Click to scroll

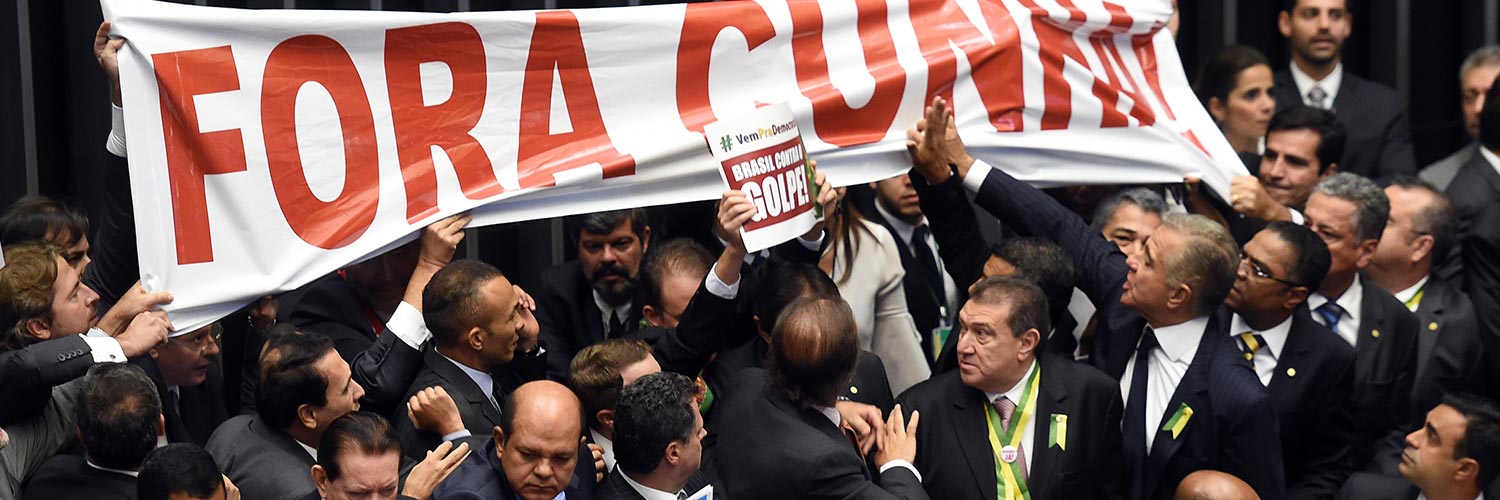

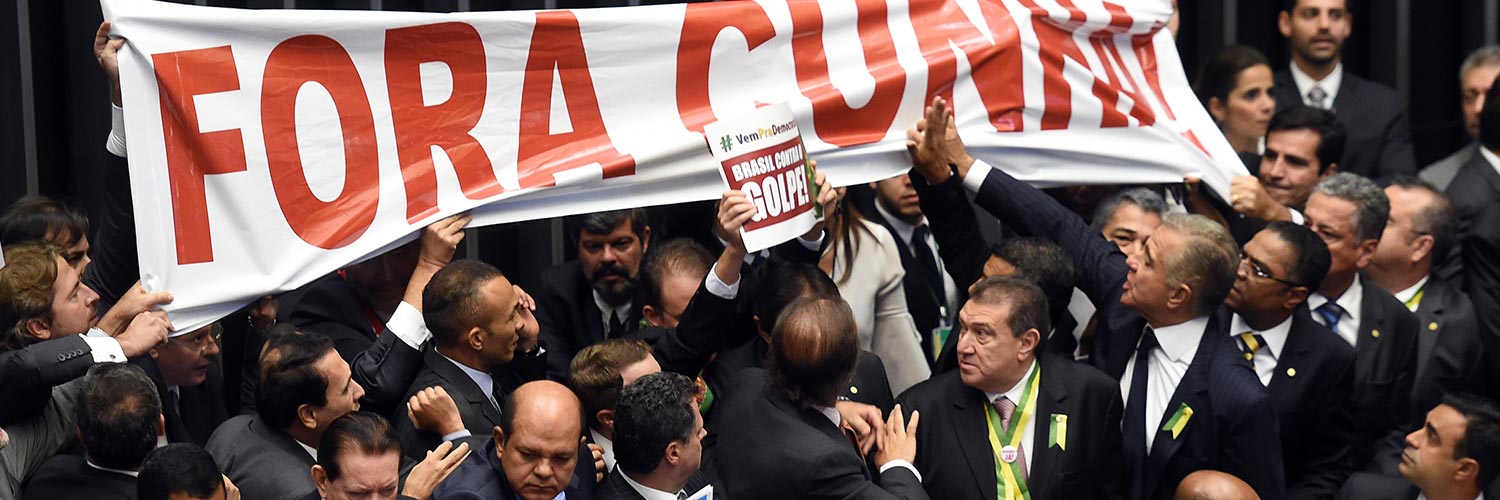

Opposition Brazilian lawmakers celebrate after launching impeachment procedures against then-president Dilma Rousseff on April 17, 2016 © AFP

In Brazil, Cuba and Colombia, 2016 will long be remembered as an historic year. The impeachment of the president of South America’s economic powerhouse, the death of “El Comandante” and the end of the region's longest-running armed conflict were among the highlights.

Cuba: Revolution bids farewell to historic leader

Former Cuban president Fidel Castro’s death, 58 years after he led triumphant revolutionary forces into Havana, marked the end of an era.

On March 21, Barack Obama landed in Cuba, making him the first serving US president to visit the island since Calvin Coolidge in 1928. Eight months later, on November 25, Castro passed away at the age of 90. A hero for some, a tyrant for others, Castro left a major mark on the 20th century. Will Obama’s visit and the death of “El Comandante” speed up political and economic change on the Communist-ruled island? The answer likely lies in the fate of the 1962 US embargo. Only US lawmakers can fully lift the embargo, but many in the Republicans-dominated Congress would prefer to extend it in 2017.

Colombia: Peace at last?

Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos and FARC leader “Timochenko” don symbolic white shirts for a historic handshake on September 26, 2016 © AFP

On September 26, the longest-running armed conflict in Latin America officially ended. In the presence of UN chief Ban Ki-moon, Cuban President Raul Castro, US State Secretary John Kerry, foreign dignitaries and more than 2,000 other guests, representatives of the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) signed a 297-page peace agreement in the city of Cartagena. After four years of intense negotiations – and after pulling them from the brink of failure – President Juan Manuel Santos and FARC leader Rodrigo Londono (better known by the nom de guerre “Timochenko”) smiled in relief.

The FARC has its origins in an insurrection by peasant farmers. The leftist group now wants to give up its arms and become a political party. © AFP

However, on October 4, as thousands of FARC fighters were preparing to surrender their weapons, Colombians voted against the peace accord in a national referendum. The “No” campaign claimed 50.21 percent of votes, only 60,000 ballots more (out of 13 million) than the “Yes” campaign, and the dream of peace appeared stillborn. Former president Alvaro Uribe, a constant critic of the peace talks, relished a political victory after convincing enough Colombians that the former rebels were getting off the hook after five decades of violence.

But on October 7, just days after the referendum defeat, Santos and the accord received a lifeline in the form of the Nobel Peace Prize. With the support of the international community, the Colombian government and the FARC reconvened in Havana for further negotiations. A week later, they managed to sign a new agreement after concessions by the guerilla army. Under the new text, the FARC maintains the right to enter politics as a normal party, but agrees to stiffer judicial oversight and to hand over its assets. To ratify the revised peace accord, Santos put it to a simple vote in Congress, were it is passed overwhelmingly on November 30.

Santos and Timochenko adopt a more sober tone for the signing of a revised Colombia peace deal on November 24, 2016 © AFP

The upcoming year nevertheless promises to be a challenging one for the peace process. Around 60 activists, often belonging to rural peasant organisations, were murdered in 2016, with many blaming paramilitary groups. The killings raise the spectre of a return of right-wing paramilitaries, who the FARC battled at the height of the Colombian conflict. Moreover, other smaller guerrilla groups remain active in the countryside.

Brazil: A political system implodes

Only a few days after then-president Dilma Rousseff’s ouster, Brazilian lawmakers also dismiss her political rival, parliamentary speaker Eduardo Cunha, on September 12, 2016 © AFP

In Brazil, 2016 will remain the year in which that the country’s political system descended into chaos, ushering former president Dilma Rousseff’s ouster.

Left-wing supporters in Brazil denounced Rousseff’s impeachment as a parliamentary coup d'etat © AFP

On April 17 after a hysterical parliamentary session that included insults, spitting and invocations for divine intervention, Brazilian lawmakers voted to launch impeachment procedures against Rousseff. Four months later, after several Senate votes, the country’s first woman president was definitively dismissed. Weakened by two years of economic recession and a vast investigation into corruption at state oil firm Petrobras that has tarnished the image of her Workers’ Party (PT), Rousseff left the Planalto Palace.

Michel Temer, 76, becomes Brazil’s president on August 31, 2016, ending 13 years of Workers' Party rule © AFP

A few hours later, Vice-President Michel Temer moved in and unveiled a very conservative, male-only cabinet as the country’s new president. But the political mess was far from over. In its first seven months, six of Temer’s ministers were forced to resign over links to various corruption cases.

Eduardo Cunha, the former House speaker who spearheaded the impeachment proceedings against Rousseff – and a member of Temer’s PMDB party – was arrested in October in connection to the Petrobras scandal.

Judges have also launched investigation proceedings against former president Lula Da Silva, in a further blow to the PT and the legacy of the once massively popular left-wing president.

Former president Luis Ignacio Lula Da Silva cries after being charged with corruption at the Workers' Party headquarters in Sao Paulo on March 4, 2016 © AFP

It is uncertain that Temer himself will finish his term as president. Suspected of having personally paid bribes, he could also face an impeachment procedure in 2017.

Venezuela: Economic crash and power struggle

The headquarters of Venezuela’s National Electoral Council in Caracas © AFP

In 2016, Venezuela’s conservative opposition embarked on a race against time to oust leftist President Nicolas Maduro by legal means. It set its hopes on a revocatory referendum, which, if organised before the end of the year, would have sparked new elections.

But those hopes were dashed in October, when judges called into question the validity of signatures that were collected as a requirement to organising the referendum. The move reignited dangerous tensions between the opposition and Maduro’s political camp, but they were diffused after mediation by the Vatican and the Union of South American Nations (Unasur) regional body.

But 2016 will be particularly remembered in Venezuela as a year of growing economic hardship.

A Venezuelan family receives a food parcel, rationed by a state-run shop © AFP

In February, the government – in desperate need of cash – was forced to massively reduce subsidies on fuel. A few months later, it forced schools and government offices to close for days in a bid to save energy. Most commodities were rationed, and supermarket shelves were emptied by a panic-stricken population. A defiant Maduro, the hand-picked successor of the late president Hugo Chavez, nevertheless refused to change economic strategy.

He called on the army to help cope with shortages of all kinds, ordering them to manage nationalised companies and fight “speculators acting on foreign orders”. And yet the lack of food and basic goods only appeared to worsen in the oil-rich nation as the year came to a close.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicts inflation will rise to 475 percent in 2016, while GDP will plummet by 10 percent. In 2017, inflation could reach 1,600 percent, the IMF has warned.

Argentina: A break with the Kirchner era

Residents of the Argentinian capital of Buenos Aires protest a rise in fuel prices, as much as 700 percent, on July 14, 2016 © AFP

Argentina’s economy also struggled in 2016, watching inflation soar by around 40 percent and GDP slump by 3.5 percent. The market-friendly economic reforms enacted by President Mauricio Macri, elected at the end of 2015, failed to reverse the trend.

Macri devaluated the Argentinian peso, eliminated taxes on agriculture exports, slashed around 200,000 public sector jobs, ended restrictions on imports and returned to international financial markets after cutting a deal with vulture funds in possession of Argentinian debt. Yet nothing appeared to work. Macri’s administration has kept its pledge to break with the economic and social policies shepherded by the late former president Nestor Kirchner and his successor, and widow, Cristina Fernandez. It’s no surprise that the unions are back in the streets, but the soup-kitchen lines also keep getting longer.

The year was also full of political and judiciary intrigue as scandals hit both Macri and the left-leaning opposition.

Former Argentinian public works secretary Jose Lopez is escorted to jail after his arrest on June 12, 2016 © AFP

In April, the Panama Papers leak revealed that Macri was among a handful of world leaders owning offshore accounts, thus considerably discrediting the president. In June, former public works secretary Jose Lopez was caught trying to stash close to $9 million in foreign currency, Rolex watches, jewellery and a semi-automatic rifle in a Catholic convent. Although he held a junior cabinet position, Lopez worked under both the Kirchner and Fernandez presidencies.

Lopez’s arrest was linked to suspected graft in government contracts in the southern province of Santa Clara. As the year drew to close, the intrigue only deepened when Fernandez herself was indicted in the corruption case. She has denied any wrongdoing.

Bolivia: First election setback for Morales

Bolivian President Evo Morales wears a necklace of coca leaves and is showered with flowers after his re-election victory in 2014 © AFP

Bolivian President Evo Morales is among the leaders who rose to power in South America’s so-called “pink tide” in the early 2000s. But his political star now also appears to be fading.

In a February 22 referendum, Bolivian voters rejected a constitutional amendment that would have allowed Morales to run for a third-consecutive presidential term. It was his first election setback in a decade.

The defeat for Bolivia’s first indigenous president came despite a positive economic record. During his time in office, growth has been cruising at a steady, and enviable, 6 percent. The nationalization of Bolivia’s gas sector and mining concessions to private corporations have funded public health and education programmes, as well as significant infrastructure projects.

Morales has nonetheless lost support, especially among young people and indigenous leaders, who say the government’s focus on exploiting natural resources flies in the face of his speeches about respecting nature and observing ancestral traditions.

In a troubling development, the former union leader-turned-president said in December he would seek re-election in 2019, despite the earlier referendum results.

Peru: The year ‘el gringo’ won

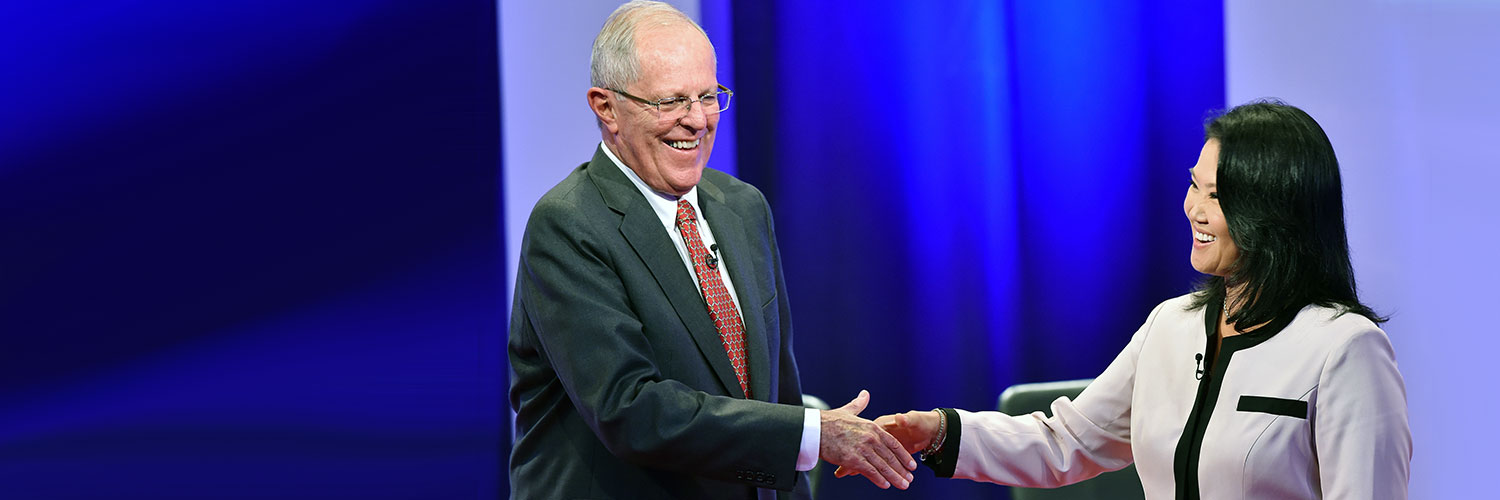

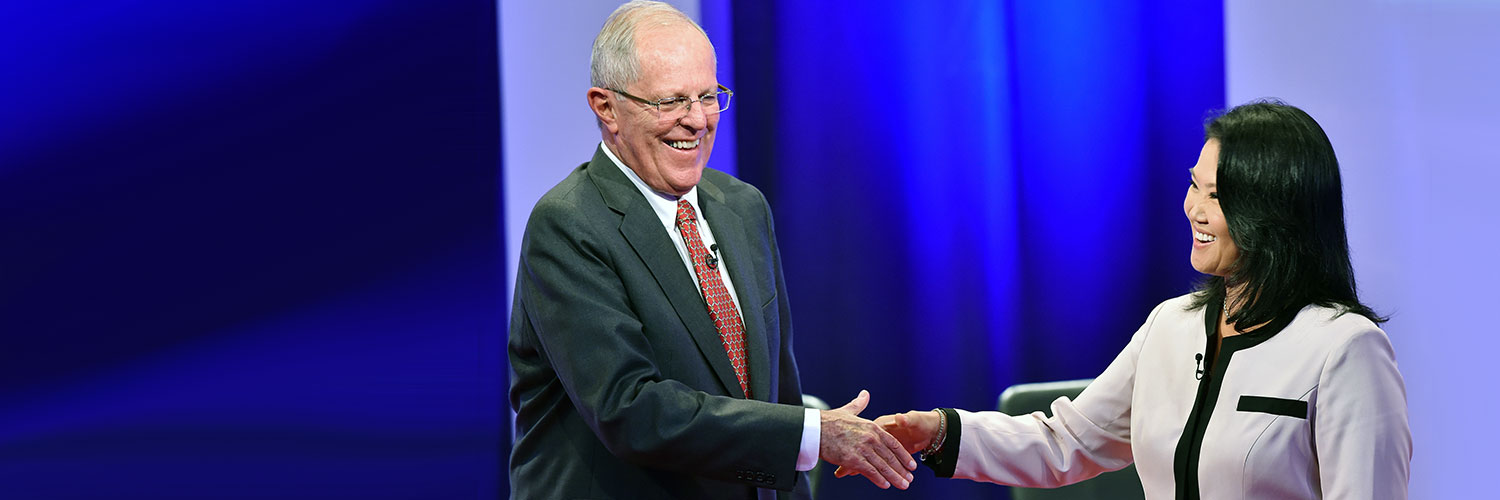

Peruvian presidential hopefuls Pedro Pablo Kuczynski and Keiko Fujimori shake hands following a televised debate on May 22, 2016 © AFP

In neighbouring Peru, former Wall Street economist Pedro Pablo Kuczynski won a tight presidential run-off election against Keiko Fujimori in June. Fujimori is the daughter of former Peruvian president Alberto Fujimori, who has been imprisoned since 2009 for corruption and crimes against humanity. Fujimori is one of the 100,000 descendants of poor Japanese immigrants who arrived in Peru in the first half of the 20th century. The children of these immigrants, who first toiled as agricultural workers and small traders, have since joined the urban middle and upper classes. Kuczynski is the son of a German Jewish doctor who fled Nazism, and is also a first cousin of the famed French film director Jean-Luc Godard. With a career that included studies in Britain and the US, and jobs at the World Bank and IMF, Kuczynski has lived outside Peru most of his life and even speaks Spanish with a slight accent, earning him the nickname “el gringo” among his countrymen. Kuczynski and Fujimori might diverge on style and politics, but their presidential campaigns this year helped illustrate Latin America’s rich cultural diversity.

CONCLUSION

If 1999 marked the beginning of Latin America’s left-wing turn or “pink tide” as Hugo Chavez’s rose to power, 2016 marked that tide’s retreat. The arrival of a “new right” in Argentina and Brazil, Venezuela’s economic collapse and, more symbolically, Fidel Castro’s death, herald a new era for a continent accustomed to political drama, fiery leaders, economic upheavals and ideological clashes. Yet, as the political scientist Andres Malamud points out, “in today’s world, it is a luxury to live in a negligible but democratic region of the world, without wars between countries. Perhaps soon it will be an exception.”