Simone Veil addresses protesters outside the European Parliament in Strasbourg on March 25, 1980. © Dominique Faget, AFP

Simone Veil, the revered French politician who survived the Nazi death camp at Auschwitz and defied institutional sexism to push through a law legalising abortion in France, has died on June 30th 2017. She was 89.

In the shadow of war

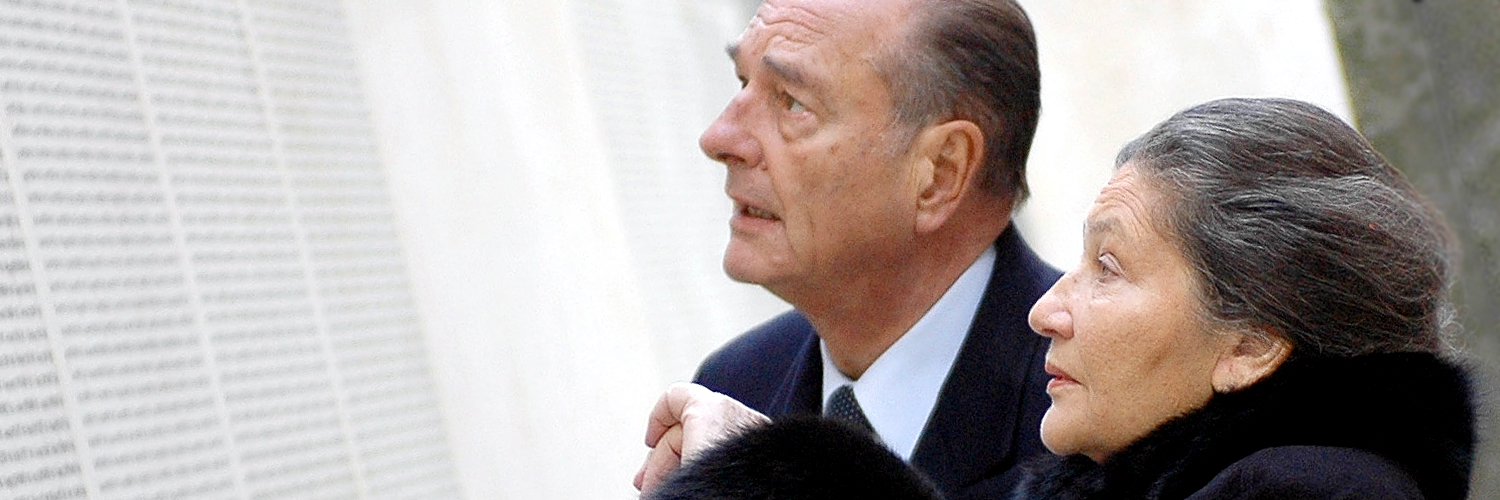

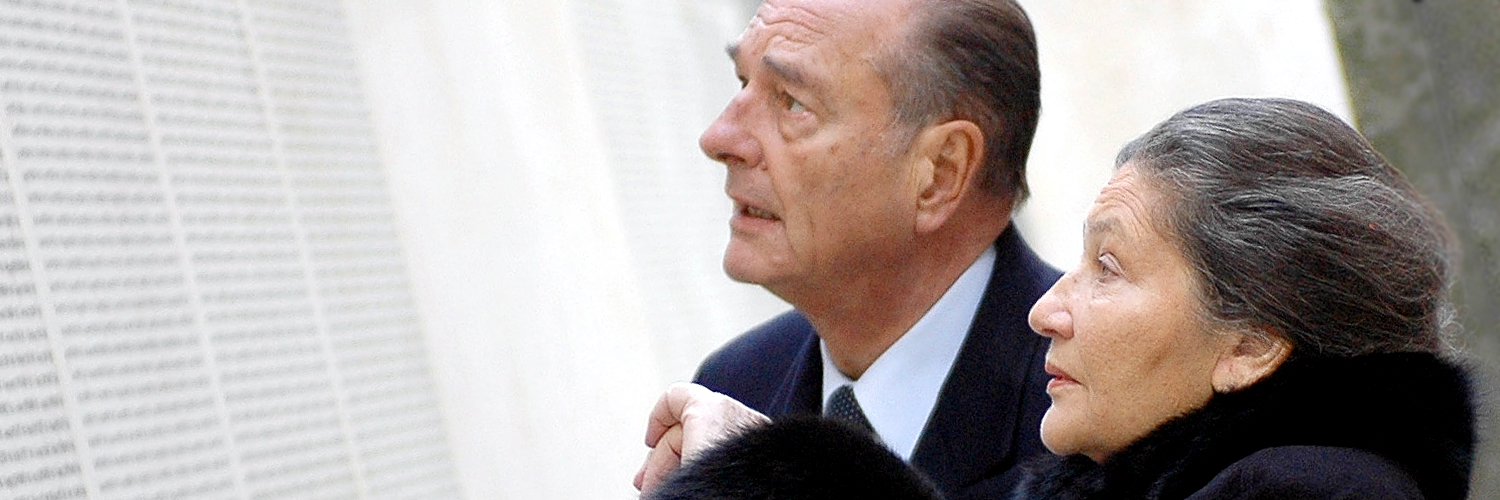

Simone Veil and former French president Jacques Chirac stand before the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris on January 25, 2005. The wall bears the names of Jews deported from France to Nazi death camps during World War II. © Jacques Brinon, AFP

A widely respected figure across the political divide, Veil was the first female leader of the European Parliament and the recipient of France’s highest distinctions, including a seat among the “Immortals” of the Académie française, the prestigious state-sponsored body overseeing the French language and usage. She was renowned for her endeavours to advance women’s rights and the gracious but steely resolve with which she overcame male resistance throughout a remarkable life scarred by personal tragedy.

As one of the more than 76,000 Jews deported from France during World War II, Veil appears on the Wall of Names at the Shoah Memorial in Paris, under her maiden name Simone Jacob. So do her father André, her mother Yvonne, her sister Madeleine and her brother Jean. Of the five, only Madeleine and Simone survived the ordeal, though Madeleine would die in a car crash just seven years after the war.

Simone was the youngest of four siblings, born in the French Riviera resort of Nice on July 13, 1927, in a family of non-practising Jews. Her father, an award-winning architect, had insisted her mother abandon her studies in chemistry after they married. Like most other Jews in France, he reluctantly obeyed orders once the Nazi-allied Vichy regime came to power in June 1940, registering his family on the infamous “Jewish file” – which would later help French police and the German Gestapo round up France’s Jews and deport them.

As French nationals living in the Italian occupation zone, the Jacob family avoided the first round-ups, which targeted foreign Jews, mainly in the northern half of France that was occupied by German troops. But they suffered the sting of anti-Semitic laws, which forced André Jacob out of work and led to Simone adopting the name Jacquier to conceal her origins.

The situation worsened after September 1943, when the Nazi occupiers swept all the way down to the Riviera. Simone, then aged 16, had only just passed her baccalaureate when she was arrested by two members of the SS on March 30, 1944. The Gestapo soon rounded up the rest of the family with the exception of Simone’s sister Denise, who had joined the Resistance in Lyon. Denise would later be detained and deported to the Ravensbruck concentration camp, from where she returned after the war.

Number 78651

Simone Veil walks alongside former French president Jacques Chirac (right) and writer Marek Halter (left) at a ceremony marking the 60th anniversary of the liberation of the Nazi concentration and extermination camp at Auschwitz, on January 27, 2005. © Patrick Kovaric, AFP

While Denise was treated as a resistance fighter, Simone and the rest of the family were forced to suffer the fate reserved for France’s Jews during that dark period in history. The women were deported to Auschwitz, the largest of the Nazi death camps, on April 13, 1944, arriving after a ghastly three-day journey trapped in an overcrowded cattle cart. A month later, André and Jean boarded Convoy 73, the only train from France to head for the Baltic States. Simone would never hear from them again.

Youths of her age were normally sent straight to the gas chambers at Auschwitz, but Simone lied about her age, heeding the advice of an inmate who spoke French. She was registered for the labour camp, shaved from head to toe and tattooed with the serial number 78651 on her arm. "From then on, each of us was just a number, seared into our flesh," she recalled years later in her memoirs. "A number we had to learn by heart, since we had lost all identity."

"Each of us was just a number, seared into our flesh"

Simone Veil in her memoir, 'A Life'

For several months, Simone, her mother and her sister endured the ritual humiliation and hellish work routine of deportees, lifting boulders, digging trenches and building embankments – all the while battling to stay upright and avoid the dreaded gas chambers. When Auschwitz was evacuated in January 1945, as Soviet tanks approached, they took part in the grisly “death marches”, eventually reaching Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, where Simone worked in the kitchens.

On March 13, the typhus epidemics that raged through Nazi camps took Yvonne’s life. Madeleine also fell ill, but was saved in extremis when Allied troops liberated Bergen-Belsen on April 15. When a British officer asked an emaciated Simone her age, she told him to guess. “He said I must be in my 40s,” she later recalled. “No doubt he thought he was being polite.”

The cause of women

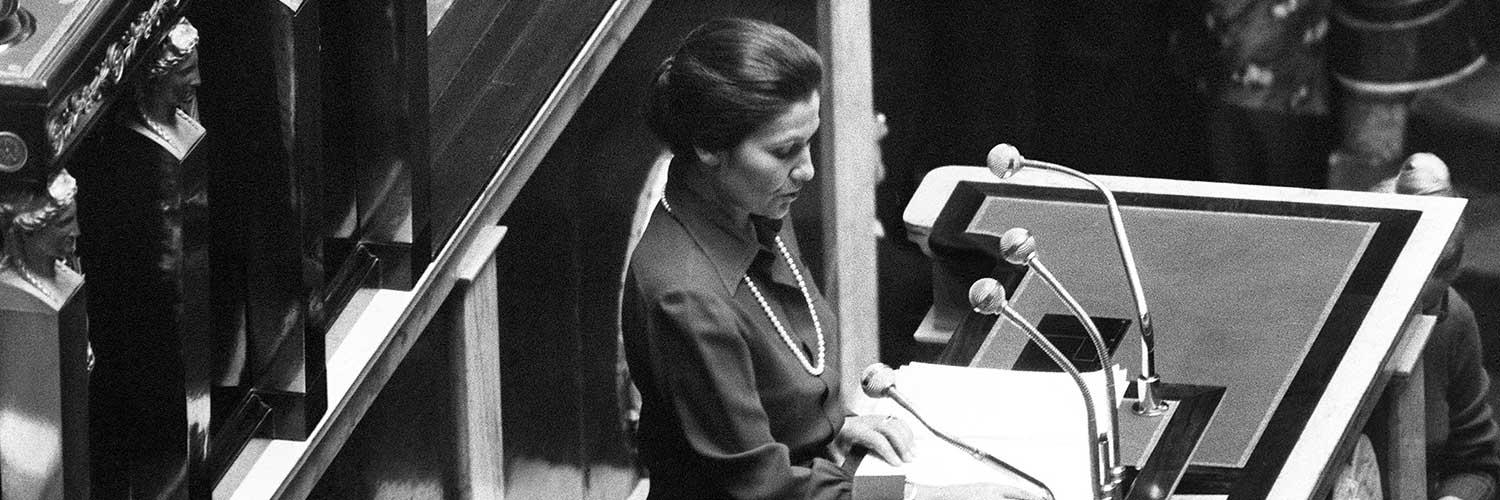

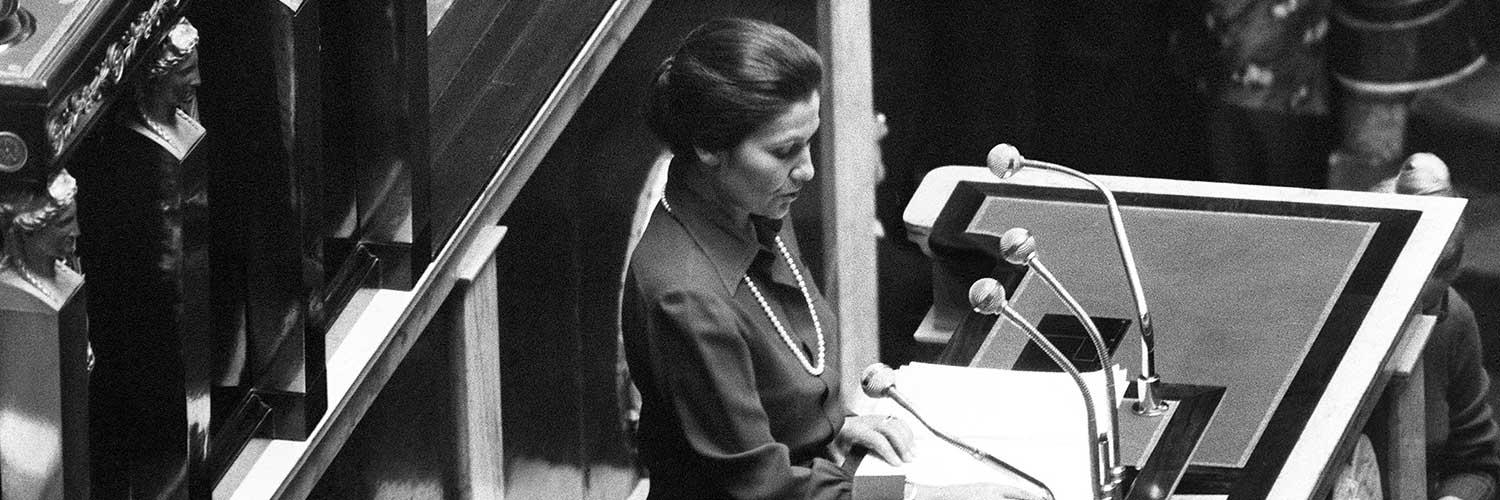

The health minister addresses France's National Assembly on November 26, 1974, defending her bill to legalise abortion in France. © AFP file photo

Still only 17, Simone returned to France devastated by the loss of her parents and sister, but determined to pursue the career her mother had been denied. She studied law at the University of Paris and the Institut d’études politiques, where she met Antoine Veil (1926-2013), a future company manager and auditor. The couple married in October 1946, and would go on to have three sons, Jean, Nicolas, and Pierre-François.

Simone Veil began work as a lawyer before successfully passing the national examination to become a magistrate in 1956. She then took on a senior position at the National Penitentiary Administration, part of the Ministry of Justice, thereby securing a first platform to pursue a lifelong endeavour of advancing women’s rights. She notably strove to improve women's conditions in French jails and, during the Algerian War of Independence, obtained the transfer to France of Algerian female prisoners amid reports of widespread abuse and rape.

Switching to the ministry’s department of civil affairs in 1964, Veil continued to push for gender parity in matters of parental control and adoption rights. A decade later, her appointment as health minister in the centre-right administration of President Valéry Giscard D’Estaing paved the way for her biggest political test. She first battled to ease access to contraception, then took on a hostile parliament to argue in favour of a woman’s right to have a legal abortion.

“No woman resorts to an abortion with a light heart. One only has to listen to them: it is always a tragedy,” Veil said in a now-famous opening address on November 26, 1974, before a National Assembly almost entirely composed of men. She added: “We can no longer shut our eyes to the 300,000 abortions that each year mutilate the women of this country, trample on its laws and humiliate or traumatise those who undergo them.”

Simone Veil's opening statement at the National Assembly defending her bill to legalise abortion in France. (video in French)

After her hour-long address, the minister endured a torrent of abuse from members of her own centre-right coalition. One lawmaker claimed her law would "each year kill twice as many people as the Hiroshima bomb”. A second berated the Holocaust survivor for "choosing genocide". Another still spoke of embryos "thrown into crematorium ovens".

“I had no idea how much hatred I would stir,” Veil told French journalist Annick Cojean in 2004, reflecting on the vitriolic debate decades earlier. “There was so much hypocrisy in that chamber full of men, some of whom would secretly look for places where their mistresses could have an abortion.”

The bill was eventually passed, thanks to support from the left-wing opposition, though Veil had to withstand the affront of swastikas painted on her car and home. Today, the “loi Veil” enjoys overwhelming support in France, where few mainstream politicians dare to challenge it.

The cause of Europe

Simone Veil gives a speech at the European Parliament in Strasbourg on July 24, 1984. © Michel Mochet, AFP

Veil dedicated much of the latter part of her political career to the cause of European integration, leaving the government in 1979 to stand in the first direct elections for the European Parliament. She won the first of three consecutive terms that year, and became the parliament’s first female president, a post she held until 1982.

After returning to her job as health minister between 1993 and 1995, Veil was appointed to France’s Constitutional Council, the country’s highest constitutional authority, three years later. In 2005, she put herself on leave from the council to campaign for a “yes” vote in a referendum on Europe’s constitutional treaty – a move that drew criticism because it contravened the council’s rules on political neutrality. When the “no” won in a shock result, she lamented a “catastrophe” for both France and Europe.

In the run-up to the 2007 presidential election, Veil surprised many observers by coming out strongly in favour of right-wing candidate Nicolas Sarkozy. However, she openly criticised his decision to set up a Ministry of Immigration and National Identity. She also took a position against Sarkozy’s controversial proposal to make every 10-year-old school child honour Jewish child victims of the Holocaust, calling it, “unimaginable, unbearable, dramatic and, above all, unfair”.

In 2008, Sarkozy changed the rules governing the Legion of Honour, France’s top distinction, to ensure Veil could be awarded the medal of Grand Officer without going through the lower orders. The same year, she was elected to the Académie française, becoming only the sixth woman to join the prestigious “Immortals”, who preside over the French language. Her ceremonial sword was engraved with the motto of the French Republic (“Liberty, Equality, Fraternity”), that of the European Union (“United in diversity”), and the five digits tattooed on her forearm in the inferno of Auschwitz, which she never removed.

Simone Veil enters the Académie française on March 18, 2010, accompanied by her son Jean. Veil was elected to the prestigious body in November 2008, becoming only the sixth woman to join the "Immortals". © François Guillot, AFP