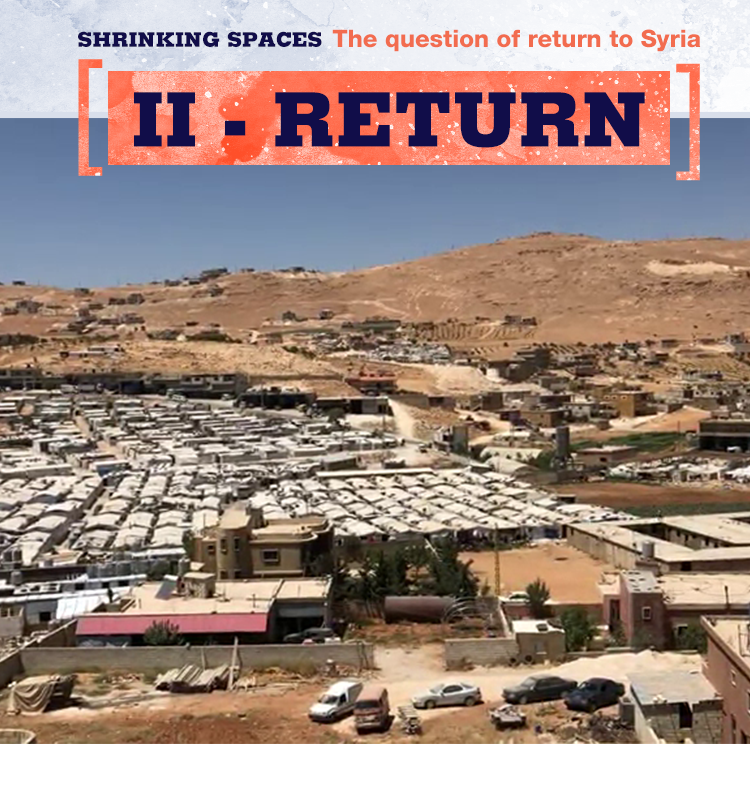

He receives us in his brand-new office. The old one was severely damaged in the 2014 ‘battle of Arsal’ when hardline Islamist groups from Syria briefly overran the town. “Our security is good now,” Mr Houjeiry assures us. “Today our main problem is economic. Syrians outnumber Lebanese locals three to one. There is a lot of competition for work and we have to deal with four times the amount of waste we used to have.” Asked whether he thinks Syrians should go back, he cuts us short. “We all know people are here because they are scared of the Syrian government. I hope they will return soon, but without force and only when it is safe to do so.”

Mr Houjeiry’s stance is not a popular one: many Lebanese are tired of the pressures of hosting so many Syrians and want them to leave now. Led by the country’s strongman foreign minister, Gebran Bassil, anti-Syrian rhetoric has spearheaded a political campaign blaming Syrian refugees for Lebanon’s unemployment rate and economic woes - even accusing the UN and international organizations of intimidating refugees who wish to return voluntarily. “I agree with Minister Bassil,” echoes Tony Abood, Mayor of Minyara and staunch advocate of Syrian’s repatriation. "Most Syrians would be welcomed back with no risks at all. The only reason they stay here is because of the help they get from the UN.” Encouraged by such rhetoric, and in the absence of a central strategy with how to deal with the refugee influx, many municipalities all across the country have imposed curfews, whilst incidents of collective punishment against Syrian communities are on the rise.

Such pressure is leading many Syrians to leave Lebanon. “He couldn’t stand this life any longer,” sighed Rayan when telling us of her son in law Nasser, married to her eldest daughter Mariam. After he was badly beaten by a Lebanese gang on his way back to work, Nasser had registered himself and eight-month pregnant Mariam with the Lebanese General Security, requesting to return to his hometown Sfireh, in the outskirts of Aleppo.

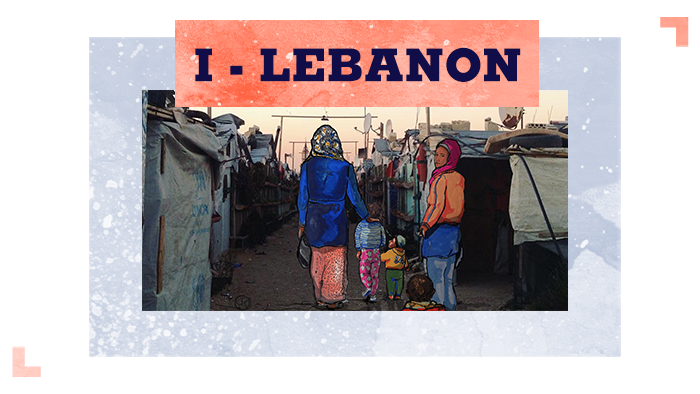

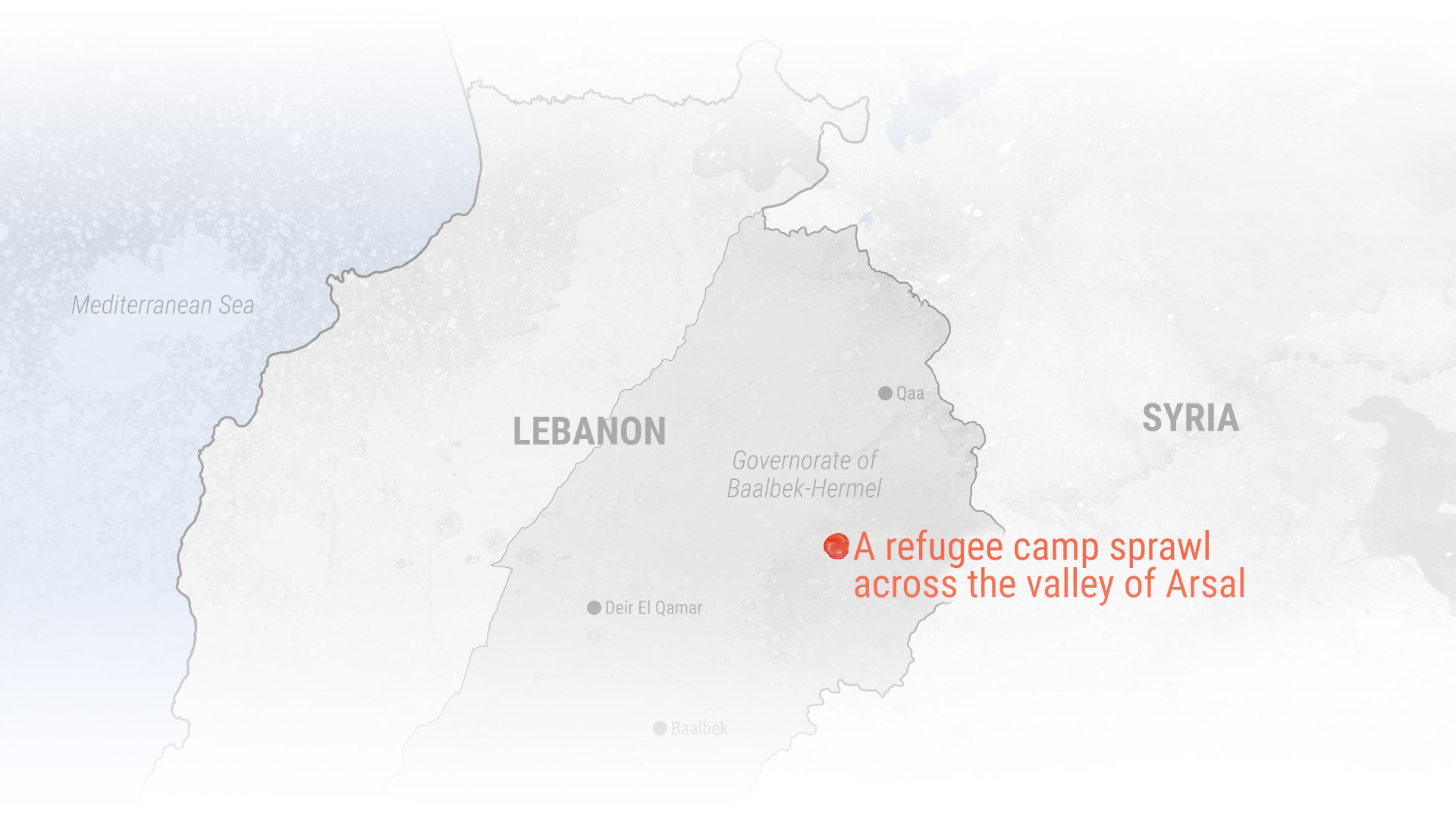

A woman walks between the tents and buildings on the Lebanese-Syrian border of Arsal. © David Suber

Lights from Syria can be seen from border town of Qaa in Lebanon. © David Suber

Since then, the Lebanese government have upped their efforts push out Syrians through mass deportations. Two days after the camp in Al Yasmine was demolished, 16 Syrian men at Beirut’s airport were deported to Syria after being forced to sign voluntary repatriation forms. Between May and August this year, Lebanon’s General Security confirmed it had deported over 2,700 Syrians, an average of 22 Syrians per day. Legal organisations and human rights groups in Lebanon and abroad have been warning the international community about the illegality and risks concealed in blending ‘voluntary’ return schemes with unlawful deportation practices. Since April this year, deportations of Syrians could occur through a simple verbal order from the Public Prosecution, justified by the government’s claim that Syria is “safe” for return.