Greece is in the eye of the two storms tearing Europe apart, first pummelled by austerity and now quarantined to keep migrants at bay. Its people have opened their hearts and homes to those in need, even as wealthier countries close their borders. But with the twin crises festering, this impoverished nation of 11 million is being pushed to breaking point.

The collapse in public services triggered by Greece’s drastic austerity cure has coincided with a surge in the number of community initiatives and NGOs. Greek people have had to fend for themselves, without support from a state they have long regarded with suspicion. The great disillusion that followed the Syriza government's failure to end austerity only heightened the sense that politicians could not be trusted to solve Greece’s problems and look after those in need.

Across the country, ordinary citizens have pulled together to set up food banks and shelters. Many now cater to both locals and migrants. In Idomeni, the village where thousands of desperate migrants have been stuck in squalid conditions since Macedonia closed its border, many locals have opened their doors to families with small children. There have been numerous reports of villagers sleeping on couches while hosting up to two families in their homes. There have also been protests, including by farmers whose fields were taken over by the sprawling camp. A handful have complained of migrants squatting in abandoned buildings.

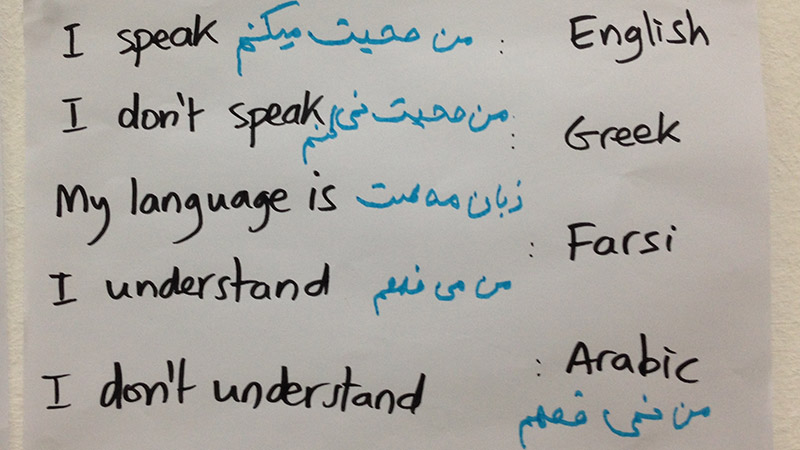

In the Athens borough of Exarchia, known for its leftist politics, we visit a former secondary school where 292 migrants live in deserted classrooms. They include 20 pregnant women and 103 children, one of which is just two days old. Arabic classes are dispensed by teachers who came with the migrant flow. We are told that Greek volunteers will soon be teaching the local language. Among them is Maria Malafeka, a retired teacher who used to work for the nearby French Institute.

Malafeka has brought biscuits she baked at home. She says every day someone gives her food, clothes or toys to take to the school's new dwellers. “I spoke to the butcher, he gave me three chickens. Then I spoke to the fishmonger and I got four kilos of fish!” she exults in fluent French, before adding, in a dig at France and its president: “[François] Hollande is good at bombing countries. But then he won't take any refugees!”

Hollande is good at bombing countries. But then he won't take any refugees!

In the school's playground we find Halina Karetas, a Briton who moved to Greece 30 years ago. She is teaching boys and girls how to knit. Karetas is not surprised by the warm welcome extended to refugees. She says Greeks are always hospitable, even more so since the crisis. “Because of their own hardships, they have perhaps more empathy for the suffering of others,” she explains. And unlike many people in the rest of Europe, the Briton adds, “Greeks are not afraid of terrorism; they don't make a link with the refugees.”

The school in Exarchia is run by a group of local volunteers whose leader goes by the name of Kastro, “like Fidel”. Sitting down for an interview with the bearded, under-slept and over-caffeinated Syrian immigrant is no mean feat. His office is bursting with heaps of donated food and clothes, while migrants, volunteers and other passers-by wrestle for his attention. Kastro jumps from one conversation to another, shifting seamlessly between Greek, Arabic and English. Every few minutes a newcomer walks in to bring biscuits, fresh milk, or the keys to an apartment where migrants can take a shower or do their laundry.

Kastro acts as a crucial link between migrants and Athenians willing to help. The walls of his office are plastered with the names, addresses and phone numbers of people who have offered to put up migrants or let them wash at their homes. He tells us he has been able to find accommodation for some 200 Syrian and Afghan families. “Golden Dawn told us, 'Take them to your homes',” he scoffs, referring to Greece's neo-Nazi party. “So we did just that!”

An openly racist and xenophobic outfit, Golden Dawn has emerged as Greece's third-largest party in the wake of the economic crisis. It has so far failed to pick up more than 7 percent of votes cast in national elections and capitalise on the refugee crisis. But many Greeks fear the build-up of migrants in places like Piraeus and Idomeni will give the far-right party – and racism more generally – a new lift.

“Once Greek people realise that the 50,000 migrants are here to stay, reactions will be very different,” says Aris Messinis, AFP's chief photographer in Greece, whom we meet for a coffee in central Athens, a stone's throw away from Syntagma Square, the site of many huge rallies – some of them violent – in recent years. “Greeks are hospitable and compassionate so long as we don't see [the migrants],” he adds. “But once we see them, we will become like other Europeans.”

For the past six years, Messinis has captured the tragedy of Greece's twin crises with pictures of tearful pensioners outside shuttered banks and shell-shocked refugees landing on beaches. He offers a scathing assessment of Europe's handling of the situation and the Greek government's own failings. “When there is a problem, you see the real face of people,” he says. “Now we have seen the real face of Europe.”

Once we see the migrants, we will become like other Europeans

According to Messinis, the relentless squabbling and lack of solidarity displayed by EU countries in response to the flow of refugees is evidence that the union has lost sight of its core values. “The humanitarian crisis is in Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq – not in Europe,” he notes. “Here we have an ideological crisis. Hospitality, tolerance and multiculturalism have vanished.”

The veteran photojournalist describes the EU’s deal with Turkey as “the joke of the month”. He claims Europe is being turned into a detention centre because “Germany has already taken the middle class, educated Syrians it needed to sustain its economy,” leaving the poorest behind to rot. He pours scorn on the Greek government's supposedly humane policies, predicting that the new migrant camps it is hurriedly building “will be just as bad as those it promised to shut”.

His sardonic smile turns into a scowl when we touch on the subject of NGOs. Messinis says many of the foreign organisations that set up camp on Greek islands are little more than PR machines that have done more damage than good. “Many NGOs simply satisfy their own ego,” he erupts. “They compete to 'rescue' the boats landing on beaches. They hug exhausted and traumatised refugees in bikinis. They snatch babies from their mothers' arms to take pictures and post them on Facebook so as to claim credit for their rescue. This way they get more donations. It is all about money and self-promotion.”

The presence of thousands of volunteers from around the world has helped offset the decline in tourists visiting Greece as a result of the migrant crisis. At the Anita-Argo Hotel in Piraeus, a short walk away from the port, all 45 rooms are taken by volunteer workers – an unusual tally for what is still low season. Jenny Klitsidi, the hotel manager, estimates she would have 30 percent less business were it not for the migrant crisis. She says some of the wealthier families from Syria also rent rooms.

Like many other hotels in the area, the Anita-Argo regularly donates used blankets and towels at the port. Occasionally, it lets migrant families in for a shower. But Klitsidi is worried about the tourist season. She cannot understand why the government does not evacuate the harbour, noting that tourism is “Greece’s last industry”. “We have no problem with refugees, but they cannot stay at the port,” she explains. “Would you feel good holidaying with so many refugees next to your boat?”

Klitsidi says she offers a discount when refugee families stay at her hotel. Others have been accused of inflating prices. There have been reports of migrants being charged an excess fee of up to €40 euros to buy combined ferry and bus tickets from Lesbos and other Greek islands to Idomeni on the Macedonian border. At the Aeolian Sun travel agency in Mytilene, the main town on Lesbos, we are told that it is no longer possible to buy tickets all the way to Idomeni because the bus service has been stopped. Migrants are also banned from boarding ferries bound for the Greek mainland. A member of staff confirms that smugglers and profiteers used to charge higher prices for migrants, but that they have been chased away by police.

“We made good business for a while, selling more tickets than usual in low season. But now it's over and it's too early to know what impact this will have on the summer,” she says, before adding, despondently: “This is a war zone. How can we expect tourists to come?”

Would you feel good holidaying with so many refugees next to your boat?

We arrive in Lesbos just as the island prepares for the start of deportations back to Turkey. The remote outpost that has borne the brunt of the migrant flows will also be the first to witness their expulsion. A sense of denouement hangs over the island, where hundreds of unmarked graves hold the remains of those who perished during the crossing. Now that newcomers are locked up in a detention centre as part of the deal with Turkey, most NGO workers are packing up. Many have already left for the mainland, shifting their operations to Piraeus, Athens or Idomeni.

This is bad news for local businesses, who are in danger of losing both tourists and volunteer workers. But for the time being, a new type of visitor is offering some respite. Greek authorities and the EU are urgently flying in hundreds of immigration officials, legal advisors, translators and security agents in an increasingly frantic race to process asylum applications and apply a veneer of legality on the controversial expulsions to Turkey. They include a contingent of riot police sent by France. And with journalists also out in force to cover the start of deportations, hotels around Mytilene are once again fully booked.