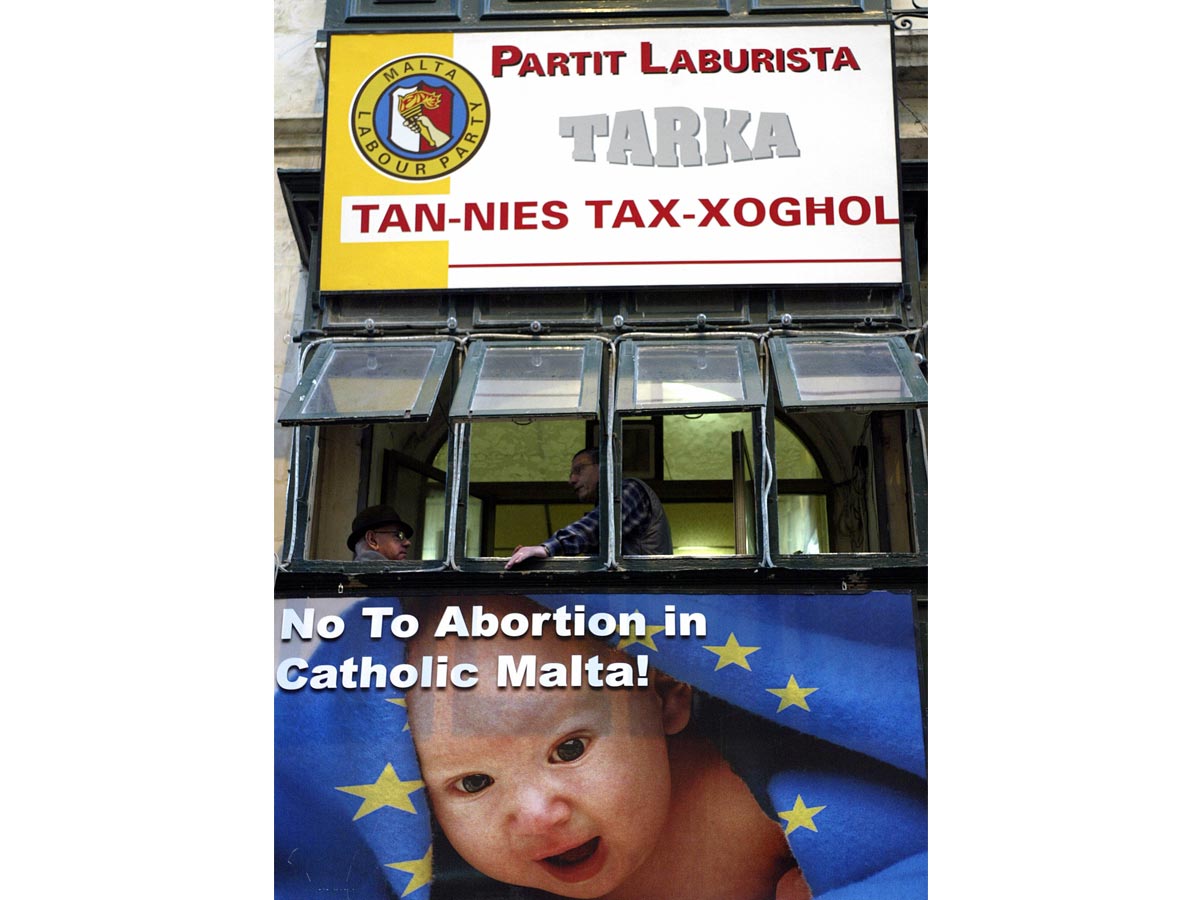

Last May, when Ireland voted overwhelmingly to overturn a ban on abortion, the historic vote was cautiously observed in faraway Malta. A small revolution had just shaken one Catholic island in northwestern Europe, but the southern islanders were largely unmoved. The smallest state of the European Union is now the only one to ban abortion – and its stance is unlikely to change any time soon.

For much of Maltese society, there’s no such thing as an abortion debate. In conversations between colleagues, friends or family, the word itself is taboo. Finding people who are willing to discuss the matter requires discretion and a focus on social media via women’s discussion forums. After many fruitless searches, the profile of a young woman with a broad smile and ebony hair finally pops up.

“We can talk, as long as it remains anonymous,” says Victoria (not her real name), 26. Meeting in public, however, is unthinkable. “It’s too risky, my boyfriend doesn’t know about this,” she explains. “It’s a small place here, you have no idea how quickly people find out.”

The worst experience of my life"

— Victoria

Victoria became pregnant in January 2016, despite being on the pill. She recounts the ensuing ordeal in a series of private messages. “I did it all myself,” she starts off. “I didn’t mention it to my boyfriend at the time because I knew I couldn’t rely on him. I simply cut all ties.” Nor did she tell her “very Catholic” parents, certain that they wouldn’t have understood her choice. “It was the worst experience of my life,” she adds. “I couldn’t go to hospital or else I would have been arrested.”

On the Mediterranean archipelago, where Catholicism is the official religion, women who have an abortion can be jailed for up to three years. Health practitioners who help them incur a four-year jail term and a lifetime ban from the profession. No exception is tolerated, not even in cases of rape, incest, fetal malformation or life-threatening risk to the woman’s health.

In 2014, a 30-year-old woman who took an abortion pill was given a two-year suspended jail term, according to the Women's Rights Foundation (WRF), a Maltese feminist group. The person who supplied the pill got an 18-month suspended sentence.

To terminate an unwanted pregnancy Maltese women have just two options: secretly taking an abortion pill or leaving the country. Each year between 300 and 400 women choose to have an abortion abroad, often in Britain or in nearby Sicily. That was not an option for Victoria, who couldn’t leave her work. So she turned to Women on Web, an Amsterdam-based NGO founded by Dutch doctor and activist Rebecca Gomperts.

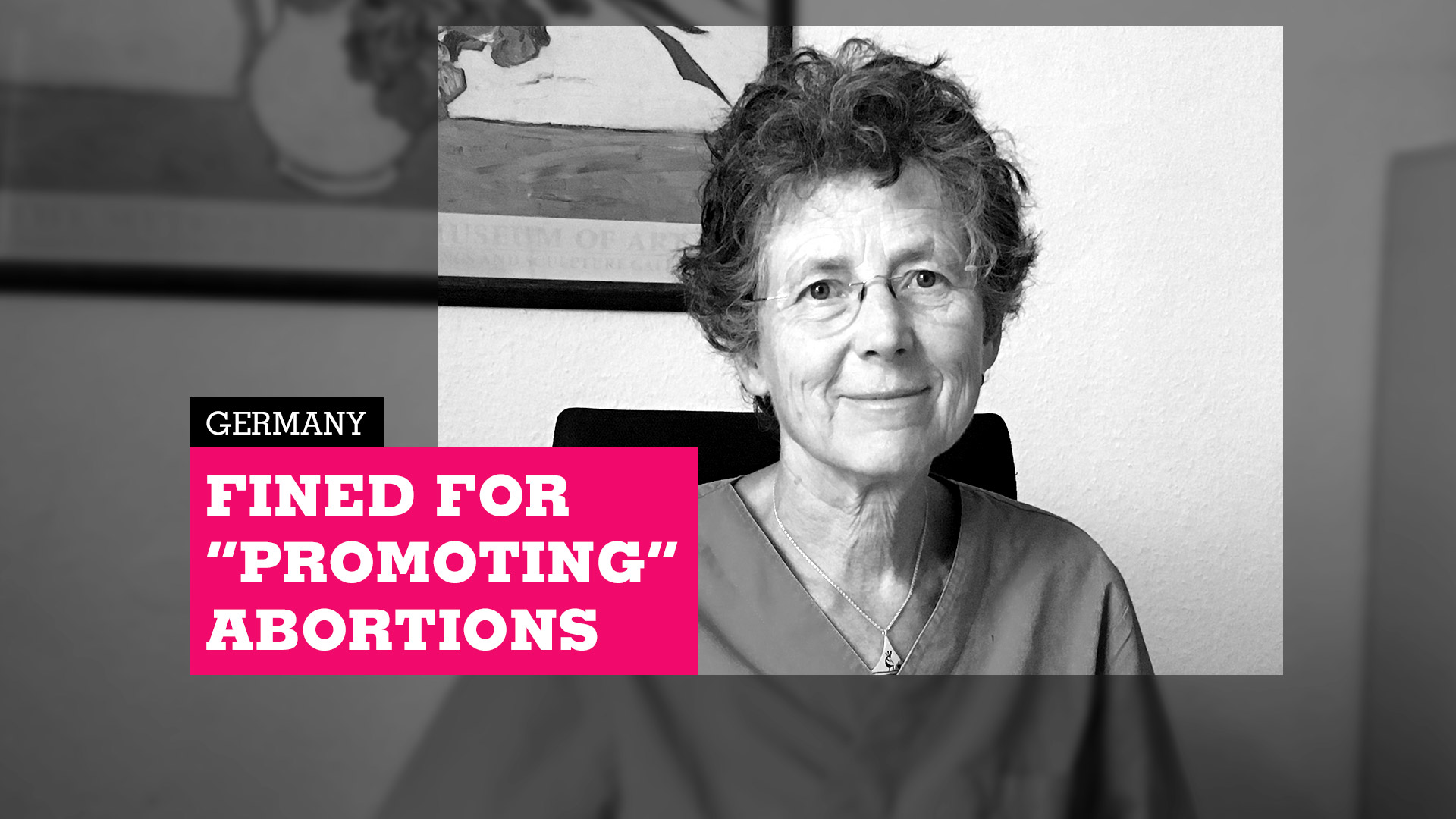

Gomperts has dedicated her life and work to helping women safely terminate pregnancies in places where the practice is illegal. In 1999 she set up Women on Waves, a charity that provides abortions onboard medical clinics sailing in international waters. Women on Web has a similar purpose: mailing abortion pills to women who want to end their pregnancy at home.

Easy and quick to order"

— Victoria

After filling out a form online to establish the date of conception and avert complications, Victoria was referred to a doctor who prescribed two pills, mifepristone -- better known as RU-486 -- and misoprostol, which cause a miscarriage in the first three months of a pregnancy. The package was delivered to her home address in return for an 80-euro donation. “It was relatively easy and quick to order,” she says, though the parcel had been opened along the way and one pill was missing. “I decided to take the remaining one anyway, I had no other choice,” she adds.

While the World Health Organisation (WHO) considers medical abortions to be safe, Victoria experienced complications. “The pain was unbearable and really traumatising,” she recalls. Women on Web, whose website warns about pain, cramps and bleeding after taking the pills, advised her to see a gynecologist. Victoria was diagnosed with multiple cysts. She didn’t say which pills she had taken, fearing it would land her in trouble. Summing up the tight-lipped tête-à-tête with the doctor, Victoria adds: “She didn’t ask a single question, and I didn’t say anything either.”

The traumatic experience of terminating a pregnancy can have major psychological repercussions. Victoria went through a bout of depression and suffered from anxiety attacks. Two years on, she feels she has turned the page, though she still sounds apologetic when discussing her choice. “Don’t get me wrong, I love children; but I really couldn’t have any at the time,” she explains.

Most women who choose to have an abortion feel guilty about it, says Alice Taylor, a prominent feminist author from Malta. “Our society has no tolerance for those who don’t want to become mothers or who choose to terminate a pregnancy,” she protests. “In this archipelago, sexuality is taboo and people are not free to speak their mind. It’s no less than a form of self-censorship.”

I was one of the first women to write for a Maltese paper in support of the legalisation of abortion"

— Alice Taylor

This culture of silence is a result of the Catholic Church’s pervasive influence, says Maltese student Liza Caruana-Finkel, who is studying for a Master’s degree in Gender and Women’s studies at the University of Lancaster, in the UK, and has written a dissertation on abortion in her home country. “It all starts at a very young age, with religious education classes in state schools,” she says. “Teachers have recently told me they are required to say that abortion is a bad thing, and contraception too.”

I received death threats"

— Alice Taylor

Determined to break the silence on abortion, Alice Taylor has written several articles on the highly sensitive topic in The Malta Independent, one of the country’s few independent newspapers. Her articles met with vitriolic responses. When she suggested that abortion should be legalised in cases of rape or if it posed a risk for the woman’s health, she received death threats online. “These people even targeted my mother, who’s 74 years old!” she says. “They told her they wished she had been raped so she would have aborted me.”

Taylor, whose Facebook page was hacked, says a group of “eight to ten fake profiles” is behind a campaign of online harassment targeting her. “They regularly spread false information about me, saying things like I have a criminal record – I don’t –, that I’m a murderer, that I’m a fake person being paid by the women’s rights agenda to push the issue forward,” she says. Exasperated, Taylor pressed charges and then left the country last September. “Why should I just sit there enduring their threats and being scared to even take the bus?” she explains.

People have started to publicly say they are pro-choice"

— Alice Taylor

Still, the author is proud to have helped shake things up. “Since I started writing about it, people have started to publicly say they are pro-choice,” she says, whereas “up to a year or 18 months ago, nobody would dare to”. Some Maltese women now even discuss the matter on social media, notably on the Women for Women Facebook group, which counted 27,000 members in July. But even there, “the faintest pro-abortion remark is immediately followed by death threats,” Taylor laments.

Francesca Conti, who created the Facebook group and is herself pro-abortion, explains that the forum is open to all – including pro-life activists determined to preserve their monopoly on the subject. “They tell us to keep our legs shut, to stop being sluts,” she says, appalled at seeing “these women formatted by a patriarchal society”. Sometimes she steps in to block comments that are too vicious, or profiles she deems too extremist.

We knew we had to rapidly press ahead with reproductive rights"

— Lara Dimitrijevic

There are other signs that things may be slowly changing. Earlier this year, Lara Dimitrijevic, who heads the WRF, stirred up a hornet’s nest by presenting the Maltese government with a policy paper on women’s “sexual and reproductive health and rights”. The paper notably calls for safe and legal access to abortion in four “exceptional” circumstances: to save a woman’s life, in cases of rape or incest, and in the event of fatal fetal impairment.

The WRF is hopeful the proposal can finally move the abortion debate forward in Malta. Its latest push comes on the heels of a first victory in 2016, when, after a fierce debate, it secured a law authorising sales of the morning-after pill – though many pharmacies still refuse to comply.

“We knew we had to rapidly press ahead with reproductive rights,” says Dimitrijevic, who has also received death threats since releasing the paper in March.

Caruana-Finkel, the Lancaster student, sees the WRF’s proposal as a real step forward. “It fits into a global approach that includes better sex education at school and improved access to contraception,” she explains, adding: “It also has the advantage of not mentioning abortion in the title, in order to avoid offending the public and the political establishment.”

Touching on abortion would be political suicide"

— Alice Taylor

In recent years, civil liberties in Malta have been dramatically expanded, starting with a watershed referendum that paved the way for the legalisation of divorce in 2011. More legislation soon followed, including a groundbreaking law on gender identity passed in 2015 and one legalising same-sex marriage two years later. Today, Malta is seen as a model for Europe when it comes to LGBT rights.

Abortion, however, the Church’s last great interdict, is a tougher mountain to climb.

“The Socialist government agrees to move forward on certain liberal issues, such as divorce and civil unions, because voters are moving in that direction,” says Taylor. “But touching on abortion would be disastrous, political suicide,” she adds, before concluding: “Until society moves forward on this subject, politicians will stay put.”