Syria is mired in not one but several conflicts that have ravaged the Middle Eastern country for more than five years. What began as a localised protest movement has morphed into a nationwide conflagration involving multiple forces, including major foreign powers. FRANCE 24 takes a look at the key players and alliances.

The ceasefire brokered by the US and Russia on September 9 – described by Washington as the “last chance to save Syria” – has collapsed, as have all previous attempts to end the protracted war. Over the years, the popular uprising that began in March 2011 in the southern city of Deraa has evolved into a complex, multifaceted conflict involving a range of combatants, both Syrian and foreign, with competing agendas. The human cost has been colossal: more than 300,000 dead and thousands more missing; millions of internally displaced and millions more refugees abroad; a landscape ravaged; and an economy in ruins.

The regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad is battling a multitude of evolving rebel factions, many jihadist, and many backed by powerful foreign patrons. The divisions plaguing the rebel cause have precipitated the rise of the Islamic State (IS) group, which has conquered large swaths of the country. Its expansion has triggered the formation of a vast international coalition, which is carrying out a targeted bombing campaign against the jihadist group. The coalition is led by the US and features several Western powers, including France, as well as Middle Eastern countries such as Jordan. Meanwhile, Syrian Kurds have emerged as a potent force on the battlefield, in the process seizing more autonomy than ever before in Syria.

After five years of insurgency and counter-insurgency, what is the situation on the ground? Who are the main combatants, and what alliances are at play?

Why has Turkey intervened?

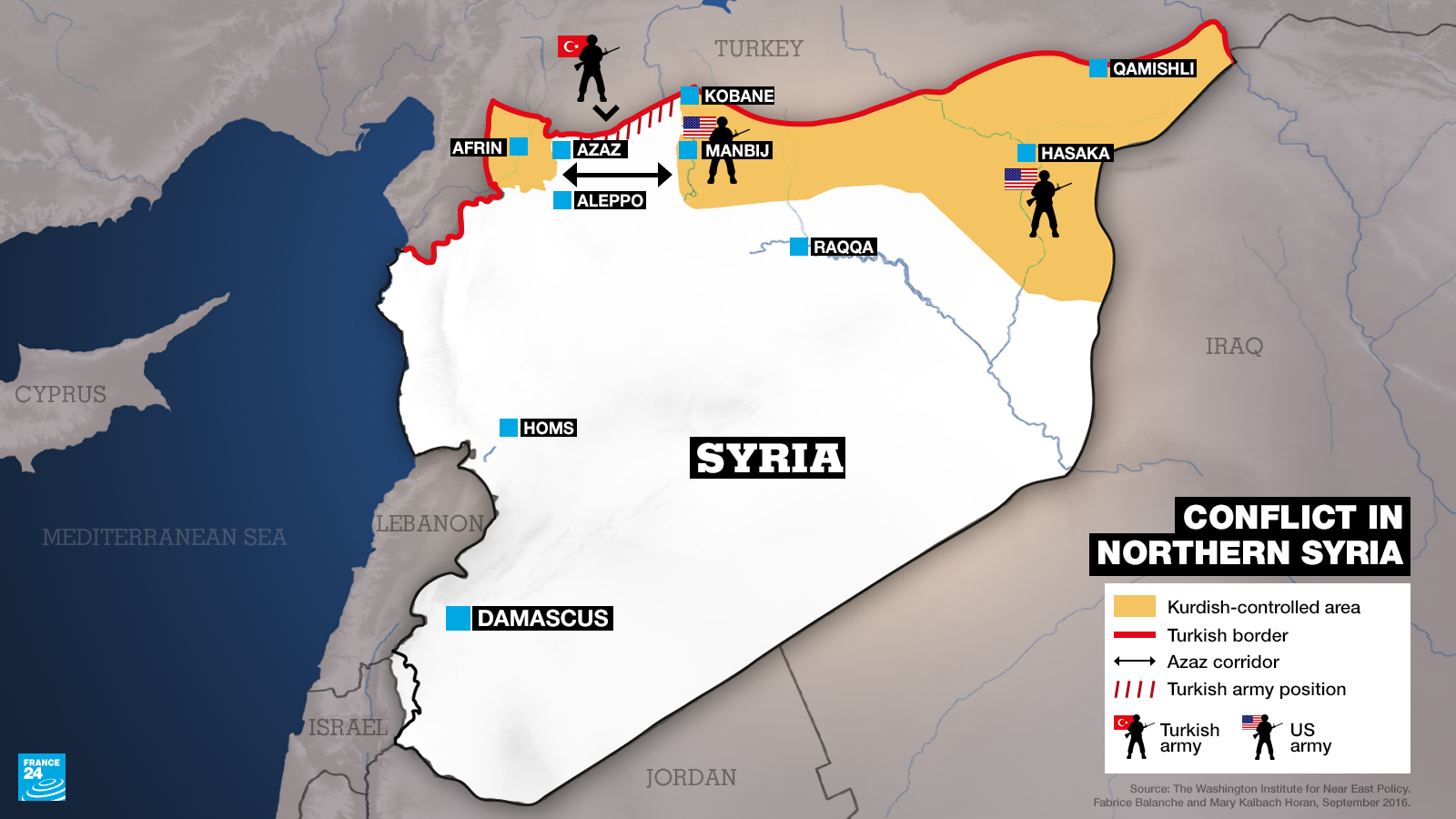

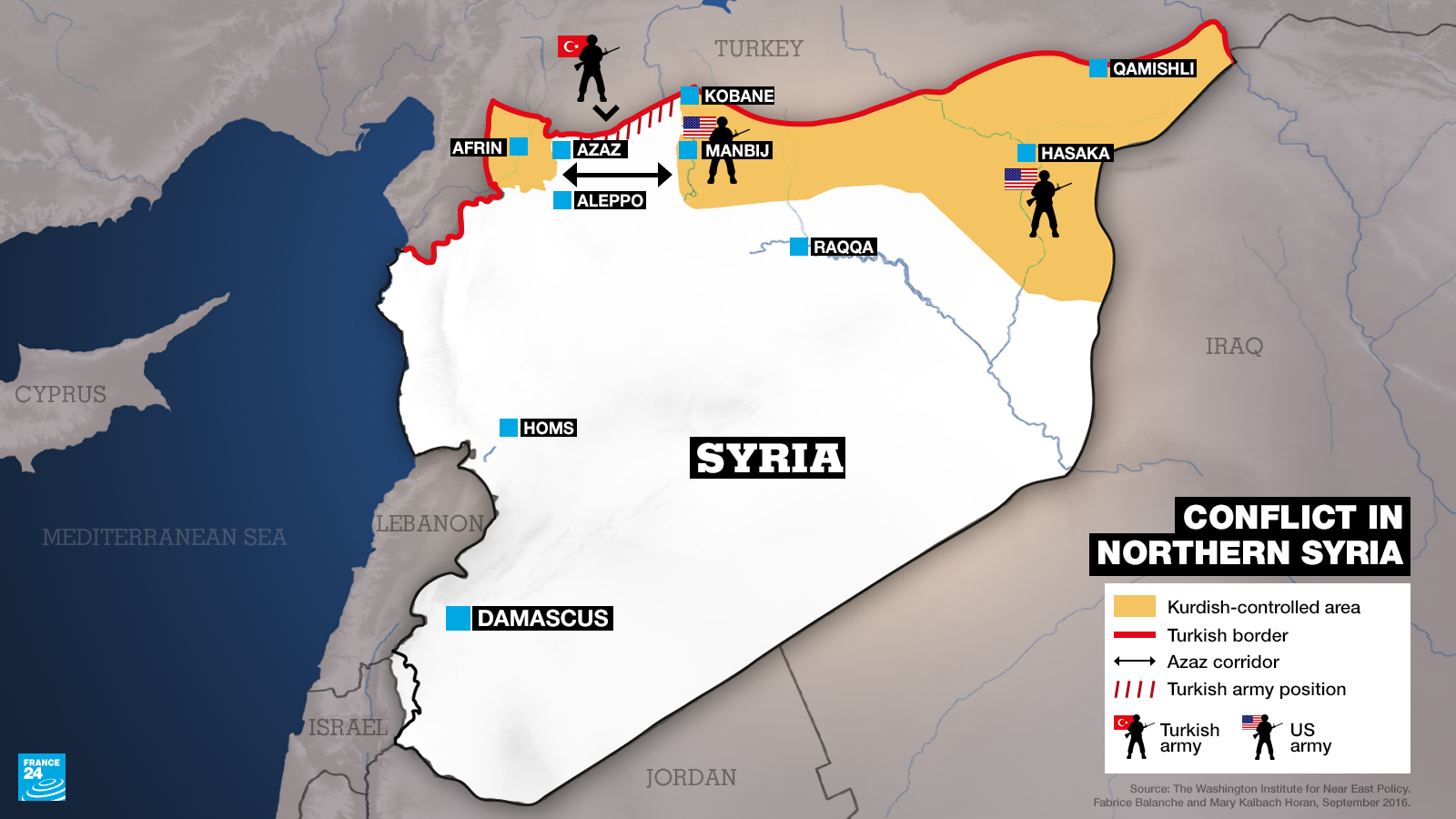

With the launch of Operation Euphrates Shield in August, Turkey has officially joined the battle against the IS group on Syrian territory. But “Turkey’s real purpose is to halt the territorial expansion of Syrian Kurds,” says Fabrice Balanche, a Syria expert and visiting fellow at The Washington Institute.

On September 19, the government in Ankara said Turkish-backed rebels would push their offensive further south into Syrian territory. “As part of Operation Euphrates Shield, an area of 900 square kilometres has been cleared of terror so far,” said President Recep Tayip Erdogan. “We may extend this area to 5,000 square kilometres as part of a safe zone," he added.

Turkey’s advance relies on a variety of rebel groups including the al-Zinki Brigade; the Sultan Murad Brigade, which is largely made up of ethnic Turkmen considered loyal to Ankara; and groups linked to the Muslim Brotherhood such as Jaish al-Islam, formerly known as Liwa al-Islam.

What do the Kurds want?

Syrian Kurds control most of the country’s northeast. Since the start of the conflict, the Democratic Union Party (PYD), a local affiliate of Turkey’s historic foe, the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), has fought off all attempts to encroach on its territory, whether by loyalist or rebel forces.

Since regime forces pulled out of the region in the early stages of the war, Syrian Kurds have acquired the de facto autonomy Damascus had always refused to grant them. But in some cases Kurdish forces have struck alliances of convenience with the regime, most notably in Aleppo.

The battle for Hasaka, which saw government planes bomb Kurdish forces in August 2016, is a case apart. The deadly clashes in the northeastern city followed Kurdish attempts to seize control of government buildings and eject representatives of the central government. “That is unacceptable to Damascus, and it took a Russian mediation to end the fighting,” says Balanche.

Kurdish military victories over jihadist groups have allowed the PYD to all but link up Syria’s three Kurdish enclaves: Afrin, Kobane and Qamishli. This has alarmed neighbouring Turkey, which is desperate to prevent the establishment of a Kurdish autonomous region along its border.

Why is Russia supporting the Kurds?

Syria’s Kurds have shrewdly exploited foreign powers’ varying objectives to advance their own cause. With Washington’s help, they chased the IS group out of the city of Manbij, located outside their traditional territory. And in the strategic Azaz corridor, seen as crucial to link up Kurdish enclaves along Syria’s northern border, they were backed by Russia.

“[Russia’s Vladimir] Putin sees Kurdish nationalism as the only factor capable of changing the rules of the game in the Middle East and, especially, weakening Turkey,” explains Fabrice Balanche. Furthermore, the Kurds are seen as excellent border guards, whereas a porous northern border that allows rebel fighters, jihadists and ammunition to move freely is a major obstacle to Syrian and Russian hopes of reconquering the country.

Why is the US helping the Kurds?

Washington regards the PYD’s military arm, the People’s Protection Units (YPG), as the most reliable partner on the ground in the fight against the IS group. All other US attempts to arm and train rebel units have failed miserably. These include the 13th Division and the Hamza Brigade, at one stage “vetted” and armed by Washington, which were routed by the jihadist al-Nusra Front and deprived of their US-made TOW missiles.

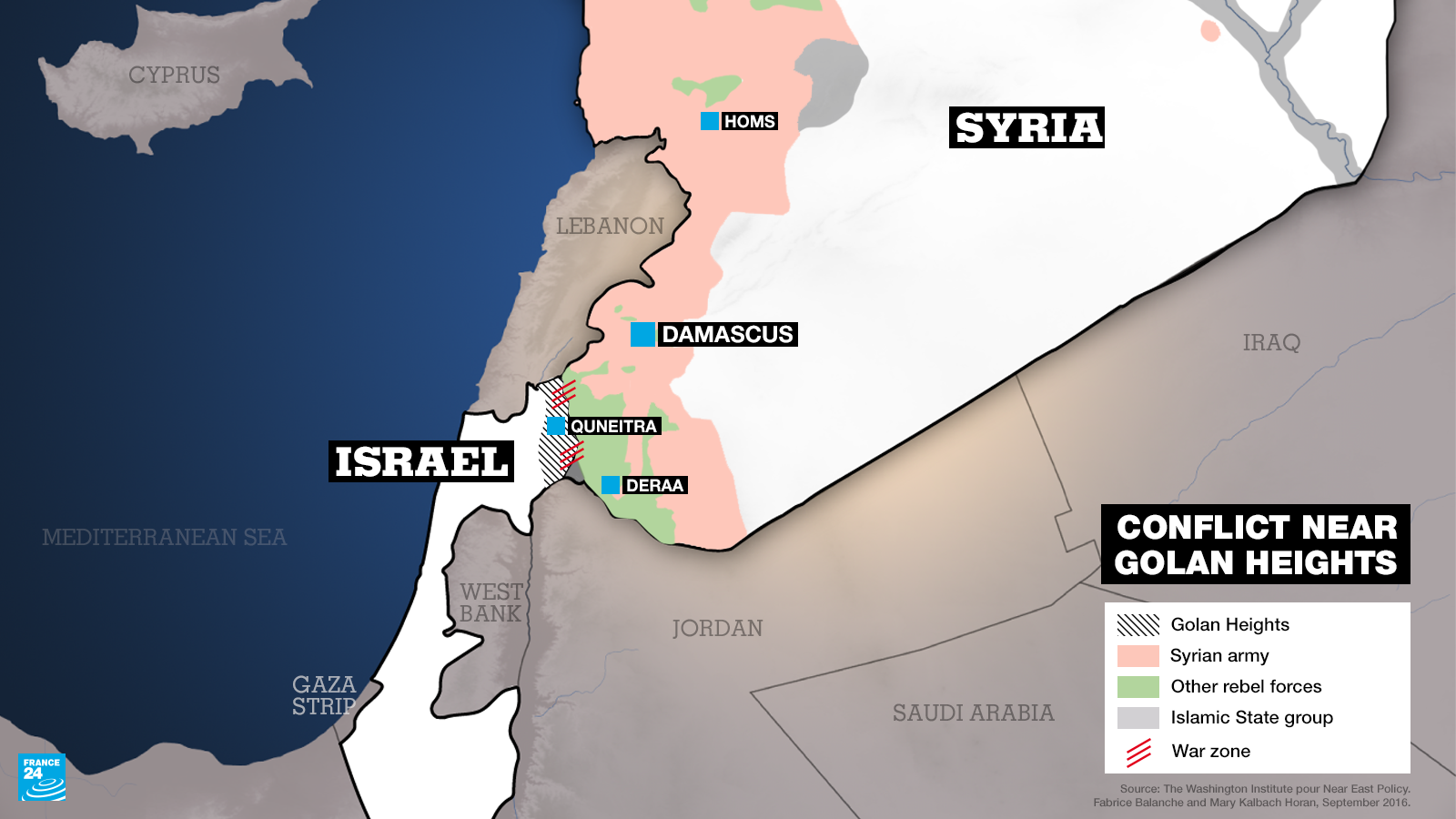

How does Israel view the conflict?

The Syrian conflict has long been a subject of debate in Israel, which shares a border with the war-torn country. “On the one hand, some argue that Assad’s fall would weaken Iran, Israel’s main enemy. But, on the other hand, the prospect of Islamist groups seizing control of Syria is somewhat worrying,” says Balanche.

Israel is determined to protect the Golan Heights, a disputed border territory it seized from Syria in 1981. Since the start of the conflict, rockets fired from Syria have routinely landed in the Golan, though it is not clear whether regime or rebel forces are to blame. Each time Israel has responded by firing into Syria.”Obviously, if Iranian forces or their Lebanese allies Hezbollah were to exploit the Syrian conflict to position themselves around the Golan, then the Israeli government would intervene,” says Balanche.

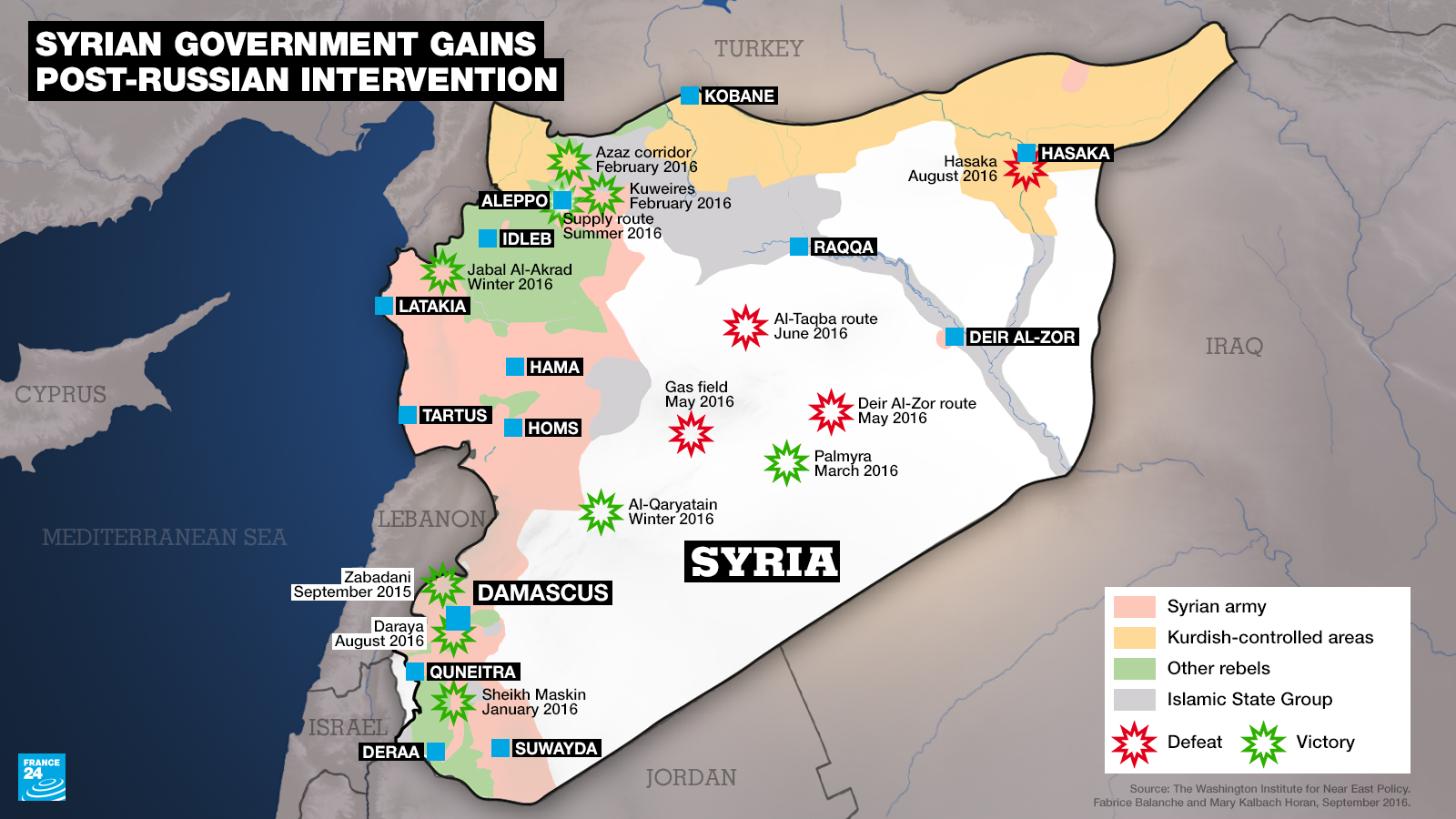

What is Russia’s strategy?

Russia’s military formally intervened in Syria on September 30, 2015, following a request by Assad, whose troops had suffered a string of defeats. The Russian army has a strategic base on the Syrian coast, in Assad’s western stronghold. It has built a second, smaller base in the ancient city of Palmyra, which it helped liberate from IS group forces in March 2016.

Moscow’s interests in Syria are not limited to maintaining the Assad regime. Russia aims to encircle Turkey, the recent public reconciliation between Putin and Erdogan – magnified by the media – having merely sanctioned a normalisation of relations between two regional rivals. In siding with Assad’s other key ally Iran, Putin also hopes to put pressure on Tehran’s foe Saudi Arabia, Russia’s biggest rival in the highly competitive oil market.

Can Assad’s regime survive?

When Washington and Moscow announced the latest ceasefire deal in September, Assad was busy blowing hot and cold – officially endorsing the truce, while vowing to reconquer all of Syria. The embattled president also warned that he would hit back should his forces come under fire from “terrorists”, a term his regime has applied indiscriminately to all rebel groups since the start of the conflict. Barely four days into the ceasefire, the bombing resumed in the suburbs of Damascus and the section of Aleppo still held by the rebels.

Aleppo, once Syria’s most populous city, is crucial to Assad. His regime plans to grant Kurdish forces a de facto autonomy, and other parts of the country will no doubt continue to elude its control. But state institutions continue to function, including in rebel-held areas. “It is part of the regime’s counter-insurrection strategy,” concludes Balanche.