It's T-minus zero for French astronaut Thomas Pesquet. The 43-year-old space veteran lifts off on Friday, bound for the International Space Station (ISS) aboard SpaceX's Crew Dragon capsule. The six-month mission, named Alpha, is a historic first as Pesquet will become the first French commander of a space station.

Thomas Pesquet: "Practising our scales to work our way to the moon"

On Monday, four days before lifting off for the International Space Station, Thomas Pesquet spoke to FRANCE 24 and RFI from Cape Canaveral, Florida. The French astronaut will travel to the ISS alongside one Japanese and two American companions on the SpaceX Crew Dragon. Once he arrives on the station, Pesquet's daily routine should look a lot like his first mission in space in 2016 and 2017.

"A lot of things will be similar, notably the research – conducting scientific experiments that we wouldn't be able to carry out on Earth – and preparing for the next stages of space exploration, which every day takes on more and more importance aboard the station," Pesquet explains. "It's a way to practise our scales to work our way towards the moon, towards Mars. For sure, that is everybody's goal."

This Alpha mission will also include new elements since the Frenchman will take command of the ISS for a month, a first for a French astronaut and "recognition for a European", as he puts it. "Now, I have the experience, I'll have the opportunity and the honour to be commander of the station during the second half of my mission. That mainly means being in a leadership role and passing along that experience that I received during the course of my first mission," Pesquet says.

Once on board the ISS, Pesquet is slated to conduct a number of the 232 scientific experiments planned for this mission. "There is one that is really exciting," he says. "We are going to study mini-brains, stem cells – we can't yet imagine the applications that that can have." Four spacewalks are also on the agenda. "I might have the chance to do one or two of them," Pesquet says. The objective of those ventures outside the space station "will be to improve the station's electrical system of solar panels. The oldest of the ISS's modules are now about 20 years old and the generation of electrical power is a bit limited in relation to the station, which has grown."

Preparations for Mission Alpha

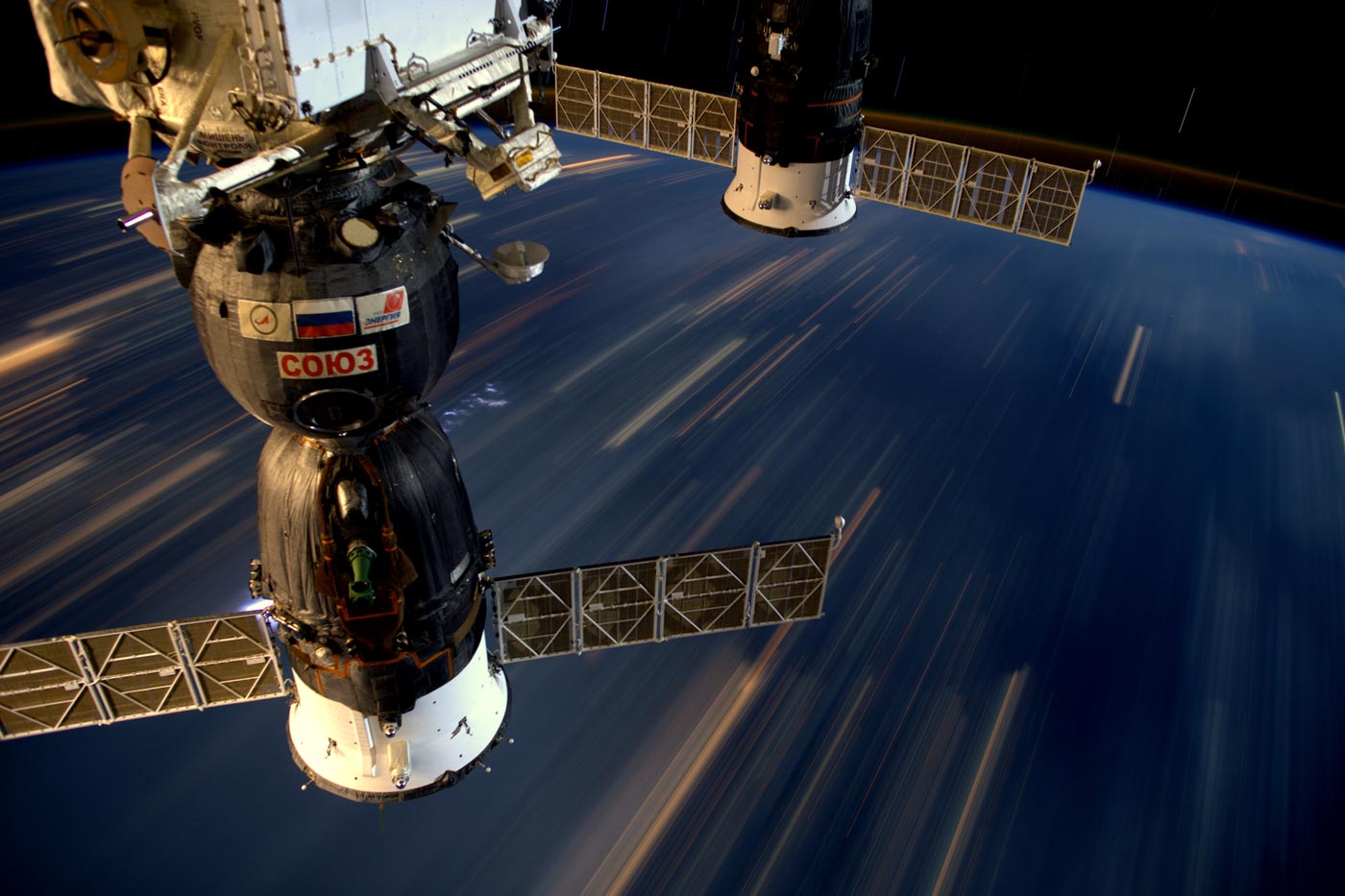

SpaceX, the American company founded by Elon Musk in 2002, has become a major player in the space race. Fully grasping the success of SpaceX requires a look back at the genesis of the International Space Station, first launched in 1998 to receive the US Space Shuttles as well as Russian Soyuz rockets.

But the explosion of the Space Shuttle Columbia upon its return to earth in February 2003 was an inflection point. The seven astronauts on board were killed in the disaster and, for two-and-a-half years, US Space Shuttle missions were halted. In 2011, the Space Shuttle was withdrawn from service and NASA decided to let private sector players compete to convey astronauts and cargo to the ISS.

SpaceX won that challenge with its Dragon spacecraft and Falcon 9 launch vehicle. The company's first operational flight to the ISS was a success in May 2012. Since then, Falcon 9 has completed 110 launches, significantly outpacing its competitors; in 2020, only China performed more space launches than SpaceX. The American firm's innovation lies in its use of a reusable launch system that drastically reduces costs thereby permitting more launches. And it worked: in 2020, for example, SpaceX used only five new launchers for its 25 flights.

As for Mission ALPHA, the Crew Dragon capsule being used already served for a flight last year and the launcher was used to send the previous crew to the ISS in October 2020. On April 22, Thomas Pesquet will become the first European to fly with SpaceX.

France's space travellers

Pesquet is the tenth French astronaut to travel to space. The country's place in the space race stretches back six decades. In 1961, France became the third nation to establish a space agency, the National Centre for Space Studies (CNES), and to launch its own rocket programme; in 1963, France successfully sent an animal into space, astro-cat "Félicette". The space-travelling feline's flight lasted 13 minutes and she lived to tell the tale, so to speak.

Then came the humans' turn. In 1982, Jean-Loup Chrétien became the first Western European to leave Earth: his nine days aboard Russia's Salyut 7 station were the result of direct negotiations in 1980 between French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing and his Russian counterpart, Leonid Brezhnev. The next Frenchmen to complete missions into space were Patrick Baudry, Michel Tognini, Jean-Jacques Favier, Léopold Eyharts and Philippe Perrin. In 1996, Claudie Haigneré became the first, and so far only, Frenchwoman to travel into space. Jean-Pierre Haigneré, Claudie's husband, became the first French astronaut to carry out a long-term mission when he spent six months aboard Russia's Mir space station in 1999.

Astronaut Jean-François Clervoy, for his part, flew three missions with NASA. "Even if you've seen photos and footage of Earth from space, when you go to the porthole for the first time, and you see it with your own eyes ... it's like a jewel, more beautiful than the greatest of paintings by the greatest painter in history," Clervoy would later say.

Pesquet rounds out the list of French space travellers, putting France in the same range as Canada, Germany, Italy and China – and still a world away from the 340 astronauts the United States has sent into space. For his second spaceflight, during a segment of the Alpha mission, Pesquet will become the first French and first European astronaut to command the International Space Station.

The International Space Station's uncertain future

Although entirely dedicated today to scientific research, the International Space Station was at the outset a political tool. The idea was launched to create the International Space Station in the United States in 1984 by then-president Ronald Reagan. "Tonight, I am directing NASA to develop a permanently manned space station and to do it within a decade," Reagan announced during his State of the Union address that January.

Still, the project remained at a standstill into the 1990s while the US prioritised its Space Shuttle programme. But in December 1991, the Soviet Union was dissolved; its space programme was abandoned and many of its engineers – missile specialists – were at a loose end. For the West, allowing those engineers to sell their services to the highest bidder – just as countries like Libya, Iran and North Korea were seeking to develop their nuclear programmes – was out of the question.

"There was a fear that the skills on the Russian side would be siphoned off a bit," explains Lionel Suchet, CNES's Chief Operation Officer. With the aid of the skills Russians acquired through the launch and exploitation of eight orbital space stations, the seven Salyuts and Mir, the International Space Station project was resuscitated. A cooperation agreement was signed between the American, Russian, European, Canadian and Japanese space agencies in 1993.

The assembly of the ISS began on November 20, 1998, at an altitude of 400 km. The station consists of 16 attached modules, or 900 m3 (400 m3 of which are inhabitable) and 2,500 m2 of solar panels. The station weighs about 400 tonnes and covers an area as large as a football field: 100 metres long, 74 metres wide and 30 metres high. It is the largest artificial object in orbit. It took some 13 years to assemble.

The International Space Station passes over our heads at 27,600 km/h, a speed that keeps the structure from falling to Earth and that allows the astronauts inside to operate at zero gravity. The ISS does need to be lifted now and again so that the station stays on its orbit, using the ATV cargo vessel, which gives it a boost of speed. Each space agency is a proprietor of the ISS in relation to its contribution to the station and there is a very regimented system of exchanges in place.

The ISS has been permanently inhabited since October 31, 2000, and the station is slated to remain so for a long time. Its operation was recently extended through to 2030.

During Pesquet's first mission, Proxima (2016-2017), his tasks largely consisted of experiments, physical exercise, some observation and a lot of maintenance operations. For his return to the ISS four years on, the Frenchman will perform similar tasks, in the same order. A day on the space station is, after all, made up of a succession of meticulously timed operations. Astronauts have little free time on board. To reduce the effects of weightlessness on their bodies, they must undertake 90 minutes of sport a day, six days a week. Then comes the scientific part. Pesquet himself is the subject of one experiment: every journey serves to observe more and more acutely the effects of weightlessness and radiation on the human body, with an eye to preparing future, more distant voyages, notably to Mars.

The French astronaut will also carry out a number of science experiments: on cold plasma, which could serve to better fight illnesses resistant to antibiotics; on protein crystals, to fight certain kinds of myopathy; as well as on antimicrobial metals. Pesquet will also study the ageing of the brain. Astronauts spend a total of 36 hours a week conducting research.

L-6 As we are preparing for #MissionAlpha launch I think back to 2008 and what would have happened if I didn't apply to be an astronaut 😳. The most selective phase in the selection... is whether you choose to apply or not (it’s true!). After that the rest is easy... or almost 😅 pic.twitter.com/nrWpm14924

— Thomas Pesquet (@Thom_astro) April 16, 2021

The rest of the time, astronauts must do maintenance. The ISS needs upkeep and the majority of its components have a programmed obsolescence of 15 years. That is where the mission priority lies for those who come on board: maintain the station in its best possible condition to extend the station's lifespan for as long as possible. While that part of the mission can be mundane, it is also the part that affords the most exciting moments for astronauts on the ISS, notably during extravehicular activities or spacewalks.

Pesquet believes his next spacewalk will be an ambitious one: he is due to trek all the way to the end of the station, via the outside, in order to install new solar panels that will boost the production of electricity.

Although the end of the ISS's lifespan is forecasted regularly, the station recently saw its mission prolonged until 2030, the use-by date for which its oldest components are certified. "Certain modules will become obsolete over the next 10 years because there were certified for 30 years. So the obsolescence is technical and there are replacement solutions, either for elements or for whole modules. That's a possibility and then we could keep going for another decade," says Didier Schmitt, the European Space Agency's strategy and coordination group leader for human and robotic exploration.

Currently, the priority is on maintenance of the ISS. And it isn't a coincidence that astronauts spend half of their time on board maintaining their habitat. Leaks have already begun to appear, one of which was plugged with sticky tape after it was detected with the help of floating tea leaves released from a teabag.

According to the space station's critics, the ISS costs too much – about $150 billion has been sunk into the station. Detractors say the station is archaic and that the original message of reconciliation between the West and Russia that it was once supposed to convey has had its day. But getting rid of the ISS isn't all that simple. Having the station disintegrate in the atmosphere, as Mir did, would require dismantling it in space and making multiple return trips. Another solution would be to divide the station into several parts and reuse them and or sell them on to the private sector.

For now, the choice made is for continuity. Elements on their last legs will be replaced as necessary and the ISS will continue to serve as a laboratory for learning everything possible about life in a zero-gravity environment with an eye to better preparing future journeys to Mars.

Finally, the years to come will see space tourism developed on board the ISS. Some US firms even envisage adding their own module to the space station to send tourists up. A trip will cost upwards of €50 million.