T

urkey, the transcontinental country that straddles Europe and Asia, has been witnessing tectonic shifts in recent years that accelerated after the July 15, 2016, coup attempt. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan promised a “cleansing” of state institutions that led to a tightening of his grip on power and sparked a major purge that upended the lives of hundreds of thousands of ordinary Turks. On the eve of the April 16 constitutional referendum, FRANCE 24 met with four victims of this purge.

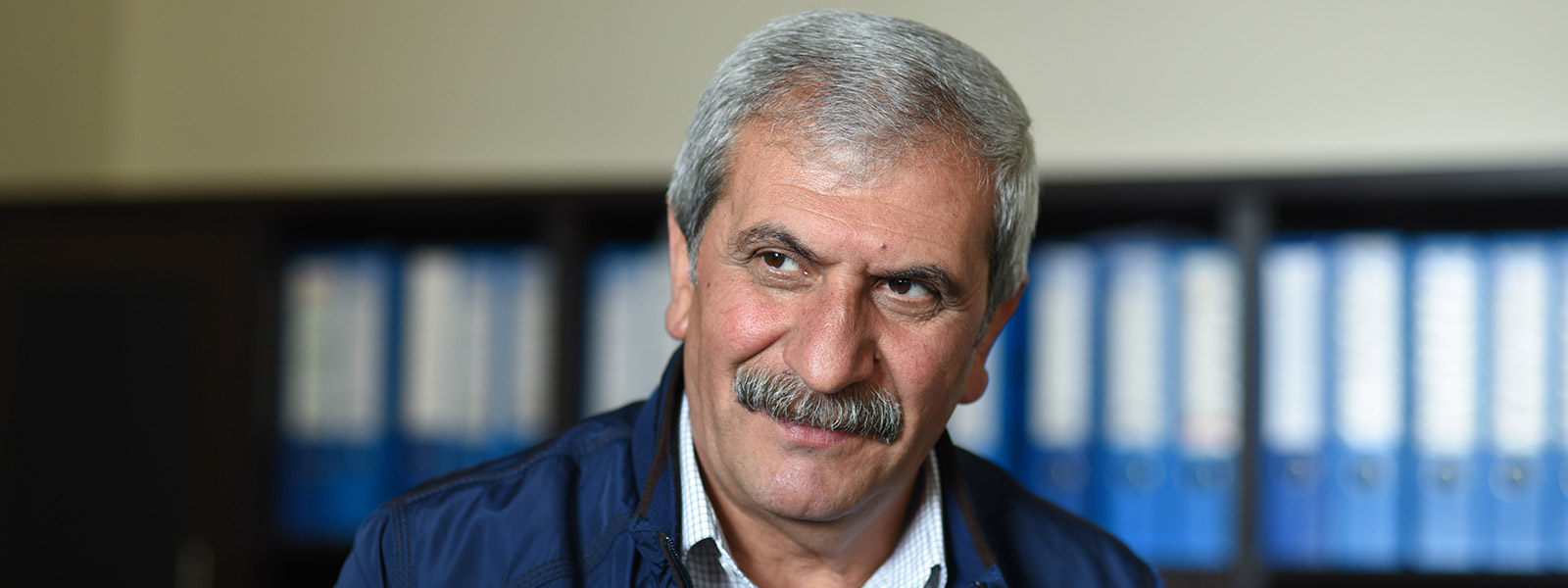

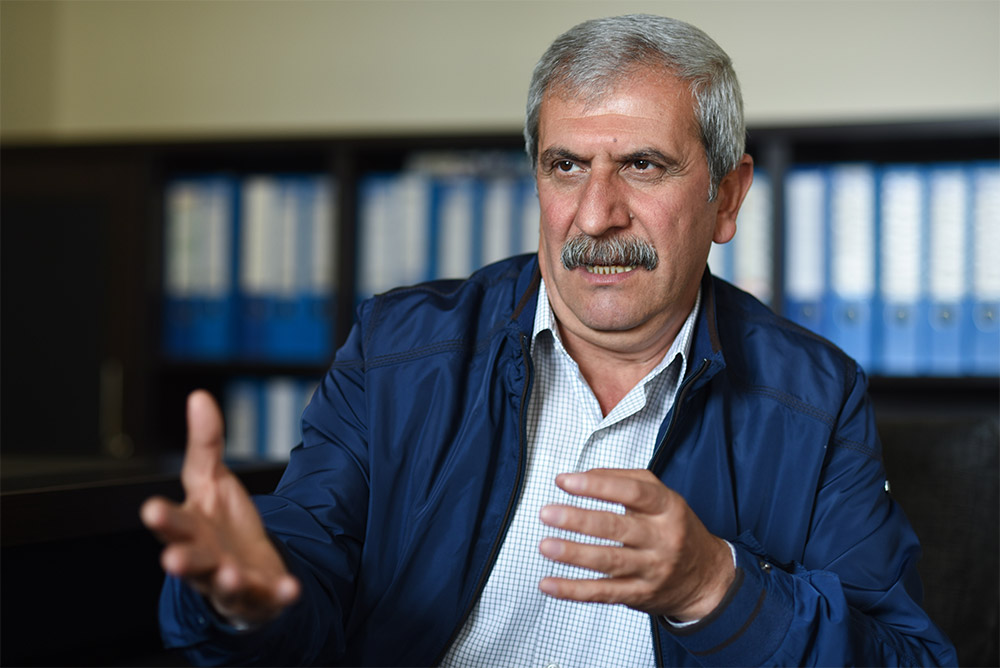

Exactly two weeks before Turkey’s controversial constitutional referendum, Mehmet Sah Teke switched on the TV in his Diyarbakir apartment to see what Recep Tayyip Erdogan was going on about. The Turkish president was a few metres – and yet a world away – from the Teke residence, addressing an “Evet” – or Yes – campaign rally in the Kurdish-dominated southeastern Turkish city.

Diyarbakir, though is an overwhelmingly “Hayir” – or No – zone.

Since the 2015 collapse of a ceasefire between the Turkish state and PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ Party) militants, police crackdowns, curfews and displacements triggered by heavy fighting have ensured that Erdogan is not well-loved in these parts.

But as a member of a pro-Kurdish opposition party being systematically suppressed by the Turkish strongman, Teke was interested in what Erdogan had to say in his city.

What the 56-year-old Kurdish father (of six surviving children) heard, however, had him cackling at the TV.

Erdogan, for reasons best known only to him, was discoursing on the political persecution he faced as an upcoming Islamist politician back in the 1990s. Recounting how he was jailed in 1999 when he was mayor of Istanbul for reading aloud a banned poem, Erdogan told the 5,000-odd people at the Diyarbakir rally, “I was fired as a mayor, I lost my post due to the political persecution.”

That cracked Teke up. “But that’s me,” he told the televised image of Erdogan. “I’m a mayor who has been suspended – by you!”

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan addresses a rally in Diyarbakir.

In August 2015, Teke was fired as mayor of Silvan, a city in Diyarbakir province, just over a year after he was elected with an overwhelming majority in the 2014 elections. His co-mayor was arrested and jailed for months, and Teke himself narrowly escaped arrest by going into hiding for 18 months.

Teke was one of 87 democratically elected mayors fired in the Kurdish southeast for alleged links with the PKK, a leftist group recognised as a terrorist organisation by Turkey, the US and the EU.

The Kurdish politician ran his successful 2014 Silvan mayoral race on the BDP (Peace and Democracy Party) ticket. The BDP was the regional sister party of the national, pro-Kurdish HDP (Peoples’ Democratic Party). It has since changed its name to the DBP (Democratic Regions Party).

Following the July 15, 2016, coup attempt, Erdogan promised to “cleanse” Turkey of a “virus” that has plagued its state institutions. That cleansing has been primarily directed at two organisations: the PKK and the Gulen movement – newly branded “FETO” (Fethullah Terrorist Movement) by the government after its founder, the Pennsylvania-based Turkish cleric, Fethullah Gulen.

But the crackdown on both organisations began long before the July coup attempt.

The HDP got caught in Erdogan’s political crosshairs after the June 2015 general election, when the pro-Kurdish party crossed the 10 percent vote threshold to make it into the Turkish National Assembly.

Alarmed by the party’s success, as well as the gains made by the Kurds in neighbouring Syria, Erdogan broke a ceasefire between the Turkish state and the PKK that had been holding for nearly three years.

With the collapse of the peace process, the situation in the volatile southeast got increasingly tense. A series of deadly Islamic State (IS) group bombings targeting Kurdish leftists sparked a PKK call to arms. The Turkish state’s response was brutal. Police and special forces units stormed into Kurdish neighbourhoods in cities such as Diyarbakir and Silvan. Heavy fighting killed more than 2,500 people, many more were displaced, and historic parts of these cities were levelled by the superior firepower of the state’s security services.

Diyarbakir’s historic Sur neighbourhood, which was destroyed in the fighting between the Turkish state and the PKK following the 2015 collapse of a peace process.

Erdogan’s political calculation to reignite the war with the PKK worked. Five months after his party failed to win a majority in the June 2015 general elections, the AKP won a 49.5 percent majority in the November 2015 revote. Turkey, Erdogan claimed, needed a strong leader to put down the terrorists.

'Erdogan is very stupid'

Now here he was, the most powerful man in all of Turkey, at a rally in Diyarbakir of all places, talking about his past political persecution.

Teke could only shake his head in resignation. “Erdogan is very stupid. When he is meeting other heads of state and leaders, he thinks he’s the smartest of them all. But in fact, he isn’t, and the other leaders are doing a better job administering their countries. Erdogan is stupid, but he’s too stupid to know that.”

At 56, and with a long history of political engagement behind him, Teke is one of a rare species in Turkey today: a man who is not afraid to stand up to the strongman in Ankara.

He also has, at his disposal, an infrastructure of resistance: his political party, his ideals, his friends, and above all, his family.

It was his family that saved him that fateful night in August 2015, when the police came to arrest him.

Teke was in his Silvan home, about 80 kilometres east of Diyarbakir, with his wife when the police arrived to arrest him at his Diyarbakir apartment at around 4am on August 19, 2015.

“My son, who was 12 at that time, was in the Diyarbakir apartment with my married daughter and her one-and-a-half-year-old baby. The counterterror police made my son and daughter lie on the ground and they put a rifle to my son’s head. My son, Tirej, got scared and started crying. The neighbours heard the noise and came out and started shouting at the police for putting a gun to a child’s head,” he recounts.

After the police searched and left the apartment, Teke’s daughter tried to call her parents to alert them. But the phone service was cut due to the security crackdown and so she eventually sent them a message on WhatsApp.

His wife, Nezahat Teke – an ample, cheerful woman who has weathered more than a fair share of personal and political trauma – held the family together during his hiding period.

An activist and member of the Peace Mothers – an NGO formed in the late 1990s of Kurdish mothers who have lost children to the insurgency – Nezahat is no stranger to police brutality. With their white headscarves and red roses, the Peace Mothers are a fixture on the Turkish civil rights scene, a particularly fearless lot who have confronted police brutality for decades.

In the couple’s Diyarbakir apartment, where the door still bears the impact of police break-ins, Nezahat bustles about, digging out her husband’s election campaign posters and producing WhatsApp photographs of her children on her mobile.

The door of the Teke’s Diyarbakir apartment still bears the marks of the August 2015 police raid.

On the wall behind the living room couch, a young girl in jeans and a shirt topped with a waistcoat beams from a photo frame. It’s Nesrin, the couple’s teenage daughter, who immolated herself in 2000 in protest at PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan’s arrest the previous year. Ocalan is currently in jail on Turkey’s Imrali prison island in the Marmara Sea.

Nesrin succumbed to her burn injuries on June 2, 2000, at a hospital in the Mediterranean coastal city of Adana and her death remains a difficult subject for her father. “She was affected by the lack of medical care Ocalan was receiving in prison,” he says. “One of her friends later told my wife that Nesrin wanted to go to the mountains,” Teke explains.

“Going to the mountains” is the Kurdish phrase for joining PKK fighters in their base in Iraq’s Qandil Mountains.

Teke looks at a photograph of his daughter, Nesrin, who immolated herself in protest at PKK leader Abdullah Ocalan’s arrest.

The PKK has had a magnetic pull on Kurdish youth since it was founded in the 1990s. With every crackdown by the Turkish state, the leftist organisation emerges stronger than before.

Shortly after Erdogan came to power, he won Kurdish support by opening up a peace process with the Kurdish separatist group.

But following the June 2015 election, Erdogan has calculated that the HDP alliance with civil rights and leftist groups was his most serious political threat.

His strategy has since concentrated on dividing the Kurds, turning public opinion against the HDP, and buying up Kurdish votes by doling out construction bids and land allocations in the destroyed parts of Kurdish cities that are being rebuilt.

“I cannot bear to go there and see what has happened.”

Today, Diyarbakir’s historic Sur district – a once bustling area of narrow streets crammed with homes jostling against UNESCO World Heritage structures – has been decimated. Access to the area, which is concealed behind tarps and concrete blocks, is virtually impossible, with police checkpoints dotting the area.

But during Erdogan’s visit to the city, a team of senior AKP officials were taken into the no-gone zone. They posed for pictures before the iconic 16th century four-legged minaret standing alone in empty, muddy ground that was once home to numerous historic houses and shops. Behind the pillar, the outer walls of the historic Surp Giragos Armenian Church can be seen, with holes gaping in the brick façade.

In Diyarbakir’s historic Sur district, an iconic 16th century minaret stands desolate in empty ground. Behind the structure, the walls of the Surp Giragos Armenian Church can be seen.

Teke, who grew up in the district, shakes his head sadly when asked about Sur. “I cannot bear to go there and see what has happened,” he confessed.

Blame for the destruction, however, can be pinned on both the Turkish authorities and the Kurdish rebels who dug into the historic district during the 2015 fighting.

But Teke is not one to condemn Kurdish fighters. He does however deny his party’s links with the PKK. “There is no link between the PKK and HDP,” the former Silvan mayor insisted. “The ones who vote for the HDP may also sympathise with the PKK. But we don’t agree with the Turkish state that the PKK is a terrorist group. If you’re a terrorist organisation, you wouldn’t have the support of millions as the PKK does.”

The Kurdish cause has taken a toll on Teke’s family life. In February, just weeks after he emerged from hiding, police raided Teke’s Diyarbakir apartment again, this time looking for one of his sons, who was not at home. His son, Mazlum, has since gone into hiding.

"I do not know where he is at the moment," says Teke evasively. "But I was the one who warned him the day before the raid not to stay home on February 15. It’s the anniversary of Ocalan’s capture and I know from experience that the police conduct raids on this day.”

After a lifetime of political engagement, Teke can impart valuable survival lessons to his children. But he can’t protect them from the ravages of a life in the resistance.

A photograph of Tirej, Teke’s youngest son.

Two of Teke’s older sons have spent time in prison and he knows that his youngest, Tirej, has sometimes skipped school to attend demonstrations. His wife, Nezahat, has also been in the news, protesting against police excesses during Peace Mothers demonstrations.

Has it all been worth it?

“We, as a family, have paid a very high price for our ideals, I lost one of my daughters…” he breaks off, stares stoically ahead, before continuing, “But I don’t have any regrets.”

For Teke, the political struggle goes on. Taking advantage of the fact that he is no longer wanted by the police, he is now invested in the “No” campaign ahead of the April 16 constitutional referendum.

Teke has no interest in seeing Erdogan strengthen his powers, but he doesn’t have much hope that the campaign to curb his presidential powers will succeed. His party, the HDP, is part of the “No” campaign, but its campaigning position has been notably weakened by the arrests of several senior party officials, including the charismatic HDP leader, Selahattin Demirtas.

But Teke is not pessimistic about the HDP’s future. “The party is still in good shape. We Kurds have faced repression in the past, this is not the first time. The government tries to weaken our party, but we still have popular support.”

A history of resistance will no doubt see the Kurds through this latest form of oppression by the Turkish state. What amuses Teke, though, is to see how pessimistic other Turkish opposition and civil society groups have grown following the post-coup crackdowns.

"We have tried several times to denounce the threats [against human rights] that this government constitutes but the people in western Turkey thought we were exaggerating. Now they are awake and they understand,” said Teke. "Maybe in the future they will be more open to supporting us in difficult times.”