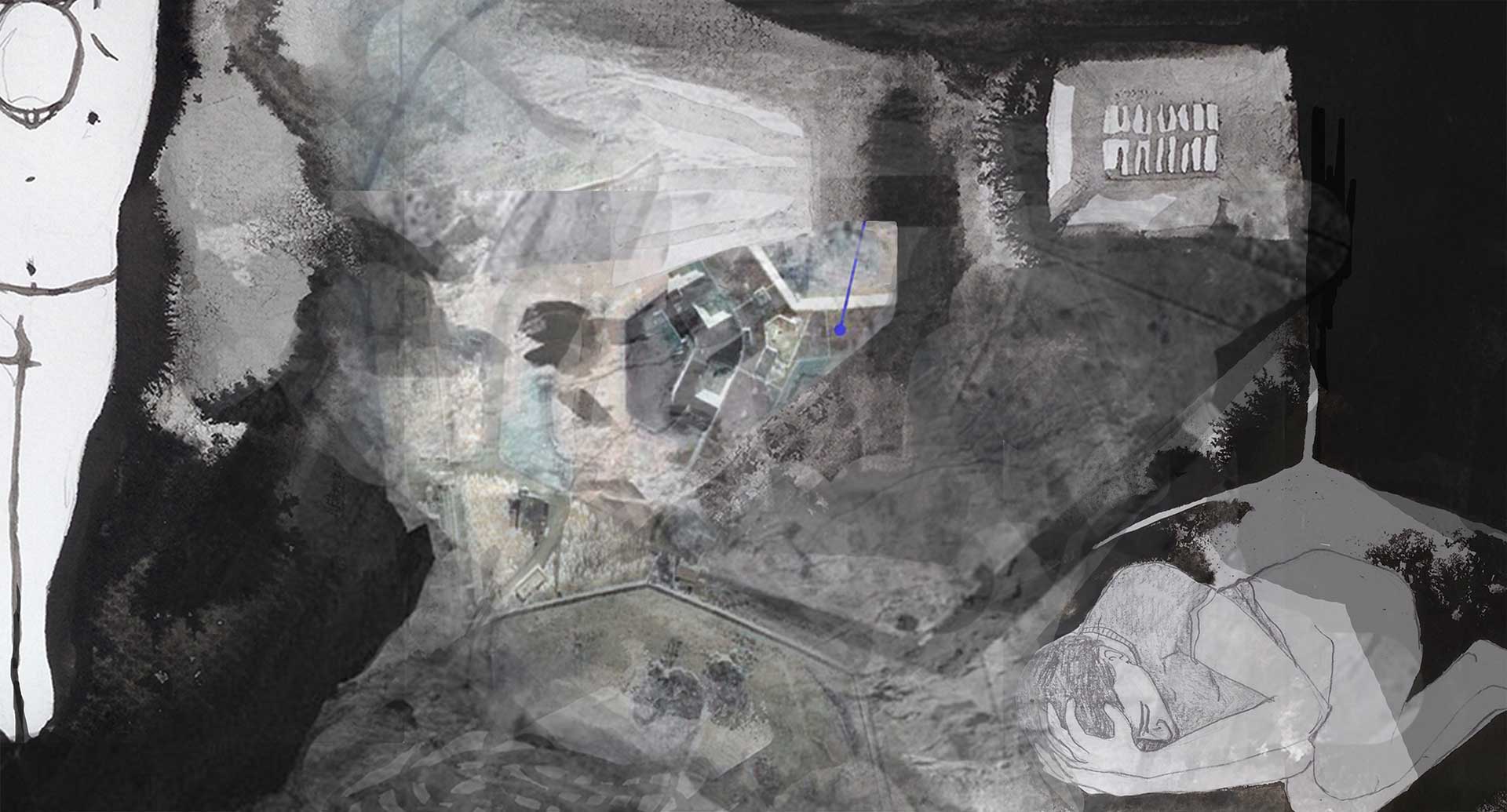

Fearful that Syria’s No. 10 law could allow the Syrian regime to seize his property if he did not register his ownership, Sheikh Ahmed had hoped his father could register their family home in Homs. “It’s a miracle it survived the bombing. The government has taken everything from me, I didn’t want to lose my home as well.” Since reconquering much of the country, the Syrian regime has been passing new laws allowing authorities to confiscate property and make space for large multi-billion reconstruction projects, in the hope of attracting much needed foreign investment. Such projects have been planned in poorer Sunni neighbourhoods such as Bab Amr in Homs and Haidaria in Aleppo, districts that have been associated with the opposition, evidence that reconstruction and re-population is strategically meant to fragment communities that are hostile to the regime.

“Syria is not a safe place for anyone to return today, and this is beyond doubt,” Syrian lawyer Anwar al-Bunni explains from his office in central Berlin. Heading a center for legal studies on Syria, Mr al-Bunni has dedicated the last five years of his life to proving this statement - informing the German Interior and Foreign Ministries as well as judges of European courts about the risks and dangers facing Syrians who return.

We meet him on the fifth anniversary of his arrival in Germany. He escaped Syria in 2014, after having spent four years in government prisons for his work defending Syrian activists. “War is not what Syrian refugees are scared of. It’s the impunity of the security forces that makes life in Syria impossible.” Al-Bunni is amongst the lawyers who worked on the Caesar Files, a series of documents holding nearly 55,000 photographs of forensic evidence of torture, starvation and deaths of detainees inside Syria’s government-run prisons. Smuggled to Europe by a former regime officer now code-named ‘Caesar,’ these documents provide the evidence that is being used in the prosecution and arrest of high-ranking regime officers currently in Europe disguised as refugees.

“We are working to tell the world exactly who the criminals are. Once incriminated, these people will not be able to sit at the negotiation table and decide on the future of Syria,” al-Bunni’s words resonate loudly in the room. “They will be caught one day, but until then, no-one can openly do business with these criminals now that there is a European arrest warrant against them.”

But with Syria’s reconstruction estimated at $400 billion, many actors are assessing Syria’s reconstruction as a business opportunity. Russia and Iran, the regime’s largest allies, remain cash-strapped from years of funding Syria’s war. But countries such as China and Brazil are considering large investments, whilst Lebanon and countries hosting millions of Syrian refugees are keen to part-take in reconstruction, so as to facilitate the return of their many undesired guests.