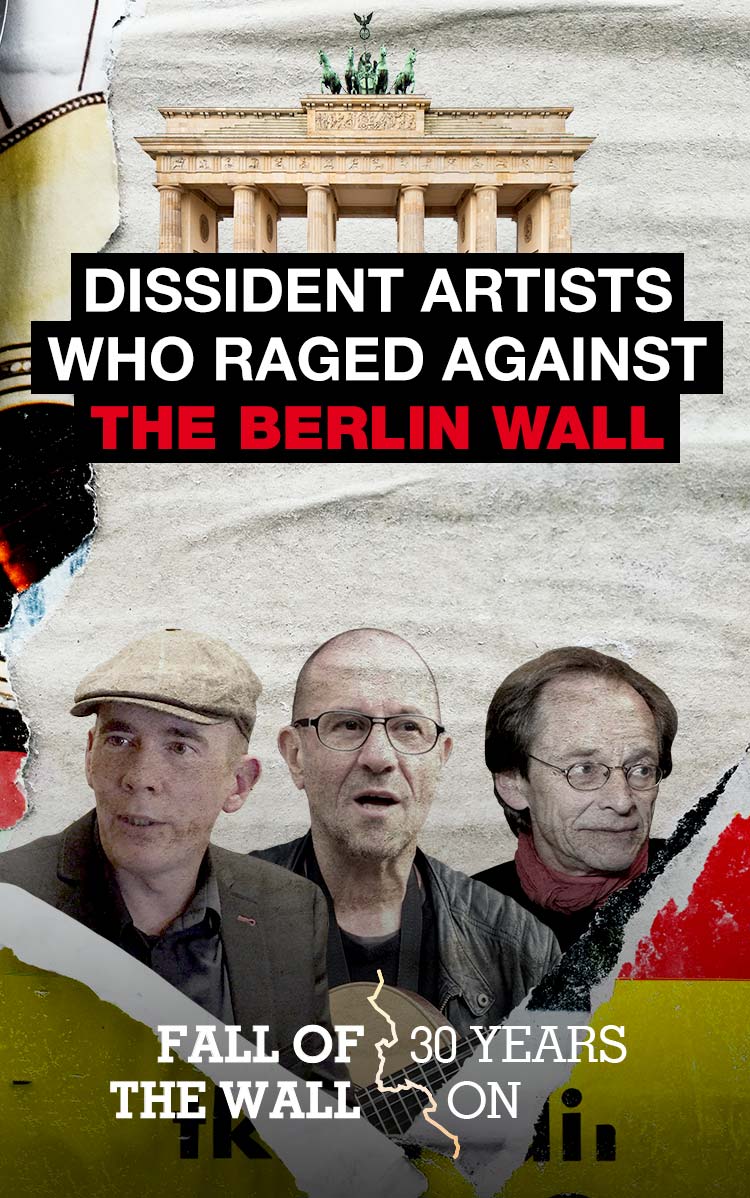

Three well-known East German dissident figures recount their individual forms of opposition against the Communist regime and how the fall of the Wall changed their lives.

One was forced into exile because of his songs. Another was arrested at the age of 14 by the Stasi, the dreaded East German secret police. The third co-founded the only free theatre in what was then the German Democratic Republic (GDR) – to the immense displeasure of the regime.

Stephan Krawczyk, Tim Eisenlohr and Günther Lindner represent three facets of the opposition to the GDR regime. In the 1980s, each one of them, with their own resources, contributed to weakening a regime that was displaying signs of frailty. Speaking to FRANCE 24, the three men described their lives on the fringes of a heavily surveilled society and what the fall of the Berlin Wall meant for them.

In the GDR, singer-songwriter Stephan Krawczyk had a good life. In 1981, the Ministry for Art and Culture awarded him the first prize in the National Song Contest, the highest musical distinction in the country, and Krawczyk had the perks that only a privileged minority enjoyed behind the Iron Curtain.

But three years later, the singer-songwriter began to address "taboo” topics such as the inability to travel and the absence of free speech. Soon, the government took away all his artist’s privileges and prohibited him from doing his job.

"Over time, I thought it was necessary to talk about things that were not right, and the more I talked about these things, the more I was convinced that the situation in the GDR was getting worse and worse," said Krawczyk.

A ban on singing didn't stop him. Krawczyk performed in alternate venues – clubs, churches, schools – "which was new because until then, blacklisted artists did not dare defy the ban”, he explained.

Krawczyk’s reputation allowed him to attract crowds wherever he performed and his uncompromising lyrics "enabled people to approach me and admit that I was saying out loud exactly what they were thinking”, he said.

From being a star of the regime, Krawczyk became a dissident star. This was unacceptable in the eyes of the regime, who allegedly tried to kill him and his wife, the famous director and civil rights activist, Freya Klier. "One day, while we were in the car and my wife was driving, she started screaming, gesticulating and banging her head against the window. If I hadn't managed to straighten the steering wheel, we would have been finished,” said the musician. The couple is believed to have suffered from a nerve gas attack from the wheel-side car door due to which, Klier suffered delusions and narrowly escaped crashing into a tree.

In January 1988, the Stasi arrested Krawczyk and his wife. He was given a choice: exile or 12 years in prison. "If my wife hadn’t received the same sentence, I might have opted for prison because I didn't want to leave East Germany. “We wanted to change the system from within," he explained.

When the couple first arrived in West Germany, it was a shock for Krawczyk. The dissident musician was welcomed as a hero, featured on the front page of the leading German weekly, Der Spiegel and the New York Times. "I played to a full house during my first concerts because people wanted to see the musician who was on television in person, I suppose," he recounted with a smile.

But Krawczyk quickly grew tired of the "media circus". He decided to take advantage of his new freedom "to discover the world, sing in Canada, and sail with a good friend because, at 33, I had never seen the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean.”

At 63, Krawczyk’s transition to democracy has not always been easy, and at times he criticizes Western "consumerist” society. But he has no sympathy for “ostalgie” – a term fusing the German ost for “east” and “nostalgia” that describes a yearning for some aspects of life in the GDR. "I knew in my bones what a dictatorship was, and those who now say it was, in the end, a rule of law, have forgotten how the regime trampled on the souls of its people.”

With a flat cap perched on his head, Tim Eisenlohr, 46, looks like the eternal rebel. Sitting in the former Stasi premises, now the archives of the East German secret police, he recounted how he became the youngest actor in one of the most significant events of the twilight of the Communist regime.

At 14, Eisenlohr had already started questioning the system, asking his teachers uncomfortable questions that got him sidelined in school. Instead of joining Communist youth organisations like his comrades, Eisenlohr started hanging around an Evangelical church which, because of its special status in the country, attracted citizens who had broken with the regime. That’s when he learned about the existence of the "Umwelt-bibliothek" (literally, environmental library), a church movement that developed into an important centre of opposition against the regime in the 1980s. Eisenlohr became one of its youngest and most assiduous members.

Attached to the Protestant Church of Zion in Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg district, this library was the main meeting spot for the opposition in East Berlin. "The image is a bit far-fetched, but it was a bit like the Wikipedia of the time because this library had banned books – such as Alexander Solzhenitsin's "Gulag Archipelago" – that foreign journalists and diplomats were illegally bringing into the country," Eisenlohr explained. There was also a gallery where censored artists could exhibit their work and a regular Samizdat magazine was also published.

On the night of November 24-25 1987, the Stasi decided to end the Umwelt-bibliothek. But the raid on the premises was poorly organised, and the police did not find what they were looking for, including banned periodicals. Despite this, Stasi officers arrested the people at the premises and that’s how Eisenlohr became one of the Stasi’s youngest prisoners. He would stay in Stasi detention for only six hours and Eisenlohr maintains the experience failed to traumatise him. "They played good cop-bad cop with me, which didn't impress me much," he said.

For the regime, the Umwelt-bibliothek raid was a disaster. "We were in the midst of international relaxation, and all eyes were on East Berlin. The images went around the world, demonstrations of support were organised and for all of us – who were only known in opposition circles – it was a huge publicity stunt. Above all, it sent a strong signal to citizens: the Stasi did not succeed in shutting down an opposition centre, whereas before it could have done so without any problem," he explained.

Eisenlohr spent the final hours of the GDR as a young resistance hero, ready to brave the Stasi. After the fall of the Wall, he initially enjoyed the freedom for which he had fought so hard, even isolating himself for nearly 10 years on an island in northern Germany to take care of horses. But in 2015, the refugee crisis woke up the activist in him that had been lying dormant for decades. He then co-founded the NGO, Resco International, which helps Syrians trying to reach Europe and has visited the Greek island of Lesbos several times to understand the scale of the crisis.

Today, it’s a trendy café in Berlin’s Prenzlauer-Berg district. But before the fall of the Wall, the Zinnober Theatre was the only free theatre in the GDR. It was co-founded by Günther Lindner, a puppeteer who did not want the regime to pull the strings of culture alone.

"In the GDR, theatres were run by the authorities. But what we wanted to do was to create our own productions, to reinterpret myths and legends in the light of our own experience in East Germany," explained the artist, now 71. The Zinnober Theatre was founded in 1980 without any legal framework.

"The problem was that for the authorities, we didn't exist. We could perform our plays, but not on our premises. We had to find other theatres that agreed to lend us their rooms. But we also played in churches or cultural centres," he recalled.

This freedom was a grain of sand in the gears of the regime. It also made the Zinnober Theatre famous. "Wherever we played, we were packed, without having to advertise," said Lindner. The Stasi also attended each performance.

But the government didn't know how to stop something that didn't exist legally. Especially since the creations of the Zinnober Theatre did not overtly criticise the regime. "They were not political pieces. It was our existence that was political," explained the puppeteer.

In 1988, under pressure from influential state artists, the authorities even recognised the Zinnober Theatre. One year before the fall of the Wall, Lindner and his company won. They were allowed to perform abroad.

The fall of the Berlin Wall allowed Lindner and his theatre mates, for the first time, to perform in their own premises. A few years later, they changed their name to Theatre o.N. But the post-GDR period was hard for Lindner and his theatre colleagues. "Suddenly we were no longer the only free theatre, we had to fight to attract audiences," he explained, displaying a certain nostalgia for the Communist era. With the market economy, Lindner had to learn what he calls "the dictatorship of audience taste". During the GDR days, "We could create what we wanted. Now we have to take into account what people want to see if we want to be able to pay the bills," he noted ruefully. If, in the former East Germany, freedom had a price, in reunified Germany, Lindner has to foot the bill.