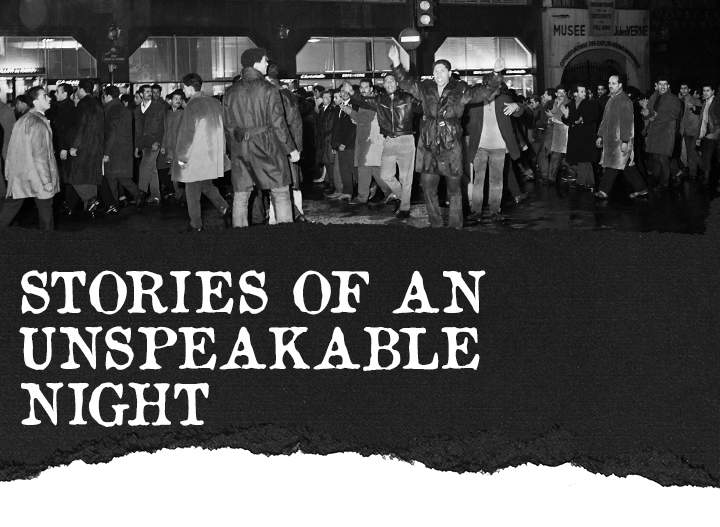

Historians are quite clear about what happened on October 17, 1961: Pierre Vidal-Naquet called it a “pogrom”; Paulette Péju called it a “racist attack”; Emmanuel Blanchard called it both a “manhunt” and a “colonial massacre”. But the truth was obscured for nearly three decades.

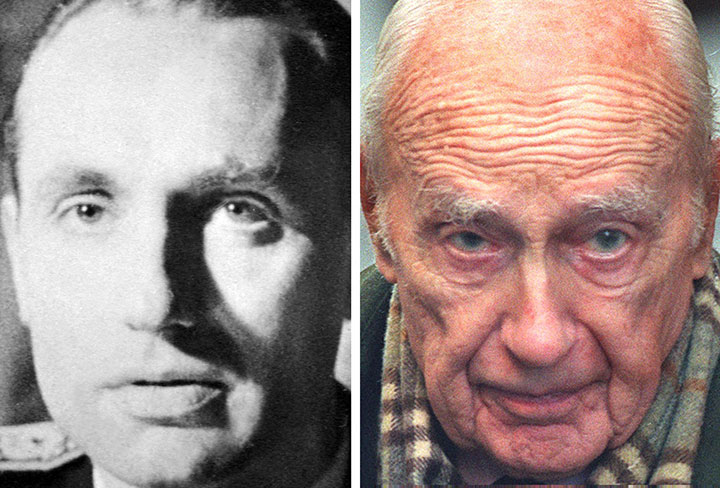

“Silence took hold; from 1962 [when the Évian talks turned into the Évian Accords granting Algeria independence] French society really wanted to forget the horror of the Algerian War,” said Riceputi. “At the same time, there was a political consensus on both right and left that those responsible would not be held accountable. The people responsible for October 17 stayed in politics for a long time: Maurice Papon was minister for the budget [from 1978 to 1981] under President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing; Roger Frey was President of the Constitutional Council [from 1974 to 1983]. There really was a kind of orchestrated omerta that even prevented access to the state’s public archives where they concerned this topic. People wanted October 17, 1961 to be invisible – so that no one would talk about it.”

Manceron highlights the cover-ups. “First of all, the French authorities wanted silence about this. Prime Minister Michel Debré, head of Paris police Maurice Papon and Interior Minister Roger Frey orchestrated this massacre. President de Gaulle wasn’t behind what happened. But he chose to say nothing – he needed to avoid alienating too many people who brought him to power in May 1958, especially since the OAS wanted to kill him. So he had to be keep Debré, Frey and Papon close,” explained Manceron.

Several months later, on February 8, 1962, the police violently repressed a demonstration for peace in Algeria and against the OAS organised by the French Communist Party (PCF) – killing nine people at Charonne metro station in eastern Paris. Ergo, the French hard left had a reason to make people forget about October 17, 1961. “The PCF was divided over the Algerian question, so it wanted to emphasise what happened at Charonne and minimise what happened on October 17,” said Manceron.

“Relations between the FLN and the PCF were very bad in October 1961,” Riceputi added. “The October 17 demonstration was an autonomous act by the Algerian diaspora in Paris, which had nothing to do with the French left. Consequently, the left had no reason to decry what happened after the massacre. Instead, what it did want to recognise as a major event in the repression of the Algerian pro-independence movement was their own demonstration against the OAS, in which French people were killed.”

There was a massive demonstration in response to the Charonne killings – one of the largest in French history, with more than a million people taking to the streets. “This was the foundation of Charonne’s place in French history, and the memory of it was evoked ceaselessly,” said Riceputi. “There was nothing like this to anchor October 17 in France’s collective memory. There were no funerals. There were people buried covertly… There were corpses retrieved from the Seine, corpses impossible to identify, there were people sent back to Algeria. It was a colonial massacre.”

But the FLN running the new Algerian state (the FLN continues to rule Algeria today) also wanted people to forget about October 17. “In 1962, [then Algerian head of government] Ben Bella told Marcel Péju, to whom he was close, that it wasn’t opportune to publish ‘Le 17 Octobre des Algériens’,” Manceron said. The demonstration had been organised by the French branch of the FLN – and since Algeria was now independent, the FLN there considered them opponents.

A turning point in the 1980s

In 1984, it was a novel, a thriller, that gave October 17 a place in the French collective imagination. Didier Daeninckx’s “Meurtres pour Mémoire” [Murders for Memory] featured characters brutalised by racial profiling. A year later, Michel Levine’s “Les Ratonnades d’Octobre” [The Racist Attacks of October] was published. In 1986, Mehdi Lallaoui, whose father experienced the events of that night, published “Les Beurs de Seine” [The North Africans of the Seine].

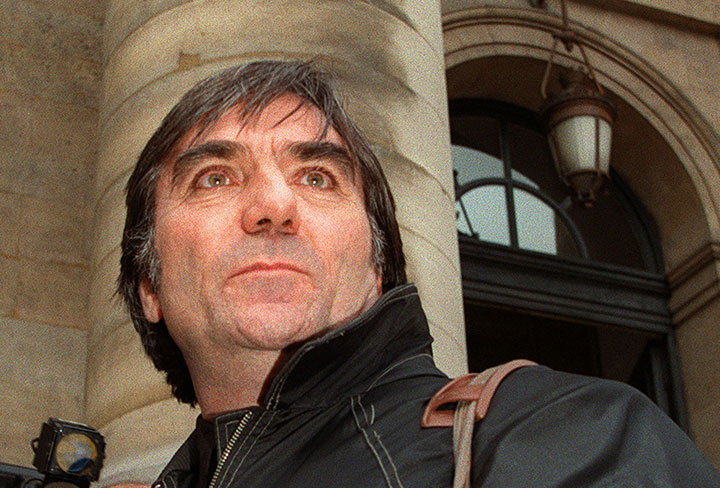

In 1991, Lallaoui, along with journalist Samia Messaoudi and historian Benjamin Stora, set up the association, Au Nom de la Mémoire [In the Name of Memory], which published Anne Tristan’s “Le Silence du Fleuve” [The Silence of the River] which included Elie Kagan’s photographs. The same year, Jean-Luc Einaudi published “La Bataille de Paris, 17 Octobre, 1961” [The Battle of Paris, October 17, 1961], which featured a preface by historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet. It was the product of five years of investigation in both France and Algeria.

Einaudi, who died in 2014, aged 62, was an “extraordinary figure”, noted Riceputi. “Although he had no academic training, Einaudi managed to establish a counter-narrative that exposed the official version as fake… He managed to show what happened without any access to the archives – he was initially blocked from accessing them – and produced pioneering work. In doing so, he collected testimonies from police officers, journalists and victims, even going to Algeria in this process. What Einaudi did was of decisive importance. Before him, the event had seemed to many people implausible, impossible even.”

Einaudi was also the man who defied Papon. In 1997, the former head of the Paris police was tried in Bordeaux for his role in the deportation of Jews from France to Nazi concentration camps between 1942 and 1944. “The Jewish civil parties in the case and the [anti-racism organisation] MRAP asked Einaudi to come and testify about Papon’s responsibility for October 17, 1961,” Riceputi noted. It was the most publicised trial in postwar French history.

The trial was an extraordinary platform for revelations about October 17. “There was a manhunt ordered by the head of the Paris police force, with 6,000 people rounded up, and people killed in the grounds of the Palais des Sports [an arena at Paris’s southern edge],” Einaudi told the court.

Papon sued Einaudi for libel in 1999, in response to the publication of an opinion piece in Le Monde the previous year. “In October 1961, there was a massacre in Paris carried out by police officers acting under Maurice Papon’s orders,” Einaudi wrote in that article.

The trial gave Einaudi “another opportunity” to establish the truth, Riceputi said.

Einaudi won in the libel case. Not only that: the court accepted in its verdict that “massacre” was an apt term for what took place on October 17, 1961. It was a huge turning point.

From then on, October 17, 1961, had a place in the French collective memory. Each year, associations organised commemorative events in Paris to pay tribute to the victims.

“Today, nearly 50 cities have commemorative plaques,” said Messaoudi. There are many in the Paris region – but the best is in Nanterre [a suburb to the west of Paris], with a boulevard, a bus stop and a plaque [dedicated to the victims’ memory]. In La Courneuve, there is a beautiful stone tablet inscribed with the names of the people killed.”

Many activists, NGOs and historians are now calling for official recognition that this was a “state crime”.

In October 2012, then French president, François Hollande, took a step in that direction when he wrote in a statement, “On October 17, 1961, Algerians demonstrating for the right to independence were killed in a bloody crackdown; the Republic clearly recognises these facts. Fifty-one years after this tragedy, I pay tribute to the victims.”

The day before the 60th anniversary of the massacre, Emmanuel Macron joined commemorations at the Pont de Bezons, a bridge in Paris’s western suburbs that saw horrific police violence that night.

Instead of Macron speaking at the event, the Élysée Palace posted a written statement online saying that, for the French Republic, “the crimes committed that night under the authority of Maurice Papon are inexcusable”.

LIVE | Commemoration on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of October 17, 1961. https://t.co/5Ggy7sbDtr

& mdash; Élysée (@Elysee) October 16, 2021

While it was an unprecedented gesture for a sitting French president to commemorate the victims of October 17, 1961, many historians found the press release disappointing because it contained no reference to Papon’s role as Paris police chief. Nor did it refer to the responsibility of senior cabinet ministers.

“The press release emphasises that the Algerians’ demonstration was illegal – but they were protesting against a discriminatory curfew,” Riceputi said. “It’s astonishing that, at this point, the French state can’t say that the demonstration was perfectly legitimate. Yes, Macron went further than Hollande, but there are some things a president still can’t say in the current political context.”

“It’s another small step in the right direction – but it’s still not enough,” Manceron said. “Macron recognised the Paris police’s crime; however, we want recognition that this was a state crime, and we want access to the archives opened up.”

“Macron’s statement is far less than what people had every right to expect,” added Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison, a historian and head of the association 17 Octobre, 1961: Contre L’Oubli (“October 17, 1961: Against Amnesia”). “It’s ridiculous to suggest that the government and the then PM [Michel Debré] weren’t involved and that Papon could have acted on his own initiative throughout October 1961 – and on the night of the 17th in particular.”

For Hadjam, “it’s progress – but only a bit”. She said she was hoping for “more” because “Papon wasn’t acting alone; people were tortured and massacred and the powers-that-be knew what was going on”.

“What about the archives?” Hadjam continued. “Why are the archives about the Seine still closed, ensuring that the truth remains hidden?”

“The denial that goes on is unbearable – the fact that the state can’t refer to the Paris police, Michel Debré or de Gaulle.”

Despite decades of progress in uncovering the truth, it remains too hard to tell the full story of what happened on October 17, 1961.