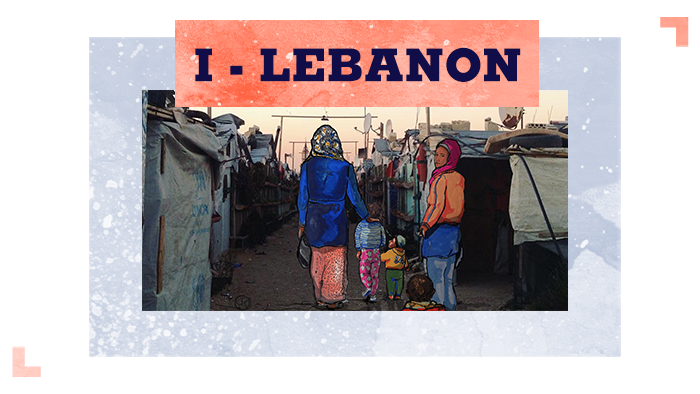

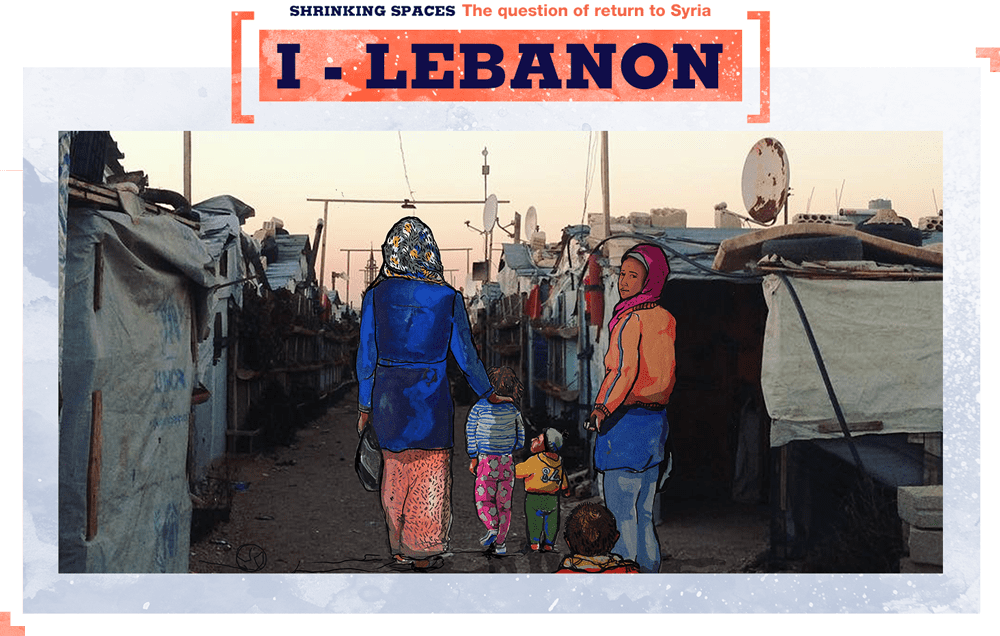

“We are your children, oh Syria, and by God’s word, we miss you!” sing a handful of children whilst excitedly running through a corridor of tents in a small Syrian refugee camp near the village of Tel Abbas, Akkar, Lebanon’s northernmost province. It’s the morning of Eid, a major Islamic holiday, and the children’s excitement cannot be contained any longer.

More than 50 Syrian families live here, in two rows of plastic tents tucked away amongst tobacco fields, just a few miles from the Syrian border. Concerned parents reluctantly watch over their kids. “It’s better for them not to play on the main roads,” says Rayan. Only a few days before, the Lebanese army raided a neighboring camp, arresting more than 14 men. Since then, everyone is on the alert.

A mother of seven, Rayan has taken the day off work. “It’s Eid after all,” she smiles. In 2013 Rayan and her children fled their hometown of Houla after surviving a massacre orchestrated by pro-regime paramilitaries known as shabiha. Their family has been living in Lebanon ever since, working the land of a Lebanese farmer for $5 dollars a day. Three of Rayan’s seven kids were born under a plastic shelter in Lebanon. “We rent a tent on the same field where we work, depending on the season. All of us work, except for Khalid of course,” she laughs gesturing to her youngest three-year-old son.

A Syrian man plays backgammon with friends over tea. © Luca Cilloni

Clothes drying outside the home of a Syrian family in Tel Abbas. © Luca Cilloni

Child labour is extremely common amongst Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Many families have no option but to send their children to school until they are old enough to work. Only one of Rayan’s sons attends school: “I know that education is important. I am not ignorant. But we cannot survive otherwise.”

Rayan’s husband Omar cannot work. Imprisoned in a Syrian prison for four years, he suffers from severe psychosis as a consequence of torture. He sits with us on a foam mattress, lighting one cigarette after another. Anti-psychotic medicine alleviates his epilepsy while pushing life away from his eyes. He rarely leaves the spot except for a monthly trip to the city of Tripoli, where he goes to collect his medication.

“It’s a nightmare every time we have to cross the checkpoint to Tripoli,” says Rayan. Like 74% of Syrians in Lebanon, Rayan’s family have no legal status, leaving them vulnerable to arbitrary arrest and detention. Omar has been arrested four times by Lebanese authorities at the checkpoints. “Not even a doctor’s note can prevent his arrest if they stop us. And every time they detain him, it brings back all the memories of torture in prison,” she says. “But what other option do we have?” Haloed in a cloud of cigarette smoke, Omar doesn’t respond.

A view of the local mosque in Tel Abbas. © Luca Cilloni

Silence is broken by Rayan’s brother Walid, who bursts into the tent laughing, his seven-year-old son closely behind, spraying plastic bullets into the air with his new toy gun. Walid and his son have been sharing the tent with Rayan’s family since their shelter in Al Yasmine camp was demolished by the Lebanese army on April 24th.

The demolition of Al Yasmine camp was the first of many, following the Lebanese Supreme Defence Council decision to heighten restrictive actions towards Syrian refugees, including the destruction of all concrete structures inside Syrian camps. “We knew there was an order related to the illegality of concrete buildings in camps, but when [the army] arrived here, they took down toilet cubicles and wooden structures too,” says Alaa, a social worker from Qatari NGO URDA. “Any tent that was unoccupied was also destroyed, whilst furniture and household appliances were loaded onto trucks and taken away.” In June 2019, over 5,000 structures were destroyed and more than 30,000 individuals made homeless. “We were lucky,” Walid smiles at his sister. “Not everyone had family they could stay with.”

Syrians destroy their own homes in a refugee camp in Arsal. © Sourced by the authors

The remains of Bebnine refugee camp burnt down by Lebanese youth after local tensions escalated into violence. © Sourced by the authors

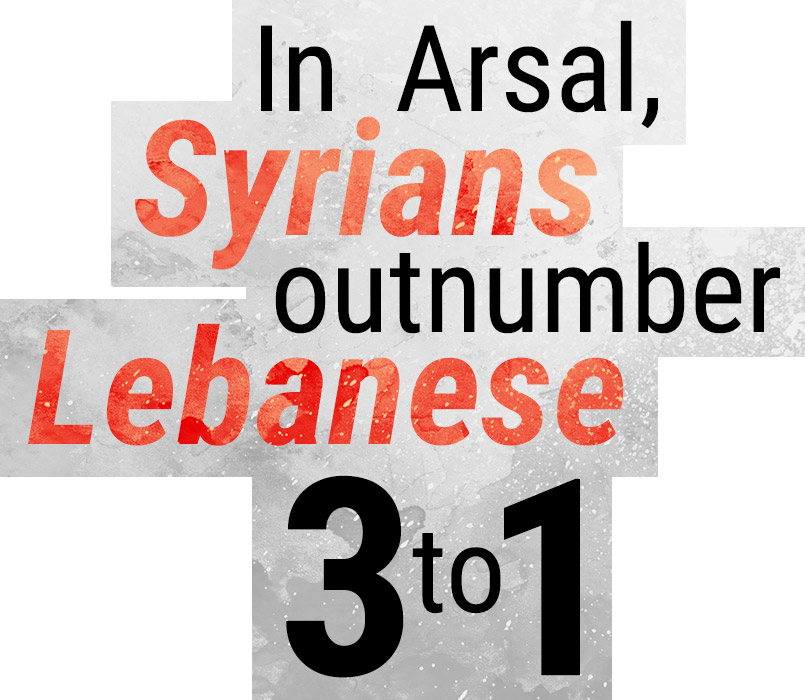

The border region of Arsal, in the Beqaa Valley, was hit the hardest by these demolitions. Most tents in Arsal had been built with concrete rather than canvas to withstand winter’s heavy snowfalls. After the first round of demolitions in June, the Lebanese army gave Syrians a week’s notice to destroy all concrete structures in their makeshift homes if they wanted to avoid more army raids. In July this year, tents housing 55,000 refugees were destroyed in Arsal alone. “The order to dismantle the camps was a political move to put pressure on Syrians to go back,” says Bassel Houjeiry, the Mayor of Arsal. “It has nothing to do with the administrative regulations that are being given as an excuse.”