Click to navigate

The battle against corruption

at the World Bank

“Corruptionˮ and “developmentˮ: the association of these two words has cast a long shadow over relationships between nations of the North and South. There is a certain taboo and the development community is reluctant to talk openly about fraud, collusion, or corruption in projects that cost millions. This is partly to avoid disrupting the flow of donations – mostly from Western governments – but also stems from a fear of delaying the development agenda. In Washington the World Bank, the institutional leader in development aid, has long been criticised for showing an inclination to pay out without bothering too much about accountability. It wasn’t until 1996 that the Bank’s then president, James Wolfensohn, gave his revolutionary speech on what he called the “cancer of corruption” – a phrase that was not, until then, a part of the institution’s vocabulary. The Bank’s anti-fraud and corruption framework, the Integrity Vice Presidency or INT, now includes staff with law enforcement backgrounds, lawyers, prosecutors and forensic accountants – a new generation with a new ambition: eliminating transnational fraud and corruption.

World Bank headquarters in Washington, DC © Laurence Soustras

In 2015 the investigators reviewed 61 projects and 93 contracts totaling $523 million. In the event of any wrongdoing, the Bank has the power to impose temporary or definitive bans on participating in the institution’s projects. However the practice of bribing senior government officials has become ever more sophisticated. Gifts in the form of deluxe trips or fake study tours mask compensation paid for awarding public contracts. More and more illicit operations – such as ingeniously doctored kickbacks and the creation of shell companies – are carried out through intermediaries.

“It seems to be a growing trend for multinational companies to use local agents, both because they are more effective at negotiating ‘arrangements’ around contracts, and also as they are harder to investigate and, ultimately, sanction,” says Dave Fielder, World Bank head of corruption investigations.

A handful of multinationals, such as Siemens, SNC-Lavalin and Alstom, have been temporarily banned from participating in World Bank projects. The negotiated settlement process has also sometimes allowed for the recovery of funds and helped instill a culture of good governance in the companies involved.

On the ground, where development projects are implemented, fraud and corruption never sleep. But beneficiary communities and whistle-blowers are determined not to get caught napping.

Armenia: the post-corruption era ?

The rooftops of Yerevan © Laurence Soustras

Seen from the surrounding hills, the Armenian capital appears nestled in a misty valley. For years Yerevan's 1.2 million inhabitants lived with potentially lethal water due to the decrepit piping dating back to the Soviet era – despite a $30 million loan from the World Bank to help improve the water supply. At that time few would have imagined that the programme would be the catalyst for a pitched battle between the World Bank and a highly determined whistle-blower. The whole saga would leave a bitter taste. “What happened? Corruption happened,” one resident commented, “and today, it is still here, growing at a large scale.”

When Armenia emerged from the Soviet era the newly independent nation had to deal with the appalling state of its water supply network. Installations were ageing and dilapidated. Drinking water pipes under the city ran dangerously close to waste water pipes above them. Just 15 years ago Yerevanians only had two to four hours of drinking water a day – water that was all too often polluted by leaks from damaged pipes.

Soviet-era buildings in Yerevan © Laurence Soustras

At the beginning of the year 2000, the World Bank granted Armenia its first loan to renovate Yerevan’s drinking water supply network. According to accounts given by those actually involved in the project – among them local engineers – initial studies had not taken into account the full extent of the damage to the network. The project players were facing an unexpected crisis situation, and made do with the resources they had. If the Armenian parliament had not decided to set up a commission to audit projects that had received development aid, the whole affair would probably have been written off as a project dogged by dubious calls for tender. The responsibility for the investigation was put in the hands of Bruce Tasker, a British engineer living in Armenia.

Bruce Tasker, whistleblower in Armenia

In 2005 the commission started examining the World Bank-funded project. Looking back, Tasker says: “It very soon became noticeable that there were inadequacies and irregularities throughout the project.” The investigation found evidence of a conflict of interest between the state water board and the company managing the project. Worn-out equipment had simply been repainted to look new. Despite fierce opposition from local representatives of the World Bank at the time, the commission published its findings. Armine Avetyan, then a journalist with the online media group “168”, was present when the conclusions were presented. “The atmosphere in the room was totally explosive. There were journalists, diplomats, NGOs, members of the development community. And suddenly the president produced these pictures of the Soviet-era pipes that had been repainted blue so that they would look new. He was very angry and shouting. We were all shocked. It was the first loan contract in the new Armenia. Everyone was expecting a full-scale investigation and some arrests.”

“Old pipes from the Soviet era repainted to look new”

Armine Avetyan

Pipes in a residential building in the Nubarashen district of Yerevan. © Laurence Soustras

Nothing of the sort happened. Shortly after, government authorities declared the subject closed and sat tight-lipped. Tasker soldiered on. He discovered evidence of creative accountancy in the state water board’s bookkeeping intended to under-value the company’s assets. Years later, under pressure from the American Government Accountability Project (GAP), the World Bank launched its own investigation based on Tasker’s allegations. The Bank found no proof of tampering with equipment or of misappropriation of funds in the programme’s official documents. Nothing was said about the modification of objectives: The project’s initial brief was to install 20,000 water meters and renovate the network. On completion, the project leaders were proud to announce that there were now 277,000 water meters. Although the network was far from renovated, the World Bank declared the project “satisfactory.”

Mysterious cases of water contamination in Erevan.

More than a decade later, the water supply is still a controversial topic in Yerevan. The work had seriously modified water pressure and numerous pipes had ruptured, leaving drinking water contaminated. In 2003 a neighbourhood that is home to a quarter of a million people was affected: 257 people, including 163 children, were hospitalised with intestinal infections. The same thing happened in 2007. World Bank staff based in the capital at the time of the project were transferred elsewhere in Central Asia. The financial institution granted the project a second loan of $20 million and a French company, Veolia, took over running part of the city’s network – with debatable results.

Inhabitants living close to old and damaged piping said the attempted repair work seemed makeshift and the general feeling was that no one wanted to pay for the renovation.

“Although the situation has improved and the number of accidents has reduced, there are still communities where water pollution can lead to diseases and, in acute cases, people need to be hospitalised,” claims Knarik Hovhannesyan, a water specialist and an expert appointed by the parliamentary assembly.

That is just what happened two years ago in Nubarashen, a district to the south of the Yerevan urban community. The town’s main street is lined with buildings from the Soviet era – water pipes stick out from the ground. “Children fell sick first with diarrhea and dizziness. It was going on and on, one after another. Doctors were taking turns and staying in the buildings to treat all the sick people,” one inhabitant said. “Then ambulances arrived, they were taking up to nine people at a time. Nearly all the inhabitants of this neighbourhood ended up in the hospital,” remembers another.

“The real victim here is the Armenian citizen”

Richard Giragosian

A resident in front of a building affected by contaminated water in Nubarashen © Laurence Soustras

“The real victim here is the Armenian citizen who is actually robbed of the potential efficacy of this particular water project,” says Richard Giragosian, director of the Regional Studies Center, a think-tank based in Yerevan. “This WB project in particular contributed much to undermining the credibility and trust in the World Bank operations in Armenia, and helped foster the environment of distrust of international organisations operating in Armenia. The implementation of the project was a failure and most of the blame lies with corrupt officials in the Armenian government at that time. It is an important lesson for the World Bank, showing the importance of greater attention to transparency, especially in procurement but also in implementation, and a greater job in terms of handling the crisis.”

It is hard to say with certainty if the right lessons have been learnt. International observers maintain that high-level corruption in Armenia no longer affects international development projects. But in Yerevan rumours about dodgy dealings in projects financed by multilateral financial organisations in Armenia are rife – and they are met with general indifference. One of the collateral effects of the water scandal is that few whistle-blowers seem prepared to stick their heads above the parapets. Since Tasker ran up the red flag, two of the Bank’s projects have been investigated by INT. The first – an attempt to promote greater transparency and efficacy in the judicial system – was embroiled in a public tendering fraud scandal. Investigations into the second project found evidence of worn-out equipment destined for use in hospitals.

Kenya: ‘creative corruption’

Nairobi is the regional headquaters for many NGOs and development agencies. © Laurence Soustras

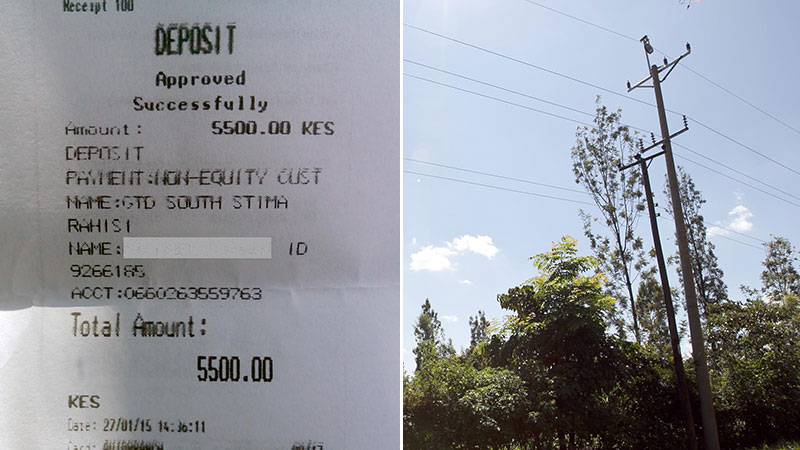

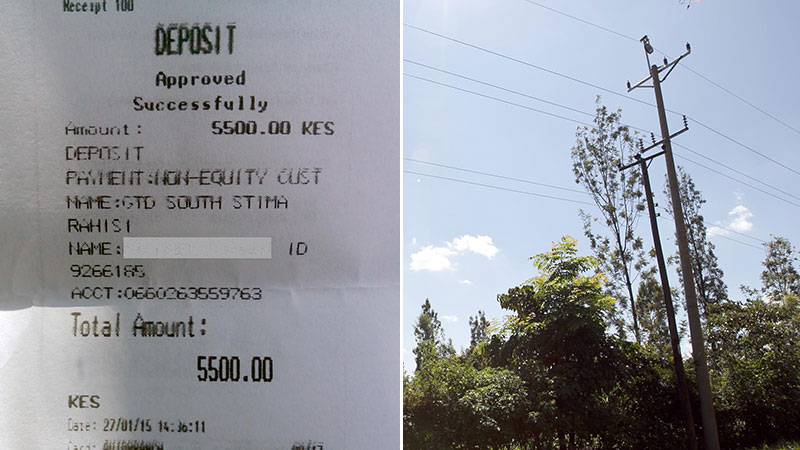

At first it seemed like welcome news: in January 2015, households in several of the poorest villages in Gatundu, a district to the north of Nairobi, were told they were finally to get connected to the electricity grid. However, after decades without electricity, it was not clear why the authorities were suddenly in such a rush. “We were told we would have to pay 5,500 shillings ($55) for wiring. In addition to that we also had to pay 1,160 shillings to get connected,” a villager recalls. “We were given a deadline and told to pay. But many people in this area are poor – they couldn’t afford to pay in such a short time and had to sell their livestock or take out loans.”

“Many had to sell their livestock or take out loans”

Stephen Mutoro

At left, a market in Gatundu. For small businesses, electricity is an economic necessity.

At right, a microfinancing centre for women in Gatundu. © Laurence Soustras

The months went by but there was no sign of the promised electricity. Then the villagers found out that poorer neighbourhoods and shantytowns around the Kenyan capital were being connected to the grid thanks to a contribution from GPOBA (Global Partnership on Output-Based Aid) – a trust fund administered by the World Bank in partnership with KPLC, the Kenyan power company. New subscribers pay a nominal connection fee of 1,160 shillings – unlike those in Gatundu. Villagers started to suspect that a local politician was embezzling their money.

Suspicions were only heightened when one of the village association’s representatives was badly beaten by the politician’s sidekicks. “The police didn’t want to get involved,” explains Stephen Mutoro, general secretary of the Consumers Federation of Kenya. “The problem is that we have this kind of World Bank giving support without improving public awareness. Criminals capitalise on the fact that people are ignorant of their rights and paying fees when they can get connected for free. Ignorance is a problem.”

“We were told that if we don’t pay by the day that was set, we won’t get electricity”

Charles Wanguhu

At left, receipt for a dubious payment. Gatundu villagers say they were the victims of extortion. © Laurence Soustras

At right, power lines, for which Gatundu residents are still waiting. © Laurence Soustras

An ill-informed beneficiary population, development aid and a widespread climate of corruption have proved to be a potent cocktail in Kenya. Charles Wanguhu, a Kenyan researcher who worked with the Africa Centre for Open Governance (AfriCOG), put it succinctly: “Donors are keen to be seen supporting a programme that works – but when they start auditing, problems start to spill out.”

And the World Bank has had its share of problems in Kenya. In 2005 the Bank temporarily suspended any new loans. Several projects (namely urban transport infrastructure and HIV/AIDS programmes) were implicated in accusations of bribery, manipulation of contracts and theft of funds. The following year the Bank’s investigative unit, INT, discovered that some of the ongoing projects were riddled with irregularities.

The Kenya Education Sector Support Programme (KESSP) was suspended by the Kenyan government in 2009, although three-quarters of the $80 million credit line granted by the World Bank had already been disbursed. A second project designed to help impoverished rural populations, the Western Kenya Community Driven Development and Flood Mitigation Project (WKCDD), suffered the same fate.

“Money goes on top and people on the ground don’t get the funds”

Charles Wanguhu

Central Gatundu © Laurence Soustras

According to a preliminary official estimate, the equivalent of €1.2 million was unaccounted for in the book-keeping of the two projects. Fifty or so Kenyan functionaries were fired and, once again, the World Bank suspended programmes in Kenya.

That same year the World Bank launched a forensic audit of transactions for the Arid Lands Resource Management Project.

http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTDOII/Resources/Kenya_Arid_Lands_Report.pdf

ALRMP had been initiated in 1996 with the aim of reducing economic and social inequalities in several districts affected by drought and desertification. The findings were shocking: more than half the transactions were judged dubious, calls for tender had been rigged, and certain expenses had been paid twice – both by the World Bank and by donor nations. Above all, the investigation lifted the lid on the flagrant collusion between staff at the Kenya Commercial Bank, project employees and civil servants. All were in league to falsify cheques or bank statements and misappropriate funds. A significant amount of money paid out in cash as part of the project’s community development programme could not be verified for lack of any paper trail.

http://africog.org/kenya-s-drought-cash-cow-lessons-from-the-forensic-audit-of-the-world-bank-arid-lands-resource-management-project/

Wanguhu, who took part in a study on the project, says: “Anything that is going to have a cash transfer feature is going to run into problems. In rural settings, it is very difficult: money goes on top and people on the ground don’t get the funds.”

The Kenyan people pick up the bill for the numerous irregularities

Gatundu residents pass beneath power lines, which remain a luxury for many Kenyans. © Laurence Soustras

In light of this litany of misappropriations the World Bank’s strategy in Kenya is, at best, unclear. Wanguhu claims: “The World Bank tries to downplay this as much as possible. They go through this cycle: ‘Let’s bypass the government, or let’s channel the funds through the government’, then there is a new scandal and they shift again. There is no institutional memory whatsoever.” For the Bank, discretion seems to be the order of the day, with the institution working to save certain projects against a backdrop of successive scandals – no doubt in the hope that they will survive the pervasive climate of corruption. Meanwhile, the Kenyan people pick up the bill for the numerous irregularities that have come to light in World Bank projects in their country. The institution’s rules specify that ineligible expenses – in other words, those that appear fraudulent – must be repaid by the beneficiary nation. Several other donor nations involved in the KESSP education project – including the United Kingdom – have also demanded refunds. All of which leaves Kenya with a hefty IOU of around $40 million for the education project alone.

Interview: Samuel Kimeu, the director of Transparency International Kenya, tells us how fraud can be beaten.

Samuel Kimeu, director of Transparency International in Kenya, argues that the solution is to increase the independence of the country’s judicial system, saying that this will, in turn, ensure that those guilty of misappropriating development funds pay the price. The Bank has given its full support for what may be a long, arduous process. Greater involvement of beneficiaries and total transparency for projects are also, he insists, prerequisites for any improvement.

FINANCE AND DEVELOPMENT:

A GRAY ZONE

“Corruption is creative,” says a World Bank official with a smile. And the Bank’s project portfolio is huge. The International Finance Corporation (IFC), the Bank’s private investment arm, lends at market rates to hundreds of financial institutions and private companies worldwide. Some are close to government-connected interests and operate in risky sectors for good governance, such as oil and extraction industries.

Funding is a gray area, with the Bank walking a thin line between development aid and international finance. IFC’s goal is to act as a gatekeeper imposing legally binding contracts and good governance. But these contracts are complex, making them difficult to monitor and hard to investigate. INT, the Bank’s anti-corruption branch, makes no secret of the fact that investigations into such loans are on the rise.

Civil society in Kenya, concerned about the potential for misappropriating oil revenues from deposits discovered in 2012, has called for the publication of the terms laid out in the exploration and development contract with the Canadian company Africa Oil, in which the IFC has invested $50 million. So far their calls have fallen on deaf ears.

“We would like to get the money back, so that those who sold their livestock can buy them back.”

A Gatundu resident

Some Gatundu residents had to sell livestock to pay for access to electricity © Laurence Soustras

Back in Gatundu the villagers are still waiting, by the light of kerosene lamps, for the electricity they were promised. And this is the least of their worries: many villagers are struggling to keep up with their loan repayments. “We don’t know where to complain, so we keep quiet,” one of the villagers said. “But we would like to get our money back so that those who sold their livestock can buy them back.”

Investigators: ‘Development Watchdogs’

World Bank headquarters in Washington, DC © Laurence Soustras

The World Bank's Integrity Vice Presidency (INT) takes up one floor of a building on the periphery of World Bank headquarters. It is, in a sense, the World Bank’s police force. The INT has 87 staff – of a total of over 12,000 people working for the Bank – and an $18.5 million budget to eradicate the “cancer of corruption” that was first diagnosed by Wolfensohn, World Bank Group president in the 1990s. INT investigators have five offences in their crosshairs: fraud, corruption, collusion, coercion and obstruction. They hunt them down on two distinct terrains: External investigations target entities working on projects with the World Bank, while internal investigations look into allegations of fraud and corruption within the Bank.

Behind the doors in an anonymous-looking corridor, accessible only by a code-locked door, INT receives a near-constant flow of rumours, suspicions and allegations concerning World Bank projects worldwide. First and foremost, the INT investigators – usually alerted by telephone or by whistle-blowers contacted by World Bank employees – must decide whether the dossier in question is within their jurisdiction. Each year fewer than 100 dossiers lead to full-scale enquiries.

“We use more and more open-source media bases and social media to identify the key players, and we had some resounding successes recently with these methods,” says Dave Fielder, external investigations manager for the Integrity Vice Presidency. “Then we move to phase two: travelling to where the project or the company is located.”

The investigators’ primary investigative tool is the audit clause. Invitations to tender for World Bank projects include a contractual obligation clause authorising the INT to audit the accounts and archives of any company bidding for a contract – even if they have been turned down. That’s where things tend to get complicated: “We look where they hope we won’t find anything. But most of the time we do find something. Most people don’t expect the World Bank to come and review their contracts, and most of the time they have never heard of INT.”

After years of unaccountability a surprise visit often pays off. “Sometimes we are fortunate and find a document with a breakdown of all the corrupt payments, or we find out that they are arranging to delete or to destroy some of the evidence that we are going after, which, in itself, is a sanctionable form of obstruction,” says an investigator.

An inquiry into development fraud at the World Bank.

INT’s mission is both to make sure the World Bank’s system of sanctions is applied to entities implicated in matters of fraud and corruption, and to inform national authorities of any offences covered by their jurisdiction. But corruption is often hard to prove legally.

“If there is a murder, there is a dead body. If there is a theft, there is money missing and it came from somewhere,” explains Steve Zimmermann, INT director of operations. “When there is corruption, usually there is a meeting between two people, cash changes hands, no one saw it, no one knows about it, the money doesn’t go to a bank account. Unless one of these two people talks, no one will ever know it happened.”

Steve Zimmermann, INT director of operations said “60 to 70% of the cases initially include corruption but it is only 30 to 40 % which include corruption at the end of the day whereas 60 to 70% involve fraud because fraud is easier to prove (*) and often that’s what you do.”

“It can be sometimes, frankly, a little overwhelming, in terms of what an institution our size is trying to do against the vast resources that we face on the other side, whether from within governments – if there are local corrupt officials involved – or from certain law firms and the accounting firms that are engaged in part in the corrupt process,” Fielder explains.

The INT has developed an ambitious programme, aimed at World Bank employees, to raise awareness of corruption. This entails collecting and sharing information on areas of risk within the Bank’s various entities to make sure projects are better thought-out – and rapidly intervening when there is evidence of fraud.

“The processes that protect whistle-blowers from retaliation are obscure”

Bea Edwards

Bea Edwards, former director of the Government Accountability Project, helps whistle-blowers at the World Bank. © Laurence Soustras

Although initially greeted with some scepticism from the Bank’s operational units, investigators have built up a constructive dialogue with employees on the ground. It is, however, too early to evaluate the project's effectiveness – namely concerning whistle-blowers within the Bank. During the 2015 financial year, 122 whistle-blowers provided the INT with information. But many argue that this is not proof that there is a sufficient climate of confidence within the institution to encourage the useful exchange of information.

“There is a very strong culture within the Bank about trying to solve things quietly and internally rather than going to the Integrity Vice Presidency,” says Chad Dobson, executive director of the Bank Information Center, a Washington-based NGO monitoring governance concerns at the World Bank. Several whistle-blowers have left the Bank – or have been encouraged to leave – following their revelations. The INT insists that this is a thing of the past. But for employees who know that their salaries and, indeed, their careers depend on a good performance evaluation, blowing the whistle on the operations of this gigantic international bureaucracy – even anonymously – may seem like a risk not worth taking. “Within the World Bank, processes for protecting a whistle-blower who makes allegations from retaliation are obscure,” insists Bea Edwards, former executive director of the Government Accountability Project, which seeks to protect whistle-blowers. In short, as a member of the institution put it, “No one wants to have problems, no one wants to lose their working visa with an international organisation and lose a decent salary.”

Somalia: ‘whistle-blowers in the wind’

Photo © Laurence Soustras

Why is it that fragile nations emerging from periods of conflict are often still in ruins, despite receiving millions of dollars in development aid? Here is Abdirazak Fartaag’s story – and a part of the answer.

As a member of the transitional government of Somalia between 2009 and 2011, Fartaag witnessed the movement of funds intended to help get the failed state back on its feet. “In those years international donors, including the World Bank, were using local groups that were not accountable to channel funds. The international community actually facilitated misappropriation of funds,” he explains.

Fartaag soon realised that government accounts often belied a tale of corruption. Since the year 2000 donor nations had been giving Somalia considerable sums of money, yet there was little or no trace of revenue or payments in the state’s accounts. Between 2000 and 2008, except for a period of two years, no expenditures were recorded in the Somalian government’s accounts. This was a clear indication of fraud at the very highest level.

In 2011 the Somalian prime minister refused to publish Fartaag’s report. When the Public Finance Unit was dismantled Fartaag took a one-way flight to Nairobi – with his report under his arm.

Like so many fragile or post-conflict nations, Somalia was awash with opaque and informal financial circuits. At that time in Mogadishu, various clans helped themselves to funds intended for development and state administration. Fartaag revealed that no one in the international donor community sought explanations for these highly visible anomalies.

When his report on Somalian state finances was published, the international development community was outraged. “They couldn’t understand how that could come from a Somali person, who was questioning the way they were doing their jobs. So they questioned my integrity,” he says.

Interview: Abdirazak Faartag, Somalian whistleblower

A year later the World Bank published its own report. The report was damning and confirmed Fartaag’s claims. Between 2009 and 2010, the Somali government had stashed away $130 million in revenue and bilateral donations – mainly received from Arab nations. According to Fartaag, Mogadishu port activities around 2009 earned between $25 and $30 million a year. Less than 25% of these earnings were recorded in state accounts.

The World Bank report pointed out that these donations would have easily paid two years’ salary for the civil servants, members of parliament and police officers who, in fact, had to be paid by the international community.

The World Bank report was not able to dispel the mystery surrounding funds from multilateral aid. The funds transited via an account held by the international auditor PricewaterhouseCoopers and should have been “accounted for comprehensively”, the report stated. They are still unaccounted for.

As a result, the former head of the Public Finance Unit saw no sign of the funds in the government budget. According to the World Bank, part of the multilateral financial institution’s aid for the 2008-2009 period was paid directly to communities in southern Somalia by local NGOs. “That is,” Fartaag points out, “in territories where you cannot implement anything without the support of groups with links to Al-Shabaab”, the jihadist terrorist group.

In 2013 the World Bank reopened financial relations with the Somali government via the Multi-Partner Fund, based on the mechanism used in Afghanistan and designed to provide budget support. But the World Bank was under no illusions, noting that Somali institutions had become “agents of extraction” for funds in their country. The United Nations Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea stated that: “corruption, embezzlement and fraud [...] have in fact become a system of management”.

So what is the best course of action in such a context? The lynchpin of the Bank’s monitoring, already used in Iraq and Afghanistan, is an external “Financial Management Agent” under contract to ensure the government in question respects regulations followed by international institutions when accounting for development aid. The World Bank set up a mechanism to limit fraud – especially where public calls for tender are concerned. The institution’s investigators recently realised that some of the audit companies working on Bank projects were themselves actively involved in circuits of fraud and corruption – either as a result of poor internal standards or straightforward collusion with corrupt officials.

However, Fartaag is not satisfied: “Somalia would be a rich country if all its revenues were accounted for,” he insists.

“Neither the government or the international community took remedial control measures to manage these funds. Nothing has been done. The international community cannot go on working from Nairobi without going outside Mogadishu airport. They must check what is implemented on the ground,” he adds.

On the ground, the beneficiary populations are less passive. In Kenya, Nicolas Seris, programme coordinator for Transparency International, notes a change in mentality: “When it comes to getting what they are due, people are more determined than they were a few years ago. Financial backers are also demanding greater transparency.”

Could the outcome be calls for demanding an inventory of development aid received by local populations? The movement is gathering pace in Africa. In eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, the Chirezi Foundation has set up brigades composed of representatives elected by local communities to inspect development projects twice a month. Any problems are duly noted and the foundation contacts donor organisations, on behalf of the communities, to find a solution.

In Kenya, Transparency International trained 150 representatives from local communities to use social auditing techniques to monitor projects. In collaboration with 40 or so donors, as well as local and international actors, the organisation also set up an internet platform, an SMS number and a single form to centralise complaints related to projects. The practices could easily be adapted to even the biggest multilateral organisations, so long as beneficiary populations are well informed about approved funding and have access to a complaints procedure. Above all, as Seris puts it, “people must be confident that something will be done if they take the risk of speaking out”.

(*) Stealing from development projects accounts by making payments based on fraudulent invoices is a widespread illicit practice and is easier to substantiate than corruption itself