‘They were screaming, they were moaning’

Serge Rameau was born in December 1946 in the Romanian capital, Bucharest. Before the Iron Curtain came down over Eastern Europe, an air hostess managed to get him to freedom in the West. It took his parents three years to reach Paris on foot. Rameau had refugee status in France until he became a French citizen aged 20.

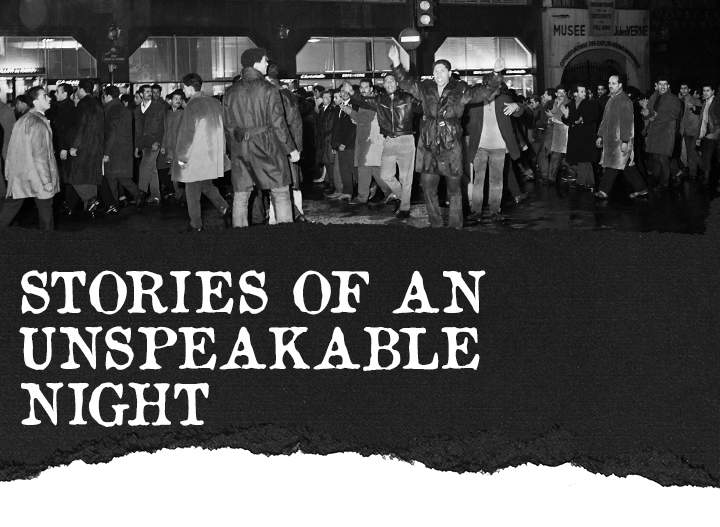

Rameau was a teenager on October 17, 1961, when he found himself in the middle of the demonstration as he left the Place de l’Étoile metro station. He saw the police beating Algerians. Traumatised by the violence he saw and the screams he heard, Rameau was determined to bear witness to what happened on that horrible night.

The retired dental surgeon now lives back in Romania. A recipient of both the French Legion of Honour and Order of Merit, Rameau now serves as the head of the war memorial organization, Le Souvenir Français.

“I was 14 years old, a boy scout. I lived with my grandmother at 11 Boulevard Pereire in the 17th district [in the northwest of Paris]. On my way back from the scouts, I’d get off at Étoile metro station, then I’d take the bus… When I got out of the station, it was pandemonium all around. I had no idea that a protest was going on; I was young, I didn’t really follow the news. I didn’t have a clue that the Algerians had called a demonstration – otherwise I wouldn’t have got off the metro at Étoile.

“It was 5pm, but in October, it’s already a bit dark at that time – not completely, but it’s twilight. There were only men there. The police would catch the men at the metro station exit and hit them. They forced them into police vans by pricking them with needles. It traumatised blanme. They were screaming, they were moaning. I remember the cries of pain, of violence.

“I got away from there as soon as I could. I didn’t run because I didn’t want to attract attention. I was very aware that running in front of the police was not a good thing to do. I walked fast to the bus station – but I didn’t go to the nearest one; I went further away.

“I was completely traumatised by what happened. We were accustomed to seeing violence at the time. There were sandbags in front of police stations. I was in high school in the 16th district [in western Paris] – and they’d search our school bags. One day, I was on my way to the dentist with my grandmother on Boulevard Bonne-Nouvelle, and right in front of me a guy took out a gun and shot an Algerian in the head.

“So we were living in this particular atmosphere – but at the same time, I couldn’t imagine the police doing what they did. Back then, we had great respect for the police, for authority, for the uniform. It was incomprehensible to me.

“My uncle had a business importing rugs. His company, Les Deux Pélicans on Rue de Gravilliers in the 3rd district [in eastern Paris], employed Moroccans. They’d put rugs over their shoulders and go door to door, selling them all over the place. There were racist attacks. There were racist attacks. Those employees weren’t Algerian, but the police couldn’t tell the difference. It was really racial profiling. Four or five of my uncle’s 10 employees were thrown into the Seine. Thank God, they hadn’t tied their hands! They managed to swim out; only one died. Afterwards, I found out that there were North Africans whose hands had been tied behind their backs, who had drowned. In any case, I can testify to the terrible violence they suffered, especially from the French state.

“I listened to the news after that night. I understood that there’d been a banned demonstration and that the head of the Paris police had ordered arrests beforehand, to avoid having to disperse it. No further details were given. I didn’t hear anything about that kind of unforgivable violence. All I heard was that people had been arrested.

“The demonstrators weren’t armed. If they had been, they’d have fought back. All the men I saw were pricked with needles to force them onto the buses. If they’d had clubs, they’d have fought back… There were more unofficial deaths – mostly of people drowned – than the killings counted in the official statistics. Those people were washed away by the river; their deaths weren’t recorded.

“There was a kind of segregation at the time. People of North African origin lived in completely different neighbourhoods. It was mainly just men, and they came to work. Algerians and Moroccans lived in hostels; they didn’t even have a working-class suburb. They were outside of our society; it was two worlds apart.

“Sometimes I ask myself if the ordinary French population were afraid of them. But the violence was between the FLN and the MNA [the rival Algerian National Movement founded by Messali Hadj] and against the police.

“Later, when I was 17, I realised the significance of it all. I started reading Le Monde every day; I talked to people about Papon, who had deported Jews from Bordeaux [when he was head of the city’s police during World War II]. I knew then that the police were acting under his orders on October 17, 1961.

“I think humankind is inherently savage and that laws and civilisation are the only things holding it back. If the people responsible for enforcing the law believe they have free reign, then we fall back into savagery. We saw that with genocides, the Nazi barbarism. The responsibility is less with the cops who attacked North Africans that night than with their bosses.

“They took away Papon’s Legion of Honour [upon his conviction for complicity in Nazi crimes against humanity in 1998], but not for October 1961. It is astonishing that de Gaulle – who was certainly not racist – allowed him to stay on as head of the Paris police. It was a hugely important role – a state within the state. And de Gaulle knew full well that Papon was far from a Resistance fighter in the Second World War; that he was a notorious Nazi collaborator.

“Police violence is seldom acknowledged, regardless of the country in which it takes place. It would have been embarrassing to say that the armed branch of the French Republic could have done such things. The police bosses should have been held accountable. That’s what happened with the Vel d’Hiv roundup [the 1942 arrest and deportation of more than 13,000 Jews, including over 4,000 children, to Auschwitz by French police in response to a Nazi request]. There weren’t so many victims on October 17, 1961 – but it’s still unbearable. The idea was to terrorise the North African population so that they’d remain quiescent and that Algeria would remain French.

“It’s still an overlooked chapter in history. I talk about it because I witnessed it; I saw it with my own eyes. I tell people my age, I tell younger people – and none of these people really know about what happened.

“At a protest at Charonne metro station [in eastern Paris] on February 8, 1962, eight people were killed. The following week there was a protest decrying what happened, with perhaps a million people taking to the streets. But for the Algerians who were murdered on October 17, 1961, there was no protest. Nothing.

“It’s one thing that France behaved badly in its colonies, like other European imperial powers. But it’s the fact that France did the same thing at home that’s so shocking. I was just a boy scout on my way home; a scout with certain principles about solidarity. And then I came across a massacre in the middle of Paris, at Place de l’Étoile. Scenes of war, really.

“To acknowledge that 60 years ago, the French state did something unacceptable would be a credit to the current French government.”

‘I had a baby in my arms, I was terrified that he’d be killed’

Djamila Amrane is 87 years old. Her father arrived in France from Algeria in 1914, at the start of World War I, when he was requisitioned for factory work. Amrane became a pro-independence activist after a trip to Algeria.

She went to the October 17 demonstration with her child in her arms. She probably owes their lives to a stranger.

Amrane did not speak about that night until 1987, when she was inspired by the founding of Africa, a feminist, anti-racist NGO in the working-class Parisian suburb of La Courneuve. Since then, she has fought to ensure that the events of October 17, 1961 are not forgotten.

“We weren’t allowed to go outdoors after 6pm. That seemed extraordinary to me because all the Algerians were working in places like the Renault and Citroën car plants on what we’d call the three-eights shifts [three eight-hour shifts in factories that worked 24 hours]. In the evenings the parents did their shopping, the children would play sport. It was terribly unjust for Papon to do that.

“So the French Federation of the FLN called for a peaceful demonstration. They were very keen to ensure it was peaceful; we weren’t allowed to bring so much as a safety pin.

“I was part of a small group of women who travelled to Paris together. We all took our children with us. I went with my son, born the previous July.

“We arrived at Bonne Nouvelle metro station. Unfortunately, as soon as we got there, we were confronted with the police.

“The police beat us and it shocked me. It didn’t matter if you were a woman, if you had a baby with you, if you were a man, whatever. Everybody was separated from the others. Blows would come at you from everywhere. We could hear everything, not knowing who would collapse to the ground. The only question they asked was ‘Can you swim?’ and if you said no, they’d take you and throw you into the Seine.

“I had a baby in my arms, I was terrified that he was going to be killed, that one blow would kill him. He was only a few months old. I must have been completely clueless. It was the madness of youth; I didn’t see the danger. I had this rage within me.

“A woman saved me. She opened this wooden gate, grabbed me by the arm, and took me away – into the hallway of her apartment. ‘What on earth are you doing in the street at this hour with your little brother in your arms?!’ she said. ‘Doesn’t your mum know what’s going on?!’ I told her that the baby was, in fact, my son.

“I can still see that woman with blonde hair; it’s crazy – it’s like she’s right there in front of me. She kept me there for quite some time. If she hadn’t done that, perhaps I wouldn’t be here today to tell you my story. My one regret is that we were so caught up in what was happening that I didn’t ask her name.

“I started wanting Algerian independence when I went there in 1954-55. I was educated; I was already a lot more free than the women I saw there. And I was shocked to see that they were ignorant, they were housekeepers, they were on the lowest rungs of society. They were younger than me. Why weren’t they allowed to go to school? I didn’t understand why that was the case…I couldn’t understand the difference between the little French kids and the bougnoules [a pejorative term for Maghrebians], as they called us. It was a shock to the system. It traumatised me. I thought to myself: If someday there’s some kind of movement, I’ll be part of it. I got involved as soon as I returned to France.

“Many demonstrators were killed [on October 17, 1961]. They never wanted to tell us the number, but we know it was a lot. I have a cousin – he was practically a brother to me because my mum brought him up – we never found him. Two or three days later, we learned at an FLN meeting that many people had gone missing.

“I didn’t talk about what went on that night. Nobody knew. Even my kids didn’t know for years. I didn’t want to go through those scenes anymore. It’s like when you’ve seen a really horrible film – you don’t want to watch it again after that. I must have buried the memory somewhere. It was thanks to Mimouna Hadjam, the head of the NGO, Africa, that it came out. She was talking about it, and I told her I was there. I’d never thought I’d talk about it again – it’s not a nice thing to remember. I could have been killed; my son could have been killed. But in the end, it did me a lot of good to talk about it.

“When I started working with Africa, people often asked me: ‘What is October 17? Is it a date? Is it some kind of day of celebration?’ No, people died on October 17. Others were beaten – taken to a park, I think the Parc de Vincennes [to the east of Paris] – to be beaten.

“People shouldn’t forget what the Germans did to the Jews. They exterminated them. It’s the same with us and October 17, 1961. Above all, I don’t want us to forget what happened. It’s important. This date in history must be remembered.

“Soon it’ll be the 60th anniversary, if you can call it that. I expect the French state to officially recognise that Algerians were killed on October 17 – so that in France, and elsewhere in the world, we can talk about it in schools, because unfortunately it’s not a well-known event.

“People who were there that night get together every year. I don’t do it to be honoured. I’m here right now but I’m not immortal. Soon there’ll be no one left who remembers October 17.

“As I say, I don’t speak to be honoured. Whatever honours I get, I get from my children and my grandchildren, who call me ‘Grandmother Courage’. They’re very proud of me. But I’d like there to be some kind of succession, for these memories to be passed on so that those people didn’t die for nothing. It’s a sad day for us; it shouldn’t be forgotten.”

‘I spent the night in a park’

Mahfoud Rezigat, known as Rahim, was born in the Sétif region in northeastern Algeria in 1940. He crossed the Mediterranean aged 8 years old, along with three older brothers. They went to the city of Saint-Étienne in central France, where their older half-brother ran a hotel. Rezigat joined the FLN; he was arrested in 1958, tortured, and sent to the Larzac and Thol French military internment camps.

He was released in 1961. He was not allowed to stay in the Loire or Rhône region, where Saint-Étienne is located, so he settled in Vanves, a southern Parisian suburb. On October 17, he was on the metro and came across Algerians on the way back from the protest. They warned him not to go to the protest – so he turned around. Several days later, the police came and arrested him at the hotel where he was living. He was taken to the Vincennes detention centre and abused and humiliated there.

Today, Rezigat is president of the APCV, an association that promotes travel and understanding of other cultures, based in Seine-Saint-Denis. He also works to ensure October 17, 1961, has a place in France’s collective memory – notably by speaking about it in secondary schools.

“On October 17, I got back from work in Issy-les-Moulineaux [a suburb just south of Paris] with my friend Saâd and a group of Algerians from the hotel where we lived. It was 5pm. The FLN cell chief asked us to go to Charles-de-Gaulle-Étoile to demonstrate against the curfew. It had been in place since October 5, so all groups of Algerians were forbidden to be out on the street at night. I was often stopped by police.

“The FLN’s instructions were clear: we mustn’t take a gun with us – and we had to be dressed in a way that showed pride in our Algerian identity. That was our state of mind as we set out for the demonstration. We took the metro to Corentin-Celton [just south of Paris]. When we arrived at the Porte-de-Versailles [an entry point to the city from the south], Algerians on their way back from Paris shouted at us: ‘Don’t go!’ The police had already started arresting people.

“We went back to our hotel. It was right in front of Vanves police station…You could see from a distance that police were surrounding the hotel.

“Saâd and I didn’t know what to do. So, we went to the pub and had a drink. We went back to the hotel at 8.30pm, but the police were still there. We had to sleep in Vanves Park, which was just next door. At 6am, we went to work in Issy-les-Moulineaux.

“On Friday, there was a terrible police raid on the hotel. I was by the window. A man was shot as he was doing his ablutions before prayers. He was shot. It was a horrible night.

“The harkis – and I feel no hatred towards them – they were authorised to be very harsh. They’d shout: ‘You want independence? You’ll see, you dirty rebels, you stupid little rats!’ There were insults, there was spitting. They set up a room at the back of the hotel and they’d take everyone they suspected there to be tortured.

“All the hotel’s residents – including me – were taken to the Vincennes detention centre. It was well-known for its very harsh pre-trial detention, before the prisoners were taken somewhere else. There were two lines of police officers, and as we walked between them, they beat us with sticks, kicked us and spat at us. I was small, so I was on the receiving end of rather a lot of abuse. We weren’t allowed to sleep. They’d throw water on us to wake us up.

“The next day, they came and told me I was free to go. I was amazed. I left. They didn’t know I’d spent three years in detention camps, otherwise they wouldn’t have let me go.

“There’d been attacks on the police that August. According to the FLN, they targeted officers who’d tortured Algerians. After that, Papon said: ‘For every policeman killed, we’ll kill ten Algerians’ [“For every blow against us, we’ll fight back with ten”]. It’s also possible that this repression was aimed at squashing the talks between the French government and the FLN.

“Now I expect President [Emmanuel] Macron to officially recognise that October 17 was a state crime and to grant access to the archives. Above all, I hope that on the 60th anniversary of Algeria’s independence next year, he recognises colonialism as a crime against humanity. He said it was [a crime against humanity] when he was a presidential candidate [during the 2017 race].”