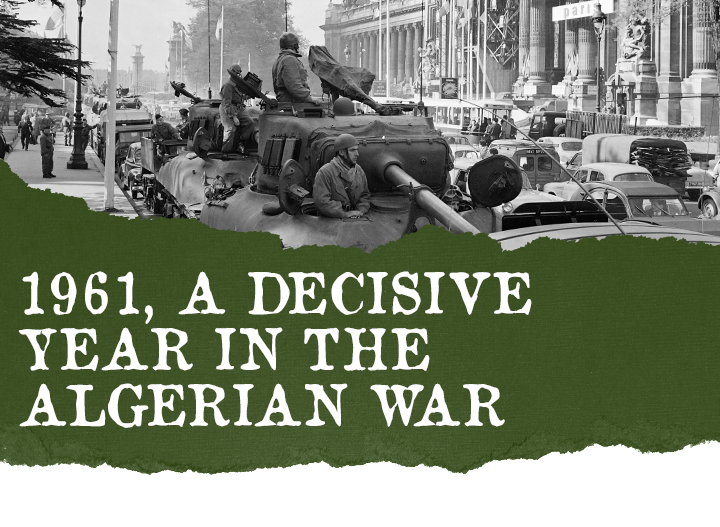

The Algerian War of Independence had entered its seventh year when the Paris massacre occurred and France was in a state of crisis over the decolonisation struggle.

In May 1958, the war led to the collapse of France’s Fourth Republic (a system characterised by frequent changes of government and a weak executive branch). A perception that successive French governments were not doing enough to hold onto Algeria prompted a bloodless military coup. Charles de Gaulle, the revered leader of Free France during World War II, returned to power with widespread political support. Six months later, he became the founding president of France’s Fifth Republic, characterised by a strong presidency, which endures to this day.

De Gaulle visited Algeria days after taking power – making his famous proclamation, “Long live French Algeria!” But de Gaulle knew that Algerian independence was inevitable and that the brutal conflict needed to end. De Gaulle staked his political future when he called a referendum in January 1961 – in which 75 percent of the French people voted for Algeria’s self-determination.

Diehards saw de Gaulle as a traitor and vowed to keep Algeria French at all costs. A month after the referendum, Jean-Jacques Susini and Pierre Lagaillarde set up a paramilitary group, the Secret Armed Organisation (OAS), to achieve this end. The OAS motto was a vow to “strike where it wants, when it wants”.

On the night of April 21 to 22, four OAS-supporting French generals – André Zeller, Edmond Jouhaud, Raoul Salan and Maurice Challe – tried to seize control of Algeria in a putsch. But four days later, the French authorities finally prevailed over the renegade military officers. Challe and Zeller were imprisoned, but Salan and Jouhaud went underground and took over as OAS leaders.

In May 1961, France and the FLN’s political wing, the Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA), started official talks in the French Alpine spa town, Évian. But the negotiations stopped abruptly the following month, as France insisted on retaining control of the geostrategically significant Sahara region, which Algeria refused.

That turbocharged the violence once again – and not just in Algeria. “From August 1961, French opponents of Algerian independence were trying to provoke violent repression of the FLN within France, thinking that this would help squash the talks,” explained Gilles Manceron, author of “La Triple Occultation d’un Massacre” [Three Cover-ups of a Massacre], published together with another historical study, “Le 17 Octobre des Algériens” by Marcel and Paulette Péju.

But things did not unfold as the anti-independence diehards expected: de Gaulle renounced France’s claim to the Sahara, allowing talks to resume.

The return to the negotiating table went badly for some, including in the government. “Many people who’d supported de Gaulle’s return to power in 1958 – indeed his prime minister, Michel Debré – were opposed to Algerian independence. Debré was responsible for maintaining order in France, and he appointed one of his own men, the hardliner Roger Frey, as interior minister,” noted Manceron. Another hardliner, Maurice Papon, had been head of the Paris police since March 1958.

“The repression started with police raids, but there were also unofficial sections of the police playing a role like that of Latin American death squads,” Manceron continued.

The FLN ramped up the pressure with terrorist attacks in France – notably in Paris – as soon as the Évian talks were suspended. The police, as a symbol of the French state, were a particular target.

“It was a kind of war in Paris,” said Jean-Marc Berlière, a historian of the French police. “Sentries would stand in concrete blocks outside police stations surrounded by barbed wire. From January 1958 until the end of 1961, 47 police officers were killed and 137 wounded – and that’s just those working for the Paris force.”

Paris police HQ, a ‘state within a state’

The Paris police force was completely independent of the national force. It was a “state within a state”, said Berlière, noting that Paris had more police officers than the total number for the rest of France. People often said the head of the Paris police was “more powerful than the interior minister because he had thousands of officers under his command in the French capital”, Berlière continued.

Papon was in Algeria for much of the 1950s, in charge of the police in the northeastern city of Constantine. When he returned to France in 1958, he decided to make life harder for Algerians in Paris, with a marked uptick in identity checks of “French Muslims of Algeria” (FMA), as they were officially called.

On both sides of the Mediterranean, Algerians known as harkis fought alongside the French against the FLN. In 1959, Debré created the FPA, an auxiliary police force made up of harkis to fight the French branch of the FLN. Many of those harkis and their family members were “murdered, tortured or pressured” by the FLN, according to Berlière. “They displayed the same savagery in return.”

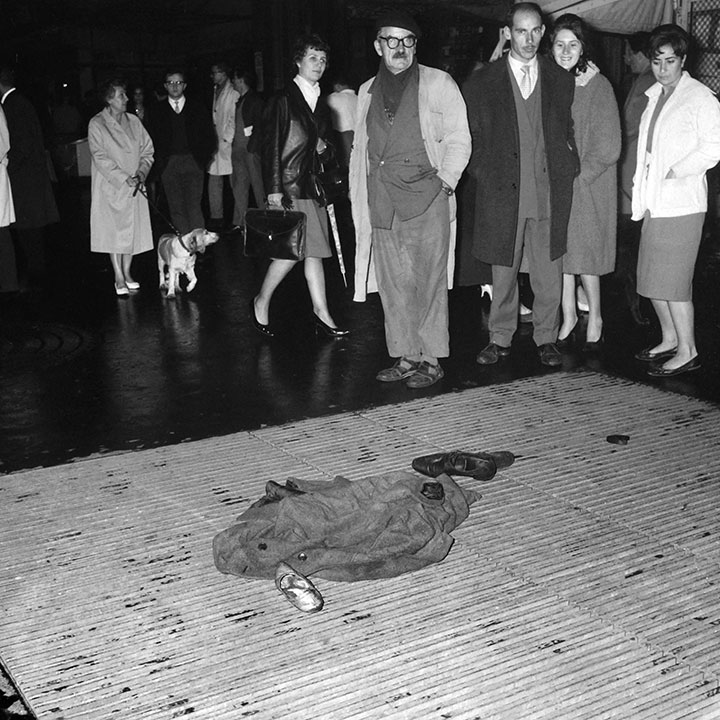

The FPA engaged in raids, executions and brutal interrogations of their FLN opponents. “Bodies of Algerians were fished out of the Seine every day,” said Fabrice Riceputi, author of “Ici, On Noya les Algériens” [Here, We Drowned Algerians].

“Imperialist racism was very prevalent in France at the time and Algerians were its principal target,” Riceputi added. “Extreme police brutality could go unpunished, swept under the carpet by state institutions – including a justice system that refused to prosecute crimes carried out by the police and a media with enormous reach that relayed false versions of such events.”

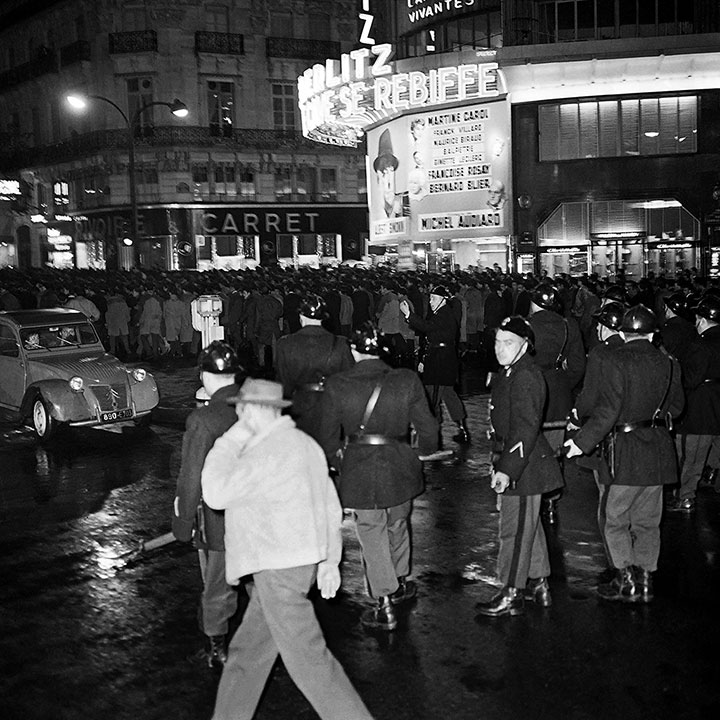

The situation deteriorated even further in autumn 1961. Nerves were frayed all round. Each and every terrorist attack against the police demoralised them further. “In August and September ’61, eight Parisian police officers were killed,” noted Berlière. Discontent was brewing in police ranks, with fears of insubordination, strikes and demonstrations. The government was paralysed. They did not want a repeat of the police strike and protests of March 1958, which was a catalyst for the fall of the Fourth Republic, explained Berlière.

Police unions were calling for a fierce response against the FLN. Papon gave them what they wanted. “For every blow against us, we’ll fight back with ten,” he said on October 2, 1961 at the funeral of a slain police sergeant. Papon even encouraged the police to shoot first.

“The OAS had infiltrated the ranks of the police. So, to ensure the force stayed loyal to the government, Papon, Debré and Frey gave these police officers what they wanted, notably the curfew, which was the cause of the October 17 demonstrations,” said Berlière. On October 5, Papon signed a curfew decree covering just one category of citizens: the French Muslims of Algeria or FMA.

Papon’s order came into effect the next day.

“In order to put an end to criminal acts of the terrorists without delay,” the decree read, “the police headquarters has decided on some new measures. To execute these new measures, Algerian workers are urgently advised to stay indoors and not be out on the streets of Paris or the Paris suburbs, especially between 8.30pm and 5.30am. Those who have to go out during these hours because of professional obligations may ask their local authorities for a certificate that will allow them to do so, after their request has been validated. It has been observed that most of the attacks have been carried out by groups of three or four men. Consequently, French Muslims are strongly advised to travel alone, since small groups risk appearing suspicious to police patrols. Finally, the head of the Paris police has decided that drinking establishment frequented by French Algerian Muslims must close every day at 7pm.”