For more than a year, the Aquarius – a former fishing boat – has been cruising the Libyan coast searching for the thousands of migrants who attempt the crossing to Italy every day. Our reporter spent 10 days on board with the humanitarian workers who are on the front line of rescue operations.

It takes two days for the migrant crisis to come and hit us full on, for the first time.

At first we don’t realise it’s happening. We spot something about a hundred metres away, but it looks like crates, or maybe a wooden plank. Later, we see what we don’t want to see—a body floating in the water, arms outstretched in the shape of a cross, motionless except for the undulations of waves underneath. Mary-Jo, a nurse with MSF, takes charge. “Stay on the other side of the boat,” she warns. “There’s something in the water that will be hard to witness.”

Mary-Jo is no stranger to death. Three years earlier in the Central African Republic “MJ”, as she’s known to her teammates, miraculously survived an attack by ex-members of the Seleka militia on the hospital of Boguila, in the northeast of the country.

“It was April 28th, I heard shots. I don’t really know how the sequence of events played out. I hid behind a wall…when everything stopped, I looked up and saw bodies littered around me,” she explains, somberly, soberly, without taking her eyes off the sea. MSF lost three of its personnel that day. Thirteen others died as well.

But Mary-Jo still can’t get used to the sight of bodies floating in the Mediterranean. Some people can, she can’t. Another rescue ship, the Vos Hestia, from the NGO Save the Children, will ultimately pick up the body. Unlike the Aquarius, it has a refrigerated morgue on board.

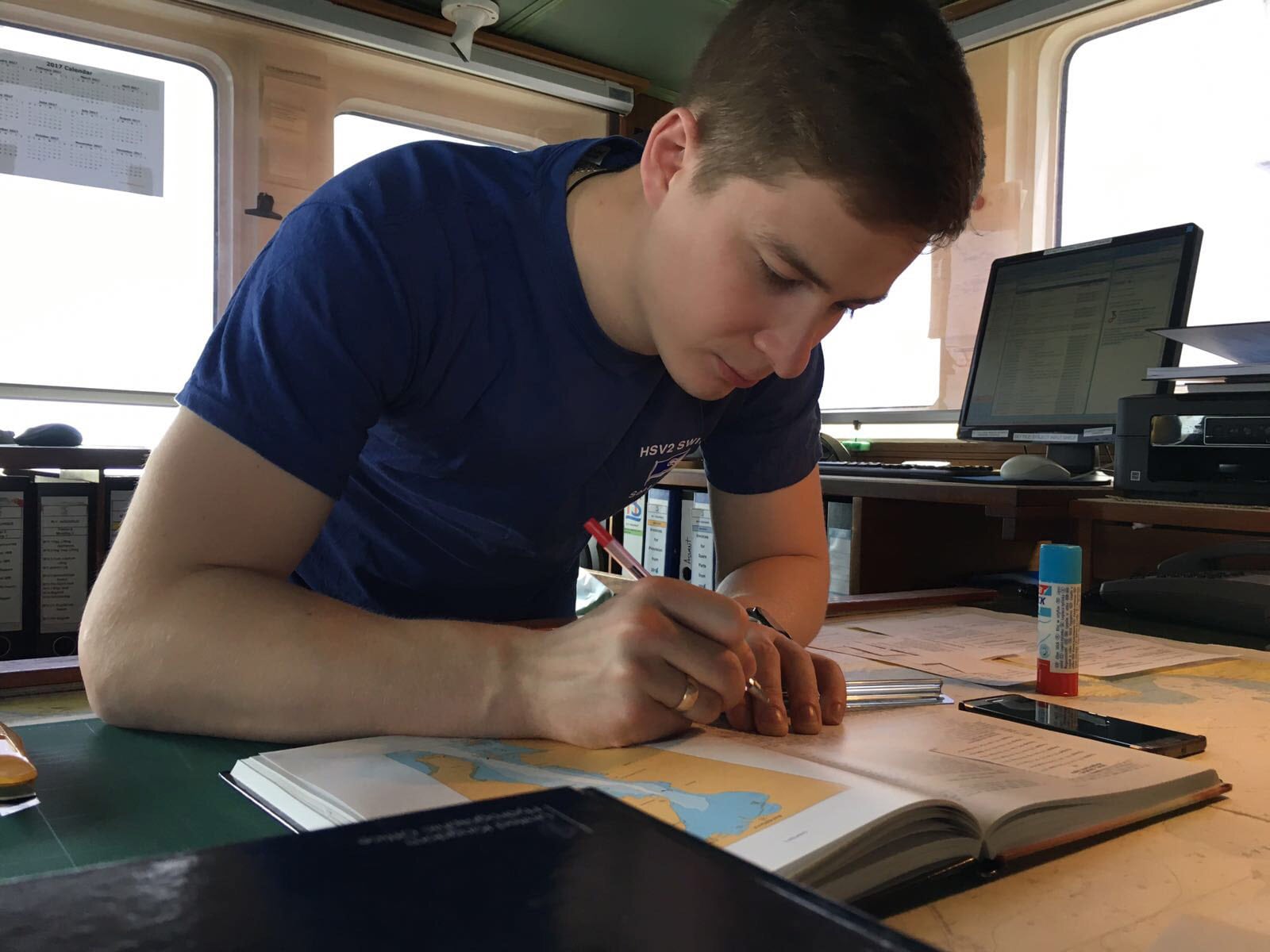

By now, the Aquarius has been in the SAR zone for days, and a certain routine has set in among the crew. But with new rules tacked on to the old ones. At 6:30pm, we lock the ship’s doors. A precaution against a possible – if uncommon – boarding by Libyans. Although piracy is rare, it’s still a possibility, and the team isn’t taking any risks.

It’s still morning though, and the doors are wide open. The teams from MSF and SOS Méditerranée are just getting out of their meeting. “The meteorological conditions aren’t great, but there’s a ‘window’ opening up at night,” Marcella explains. The horizon is blank and motionless. The sea is calm, and the sun is blinding. Very different from the day before, when waves snarled at the ship.

“It’s strange,” interjects Nicholas, a member of the SAR team who is next to us on the bridge, smoking. “Usually there are Libyan fishing boats out. I don’t understand why there’s still nobody on the water.” The Aquarius doesn’t always know what’s happening in real time in Libya. Is there fighting not far from Tripoli? A national holiday that has kept the fisherman onshore? At any rate, the ship never approaches the Libyan coast, because it’s not authorised to enter Libya’s territorial waters past 20 km from the shoreline.

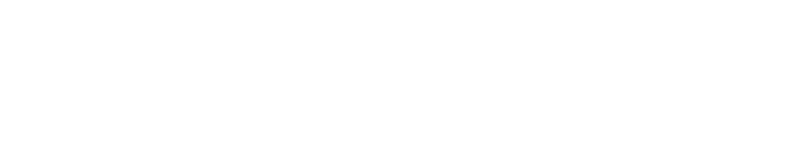

On the bridge, the highest vantage point on the ship, Operation Sea Watch is on its third day. Every hour and a half, from sunrise to sunset, the SOS Méditerranée team scrutinises the seas in front of, behind, and to either side of the ship using specialised long-distance binoculars. They are assisted by the ship’s radar, which also scans the “rescue zone.” In just a few days, we learn to decipher the information it reveals. A long streak on the screen might be a migrant dinghy, a large wave, a fishing boat…

The Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC), a maritime traffic control body based in Rome and supervised by the Italian Transportation Ministry, supports the Aquarius’s search mission. The MRCC sometimes directly contacts humanitarian rescue ships and transmits the location of a boat in distress within its vicinity and asks them to come to its aid. The MRCC is the ultimate authority on board. The Aquarius never launches a rescue operation without first running it past Rome. And when multiple humanitarian boats (Sea Watch, Vox Hestia, Luventa…) arrive in the same zone at the same time, the Italian authorities are the ones who map out how they are supposed to proceed.

Fifteen seconds, that could save a life.

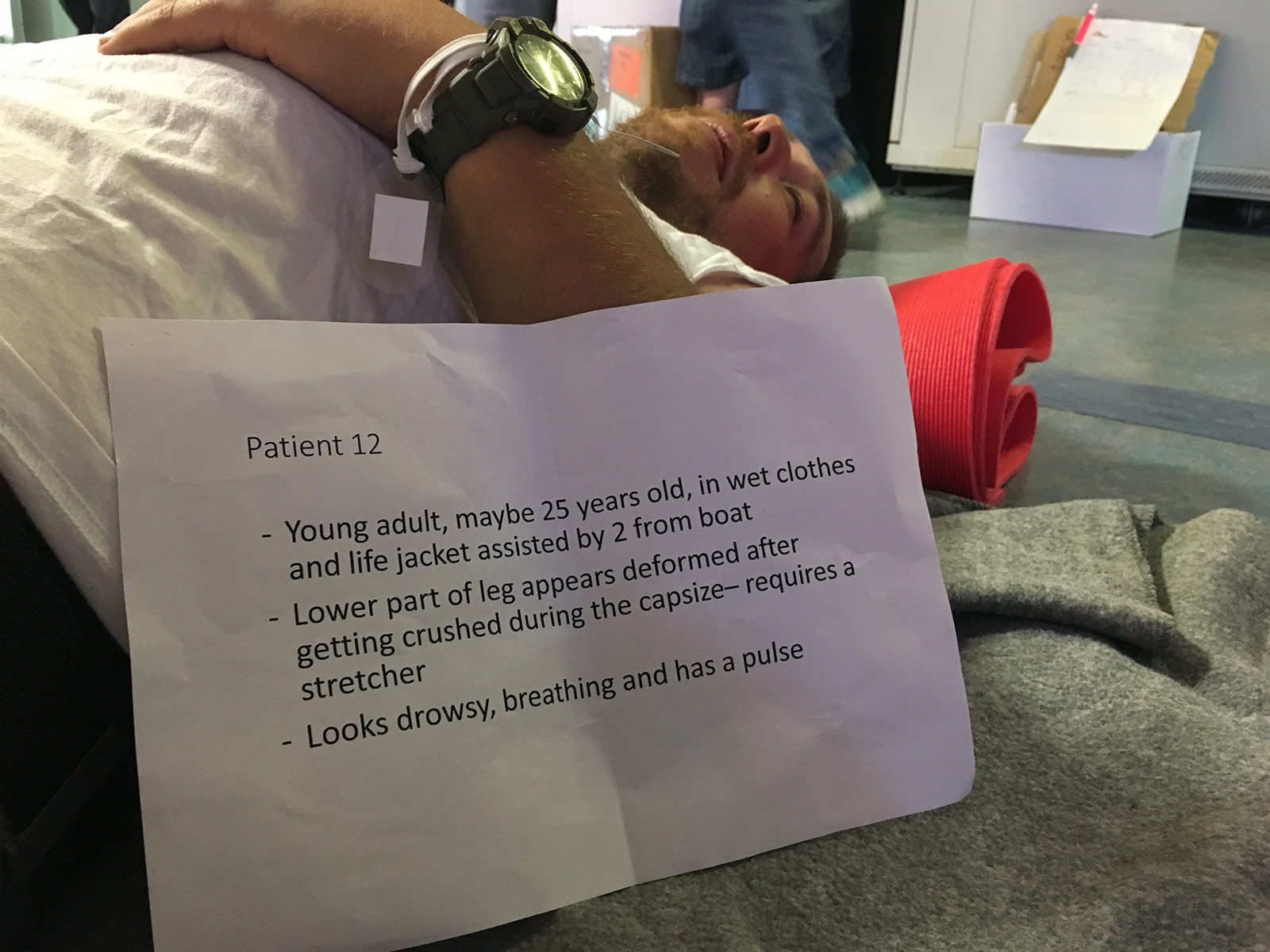

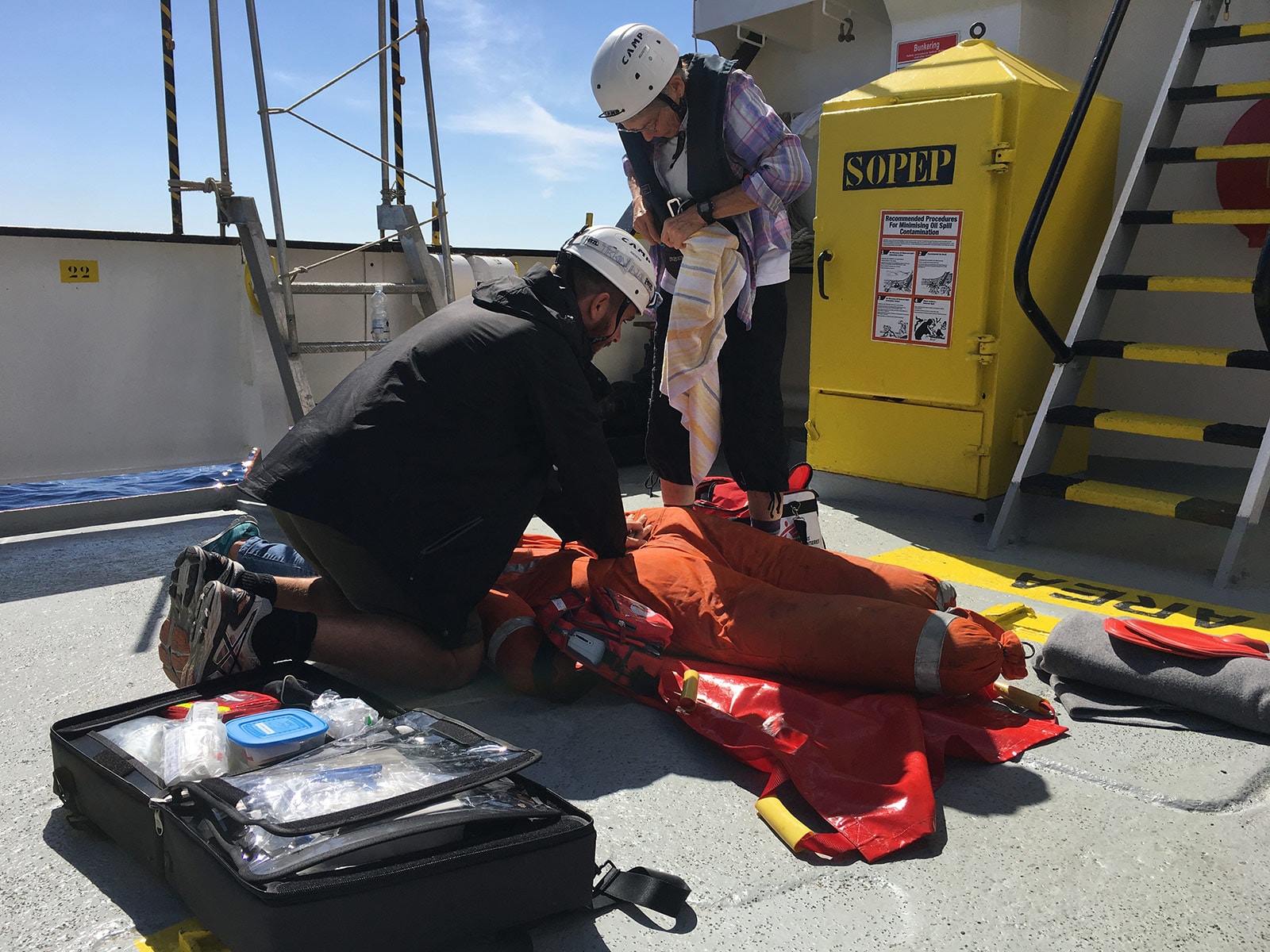

It’s one o’clock now. The SAR teams are training while they wait for a new rescue operation. Each team member goes through the motions of a rescue at least a hundred times, but they’ve stopped actively counting. Today, they’re simulating a “Mass Casualty Plan,” which would be activated if more than two people fell overboard into the water. They practise resuscitation, moving severely injured people, immobilising broken limbs, helping someone who can’t stand upright, and basic first aid. Nicholas plays the role of an unconscious pregnant woman, Anthony takes on that of a 25-year-old man with two broken legs, Mary simulates a heart attack, and Till becomes a terrified woman with signs of hypothermia.

“We practise the same exercises over and over so that we can get more efficient at dealing with them,” explains Bene, the ship’s “deck leader,” which means that he coordinates operations on the bridge during a rescue. “The first time, it took us 45 seconds to transport a body from the Zodiac to the doctor. The second time, 30 seconds. Fifteen seconds could save a life.”

During a rescue exercise, each team member plays the role of someone in need. Here, Anthony is a 25-year-old man with two broken legs. © InfoMigrants

During a rescue exercise, each team member plays the role of someone in need. Here, Anthony is a 25-year-old man with two broken legs. © InfoMigrants Two members of the SAR team, Tanguy (left) and Anthony (right) build a new berth for one of the Zodiacs. © InfoMigrants

Two members of the SAR team, Tanguy (left) and Anthony (right) build a new berth for one of the Zodiacs. © InfoMigrants Elizabeth (standing) and Connor, the MSF doctor, simulate CPR on a mannequin. © InfoMigrants

Elizabeth (standing) and Connor, the MSF doctor, simulate CPR on a mannequin. © InfoMigrants Every day from sunrise to sunset teams from SOS Méditerranée scan the horizon for signs of migrant dinghies. © InfoMigrants

Every day from sunrise to sunset teams from SOS Méditerranée scan the horizon for signs of migrant dinghies. © InfoMigrants The full MSF team. © InfoMigrants

The full MSF team. © InfoMigrants

Connor, the doctor from MSF, suggests a new exercise—giving CPR and placing a body in a recovery position in an emergency situation. Everyone is invited to participate, including journalists. “You’re here doing your job, which is fine, but if you ever need to help us, then it’s better that you know what to do,” Bene says. I put down my camera, notebook, pen, and drop to my hands and knees, a helmet on my head and a life vest around my neck, next to a mannequin that someone is urging me to save. My movements are clumsy, so I start over, and then repeat the process again.

When they aren’t training, the team isn’t just sitting around: they play sports, clean; tinker with things, paint, repair stuff, build new stuff. In six days, Anthony created a “new berth” for the Zodiac tasked with approaching migrant boats. Tanguy, Max, Mary, and Till sorted and labeled all of the life vests. Elizabeth, the midwife, cleaned the “shelter,” organised pacifiers for babies, and sorted clothing kits by age.

The next day, the wind picked up. And two wooden dinghies came into view.