Video: the investigation

Video: the investigation

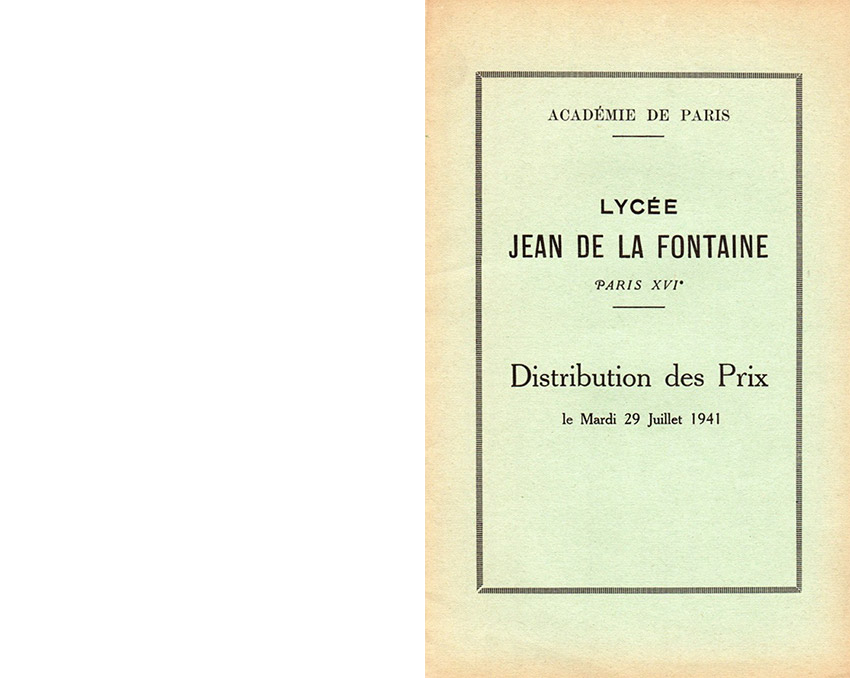

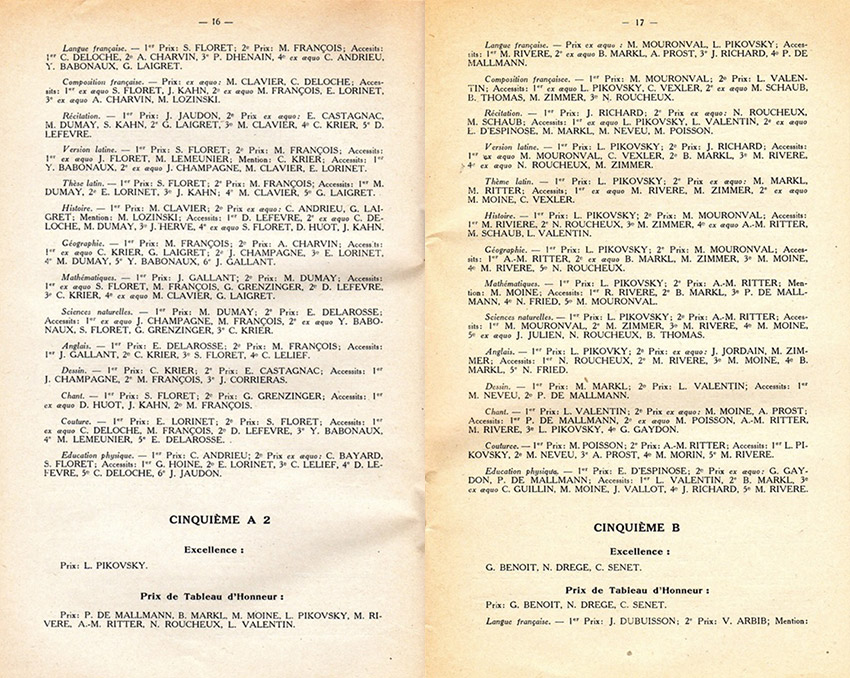

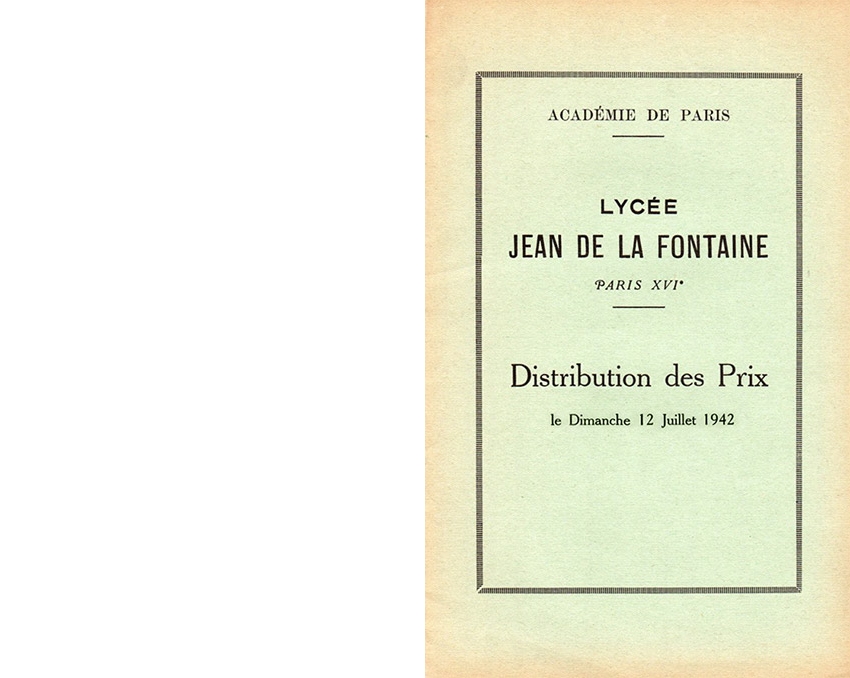

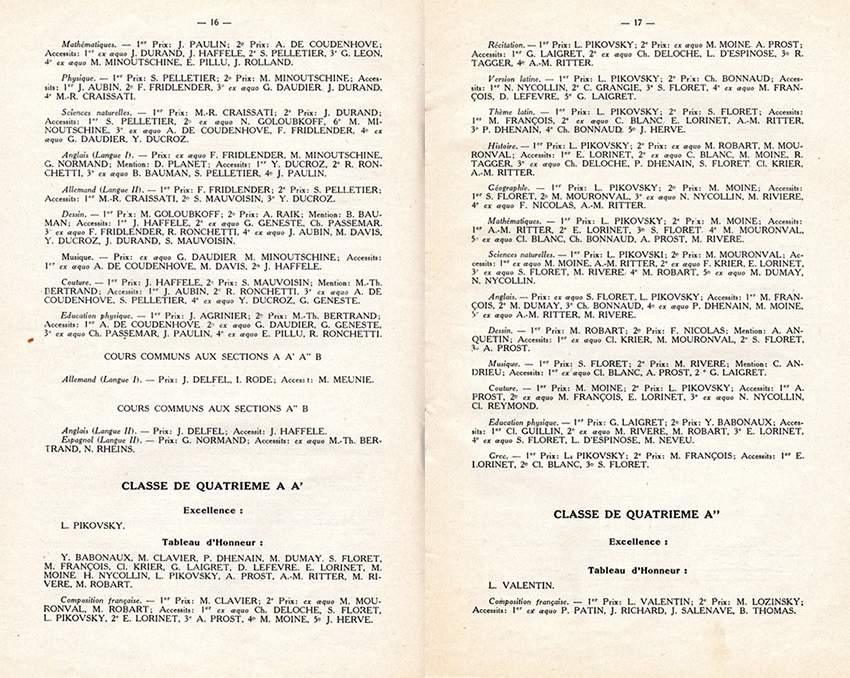

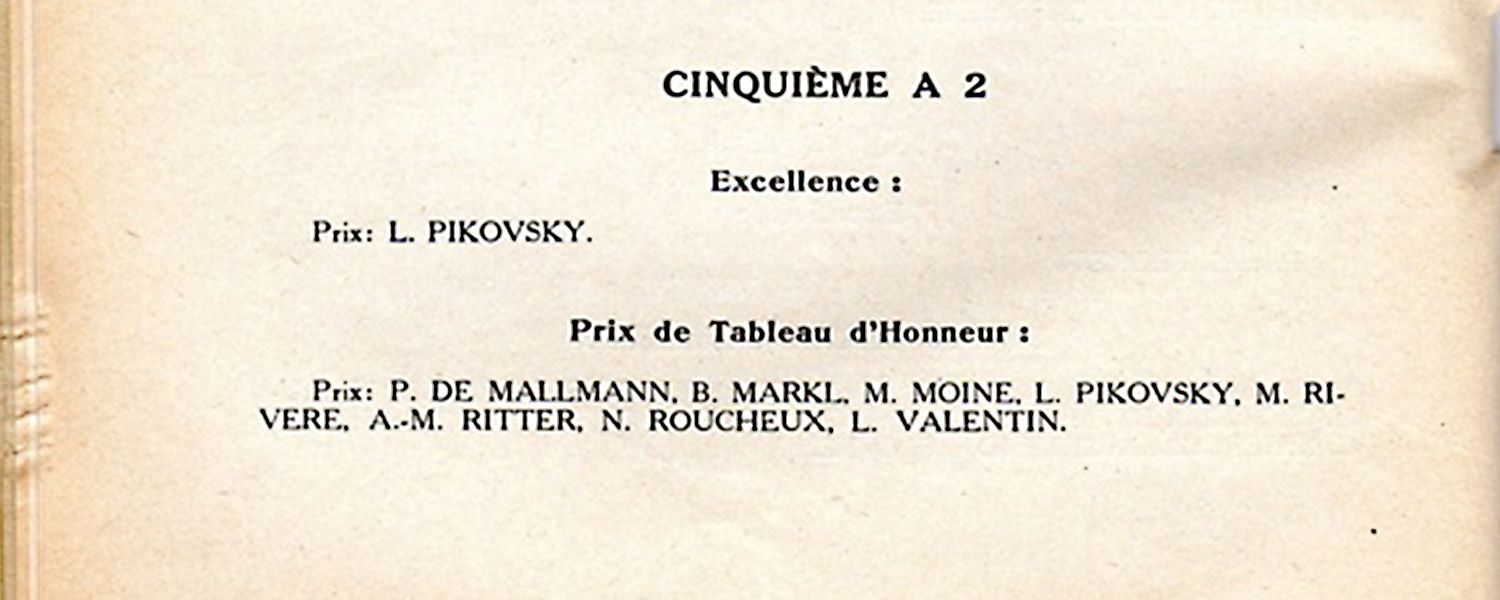

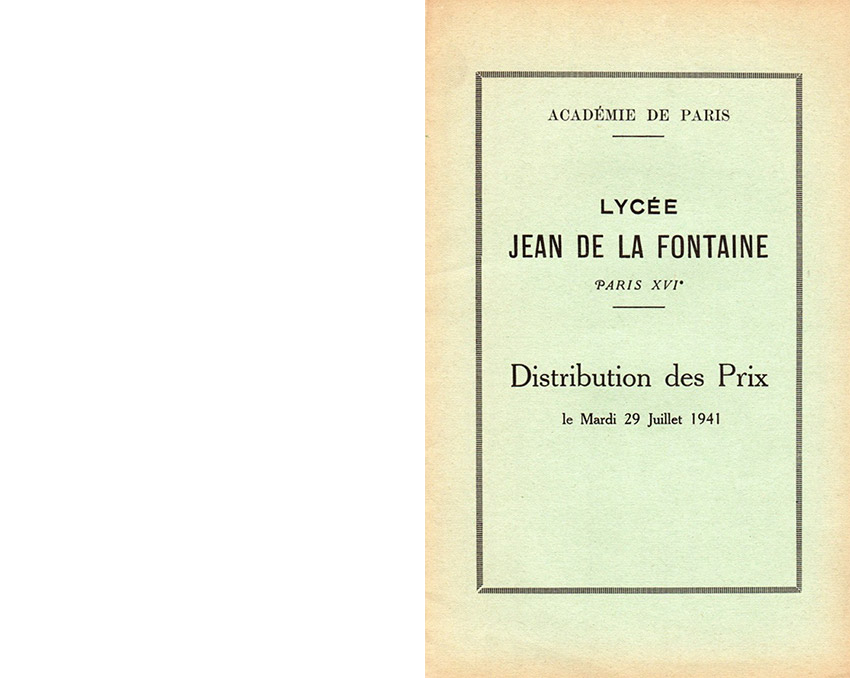

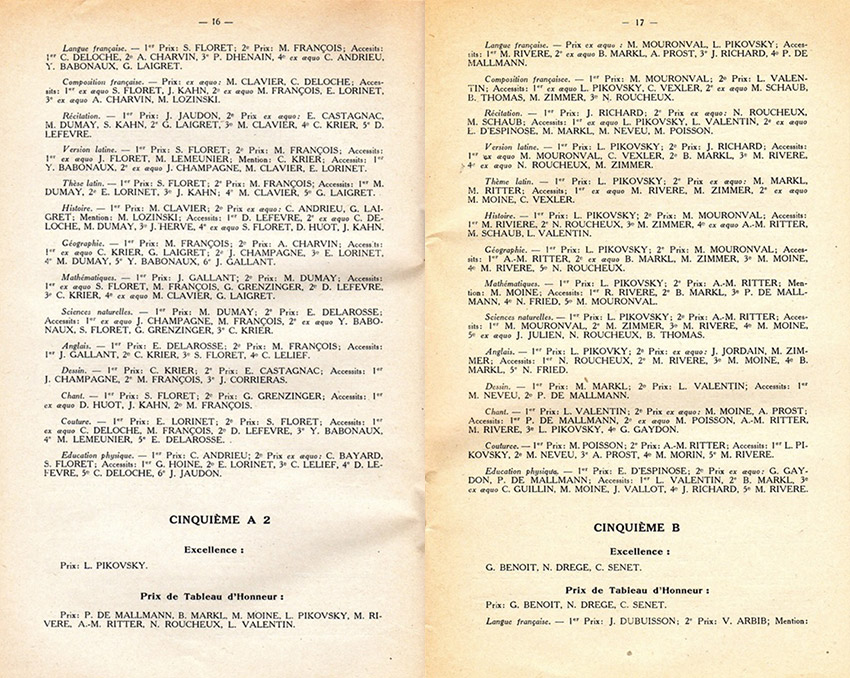

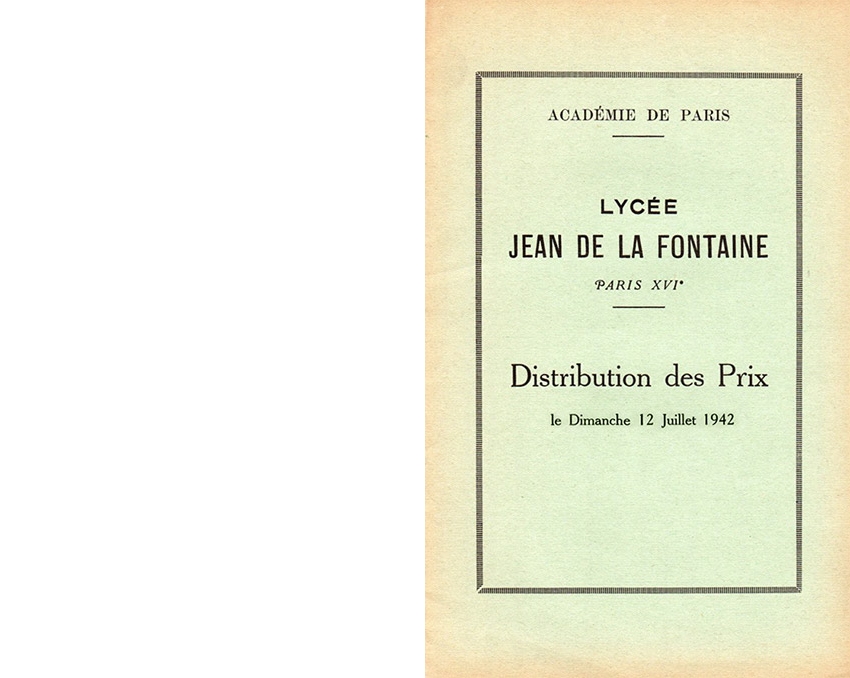

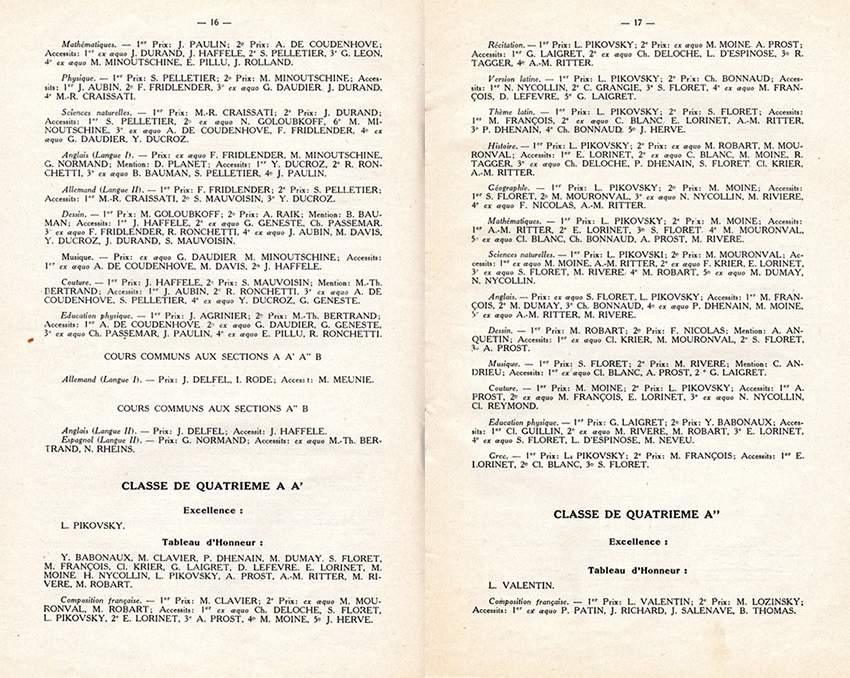

Louise’s satchel was not found in the old school cupboard. Miss Malingrey’s nephew, her only surviving relative, says he has no idea where it could be. But other documents, including the school yearbooks, offer some insight into Louise’s time at the all-girls institute she attended. During the 1940-41 school year she was top of the class in almost every subject: French, Latin to French translation, French to Latin translation, History, Geography, Maths, Natural Sciences and English. She was rewarded with the Prize of Excellence, and continued to be a star pupil the following year, winning the First Prize in Greek.

The yearbook from the 1942-43 school year has disappeared, but an intriguing essay survives. Louise had to answer a question about the start of the war three years earlier: “You were small during the exodus [of 1940, when up to a quarter of the French population fled the country’s north as German forces invaded]. If you had been the same age as you are now and were allowed to take one book with you, what would it be?” The fifteen-year-old answered, philosophically: “Such a book would have to distract to the extent that I forget all the horrors of life and am filled with courage. It should help shape my character. And, above all, I must never tire of reading it again. Which book could offer me that? I can only imagine a prayer book in French (…) When the Earth falls victim to horrific carnage and men cause such sadness, where else can you find refuge if not in God? I would indeed bring a translated book of prayers if, through the goodwill of those who force me to flee my nest, I were allowed to take my favourite book along.”

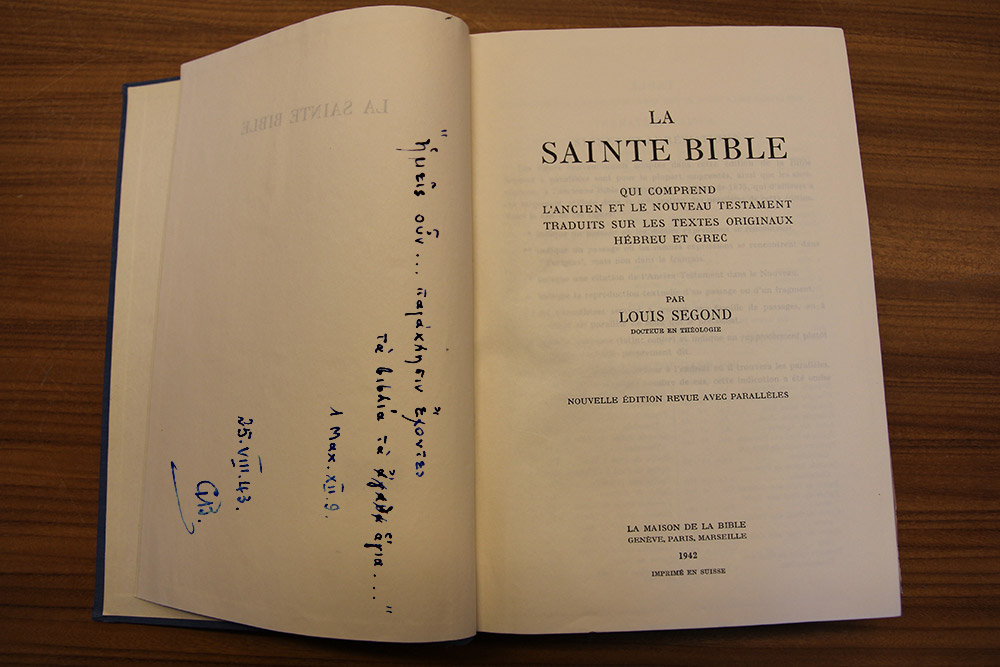

The day she was arrested, Louise left a Bible at Miss Malingrey’s house. It contained a short dedication written in Greek and dated August 25, 1943. An extract of Jewish writings from the Books of the Maccabees, it reads: “For consolation, we have the holy books which are in our hands.” But she did not take this source of consolation on her final journey. Perhaps she knew the men who drove her from her “nest” would never let her read again.

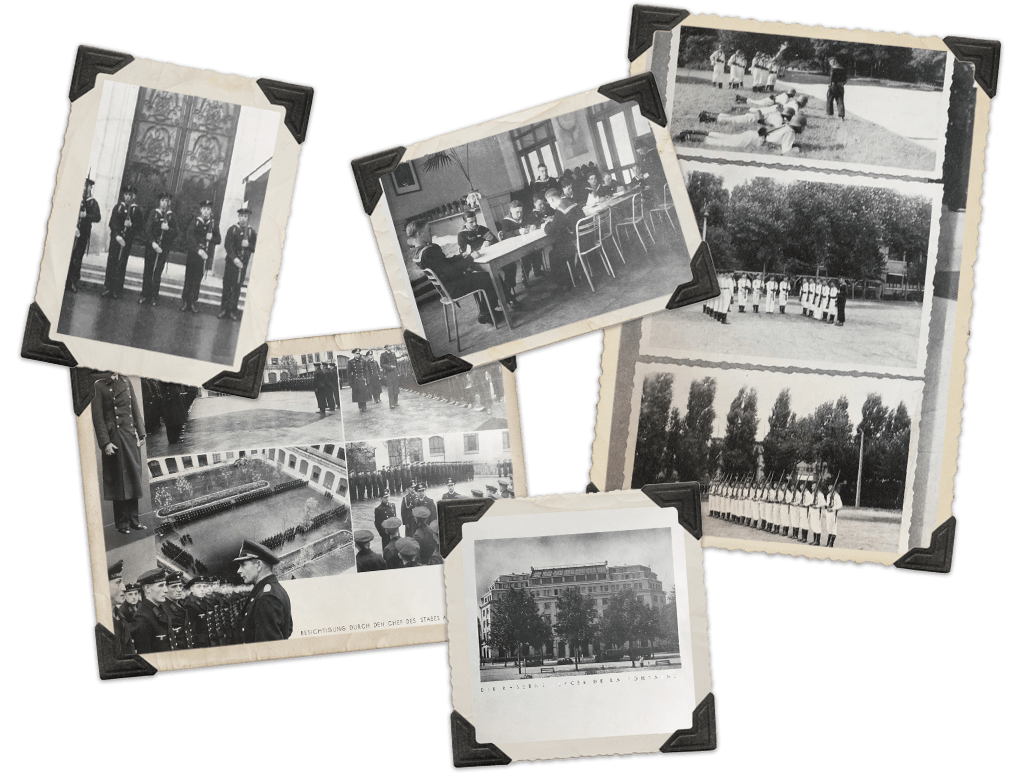

We decided we needed to track down Louise’s fellow classmates to help paint a fuller picture of the young pupil. We were unable to find the class registers from the war years and could only conclude that they have disappeared. Instead, we turned to the school’s awards records and found the identities of some of Louise’s contemporaries, listed under their maiden names. Thanks to genealogy websites, phone directories and a few lucky clicks online, we were able to make some contacts over the phone. The elderly women, most of them in their nineties, could hardly believe what they were hearing. “It’s been more than sixty years since anyone called me by my maiden name. How did you find me?” exclaimed Yvonne Ducroz. She was in the year above Louise and did not know her. But she was able to tell us what school was like during the Nazi Occupation of Paris. “I only studied for one year in the Jean de La Fontaine building because the Germans requisitioned it as a base for the German Navy. We had to move to Janson de Sailly,” she said. The school’s fiftieth anniversary booklet confirms her account. In October 1940, the occupying Nazi forces established navy offices in what was then a brand-new building, inaugurated two years earlier. Until 1945, the pupils took classes at a local school called Janson de Sailly.

During the Occupation, restrictions affected many aspects of Parisians’ daily life. “We were deprived of a lot of things,” said Yvonne. “The heating was minimal. We were cold in winter, but when you’re fourteen you’re young, you still have a zest for life despite the sadness of what’s happening around you.” But reality hit from time to time: “I particularly remember Fleurette Friedlander. One day, she was gone. She wore the Jewish star [a yellow badge, in the shape of the Star of David, that all Jews were forced to wear from June 1942, following Nazi orders]. She was a very clever girl who worked hard. At the time we didn’t know what was going on, we had no idea.” Seventy years later, Yvonne said she still wondered what had happened to her friend. I did some research and was able to tell her that the young Fleurette had gone into hiding in Paris and survived the Holocaust. She lived to an old age and passed away a dozen years ago.

Like Yvonne, other former pupils had memories of their Jewish classmates. Julie Mercouroff told us how one sudden disappearance continued to haunt her. She could not remember the young girl’s name but could still picture her face. “In 1942 she came to school one day wearing the Jewish star. That took me aback. She finished the school year but she did not return when term started again,” she remembered. “When I got a bit older and became aware of what was happening, I wondered if she had been taken away during a round-up. As an adult, I looked for her, but I never found her. Now, I’m upset with myself for having forgotten her.”

Some of the girls, scandalised by the treatment of their Jewish classmates, decided to take action. Sylvie Merle d’Aubigné, who was two years below Louise, remembered a show of support in class: “My mother was a resistance fighter at heart. When the Jews had to start wearing the [yellow] star, she encouraged me and my friends to make our own stars out of paper. We fastened them to our blouses at school. The head teacher lectured us, but our behaviour didn’t seem to cause too much of a fuss.”

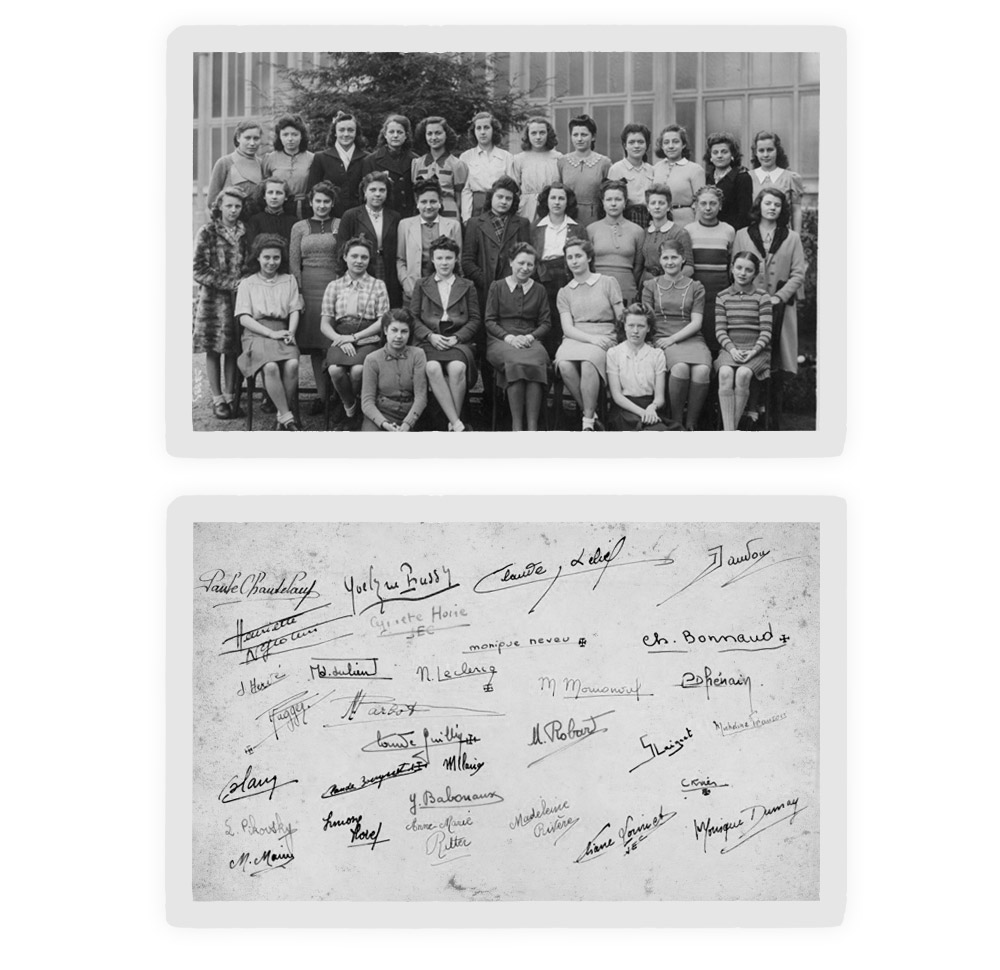

While Louise’s name did not ring any bells for the first women we tracked down, a photo of her class helped bring about a breakthrough in our research. Smiling shyly, Louise was sitting not far from her beloved Miss Malingrey when the photo was taken. More than a dozen classmates signed their names on the back of the photo. Several have since passed away but we were able to contact Liliane d’Espinose. The 89-year-old remembered Louise: “Oh yes, Louise Pikovsky! I remember her of course. One day she disappeared. Probably in a round-up. I never got any news of her. I asked what had happened, but was told no-one knew.”

We told Liliane about her former classmate’s terrible fate. “I’m sorry…” she said after a long silence, as if to apologise for not having known sooner. “I didn’t know her well, even though we were in the same class.” Her account corroborated the portrait of Louise we were starting to sketch: “She was always one of the best. That was not my case, far from it. I was very average! Louise was very serious, and also very kind. She was a very good pupil. You see, I haven’t forgotten her name. She made a mark on me.”

By a stroke of luck we found Madeleine Rivère, who sat next to Louise every day in class. “Louise was my classmate. It’s strange for me to talk about her. I’ve had a hard time sleeping since you contacted me,” she confided. Madeleine didn’t know exactly what happened to Louise, more than 70 years ago. “I guess she was taken in the Vel d’Hiv round-up in 1942, because she never came back to school. No-one saw her again and no-one had any news,” she said. In fact Louise was arrested 18 months later. When we told Madeleine her classmate had died at Auschwitz, she was not surprised: “I never knew for sure, but I had guessed. I think about it often, particularly when I watch films about the Holocaust.” Madeleine and Louise got on well at school. “We became good friends. We sent each other letters during the holidays. I kept them for a long time, until one day I had a clear-out…” she said, apologising for having thrown the letters away.

Like Liliane, Madeleine had not forgotten Louise’s academic prowess: “She was very discreet and very likeable. She came first in everything. She liked studying and worked hard.” The war did not dampen Louise’s appetite to learn but she never discussed the danger facing her and her family. “One day she came to school with the [yellow] star, but that was it. She never talked about her problems. We carried on like nothing was happening. I just remember that Miss Malingrey offered to let Louise stay with her because Jews were being closely watched and were often arrested. But Louise refused because she didn’t want to leave her family,” Madeleine explained. “Miss Malingrey was very Catholic,” she continued. “I think her religion encouraged her to want to look after Louise and I’m sure she was able to see Louise had outstanding abilities.”

After reading Louise’s letters, Madeleine was even more admiring: “These are really beautiful letters. She was so mature compared to me and others our age. It gives me goosebumps. We were friends, we were young and we had hoped to continue seeing each other. It still gets to me. I still think of her. To this day.”