© Kenny Karpov - SOS Méditerranée

For more than a year, the Aquarius – a former fishing boat – has been cruising the Libyan coast searching for the thousands of migrants who attempt the crossing to Italy every day. Our reporter spent 10 days on board with the humanitarian workers who are on the front line of rescue operations.

I look at his feet, his ankles, his thighs, worn so thin by the strain of saltwater and exile. I look at his thighs, and then down at my own. I wonder if he’ll be able to pull himself out of the lifeboat without breaking his legs. There’s no way such thin legs can carry the weight of his body. I don’t know his name. The noise of the outboard motor driving us through sea spray towards the Aquarius drowns out the sound of his voice.

I don’t have my camera with me, because the presence of Libyan coastguards in the rescue area means we have to be extra cautious. But the Sudanese man is lying sprawled on the dinghy’s surface, clutching his arms around his body. His shorts are soaked. Its thirty degrees Celsius, but he’s shivering. Another man—a friend, his brother, or maybe just an unknown companion in misfortune—puts a hand on his shoulder.

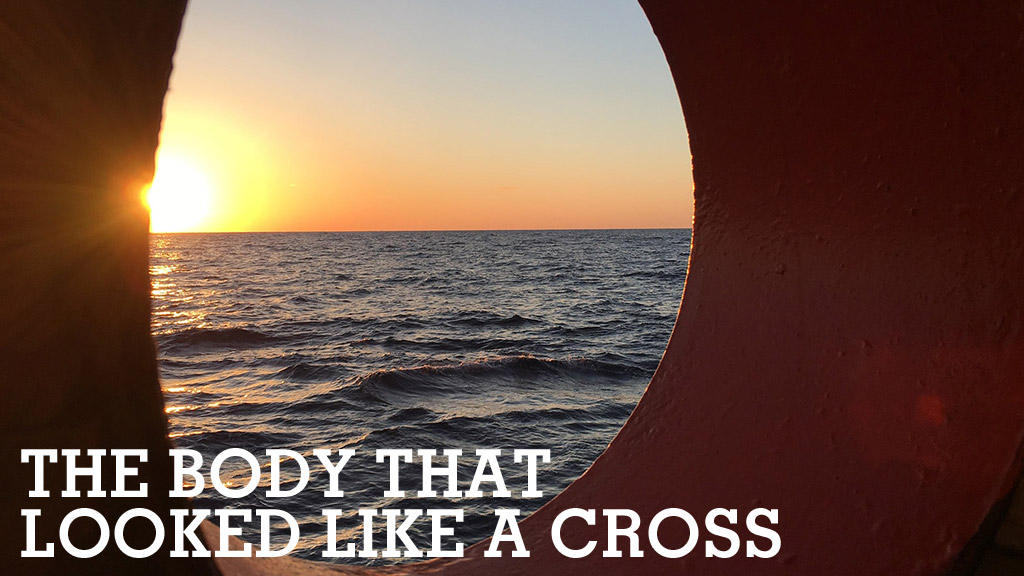

Their bodies look almost indistinguishable from each other. Where was he headed, adrift in this vast expanse of sea? Did he really think he was going to reach Europe’s coast in a wooden boat barely able to take him out of Libyan waters? It’s been years since a dinghy last made it to Italian shores. The Aquarius comes alongside the small, wooden boat, lowers a ladder, and rescuers stretch out their hands. It’s half past noon, and the Aquarius has 92 rescued migrants on board. Less than three hours later, they will number 187.

The warning had come in at 12:00pm. “Two wooden boats have been spotted,” Ebe, one of the crew members, told me as I was smoking a cigarette on the bridge. “Go and get ready.”

The two vessels, laden with a single dream—Europe—had left Libya at 5:00am that morning, when the sun’s first rays illuminated the route, and while the disappearing night obscured the rowboats from the view of the coastguard. It took them seven hours to cross paths with the Aquarius.

I get hurried along towards one of the ship’s Zodiacs, the speedboats whose task it is to pull alongside migrant vessels floundering at sea. We have to move quickly—the first of the two wooden crafts is carrying too much weight, and is at risk of sinking. An initial team of rescuers cries out as we approach, “We’re from an NGO, we’re here to help you, ok? We aren’t Libyan; don’t worry.”

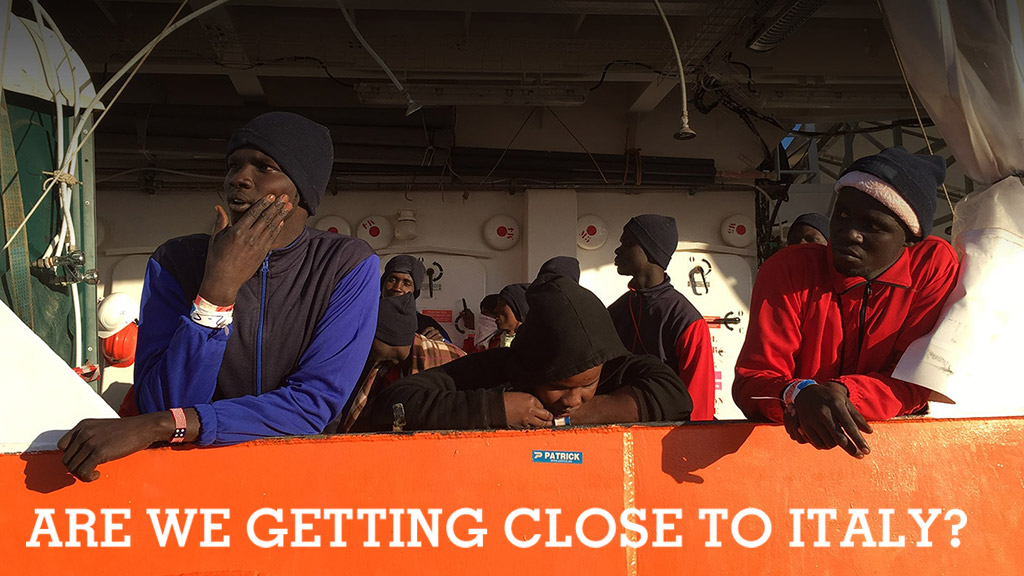

They shout in English first, and then in French and Arabic, attempting to reassure the migrants on the boat. Panic could lead to people falling overboard, into the water. “It will be alright, ok? We are going to take you to Italy, stay calm.”

There are fifty people in the first wooden boat, all of whom look haggard. The rescuers begin to distribute life vests, talking severely to those in the boat. “Stay seated, ok? If you stand up, we will stop everything!” I can’t tell if they understand, but they don’t move. “We’re going to get you out of here, but first you have to tell us if there are children, or injured people here.” There’s no answer. Nobody reacts, their eyes don’t leave the outstretched hands of the rescuers. I look at the water, a morbid curiosity pushing me to scan the surface for bodies.

It’s four o’clock. The 187 shipwrecked people are on board the Aquarius. Tanguy, a rescuer from Brittany with the aid group SOS Méditerranée, jumps on the boat, now empty of its human cargo. He peers into every corner, making sure that there are no forgotten bodies anywhere. We often think about those who drown, but there are also those who suffocate, those who, in a moment of panic, die crushed under the weight of their neighbours. They are generally found in the nooks and crannies of boats, at the end of rescue missions. Once the final inspection is done, the boats are usually sunk, so that they can’t be used again.

Today, only one dinghy will be sent to the depths of the Mediterranean—the two others will be burned. In a sort of ritual that only they could explain, the Libyan coastguards set fire to the boats after evacuating the migrants inside. The presence of the soldiers, outside of Libyan waters, is rare. The humanitarian workers, who are wary of their “sometimes unpredictable” behaviour, don’t communicate with them.

We watch the thick, black smoke climb slowly into the upper reaches of the sky. It’s 4:30pm by the time I get back onto the rescue ship, with a heavy heart. Thirty minutes on the Zodiac, and I’m worn out. The swell of the sea, the waves, the sun. I don’t see the Sudanese man anywhere, I don’t know what he looks like. I never saw his face. I only remember his legs.

On board, there is none of the chaos I expected to find. Amid the hundreds of bodies numbed by the hardships of their journey and the cries of children, SOS Méditerranée and Médécins Sans Frontières (MSF – or “Doctors Without Borders”) manage and direct the situation. Rules are the key to living together in this confined space, they explain. After distributing kits (each migrant receives a blanket, a bottle of water, and clean clothes) the most vulnerable people—women and children—are taken to a space called the “shelter,” while men are sent towards the ship’s stern. Husbands are separated from wives, brothers from sisters, fathers from daughters and sons. They will find each other again later, in the evening, before leaving one another again for the night.

I head towards the “shelter” where a dozen people are stripping off their soaked clothing. At the entrance, a photographer from MSF and Mark, from the medical team, are gently pushed back by Elizabeth, a midwife. There are no men allowed in the “shelter”, a measure put in place to allow women to rest away from the presence of potential predators. I give an eight-year-old boy a pair of pants marked “12-year-old.” I don’t know where the six-year-old size is stored. I hand out extra polar blankets, even though it’s forty degrees inside the room.

I had promised the team that I would put down my camera and notepad to lend a hand, but I’m rapidly confronted with my uselessness. I’m not a sailor, so I can’t help with sea manoeuvres; I’m not a nurse, I’m just an obstacle in the path of the medical team that’s hurrying to and fro; I don’t speak Arabic so I can barely speak with most of the families here. I try to take four Syrian children to the bathroom, which quickly becomes a fiasco. I’m also at risk of flouting the rules—I’m on the verge of handing out cigarettes, which is strictly forbidden, to two men who saw me smoke, and tempted to give the Wi-Fi password, which is also against the rules, to a Syrian mother who wants to send an email to her own mother, who she left behind in Syria.

Dinnertime is at 5:30pm. I start speaking to some of the rescued migrants. They come from Syria, Bangladesh, Sudan, Morocco, Nigeria, Togo and Niger. Their stories have much in common; hell in Libya, getting beaten by militiamen, gunfire, sometimes torture, and being packed body by body into rickety wooden boats before being launched into the sea by unscrupulous smugglers. Certain stories provoke only horror and disbelief: slave markets, migrants shot in the head for no reason.

Before long, I’m surprising myself by not asking questions anymore, but rather trying to find words that might comfort and reassure. My eyes meet those of Albara, a 15-year-old Sudanese boy who is sitting on a bench. He’s not crying or complaining, but he’s not speaking either. At the sound of the word “Libya” he puts his head between his hands and holds it there for a few long seconds. When I go up to him, he takes my hand and holds it in his. I don’t try to interview him, instead I look at him and imagine him drowning in the middle of the Mediterranean. How many boys like him have just disappeared beneath the waves? I tell him that now, everything will be alright.

“No,” he says, and then he turns and walks away to lie down, close his eyes, and sleep.