On July 1, 1916, the British and French armies launched a major offensive against German lines in the Somme region of northern France. Over the ensuing five months, a brutal battle of attrition left more than one million people of all nationalities dead, wounded or missing. To mark the centenary of the Great War's deadliest battle, FRANCE 24 asked staff members to recall their ancestors' role in those fateful events.

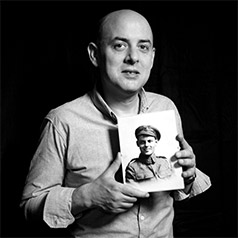

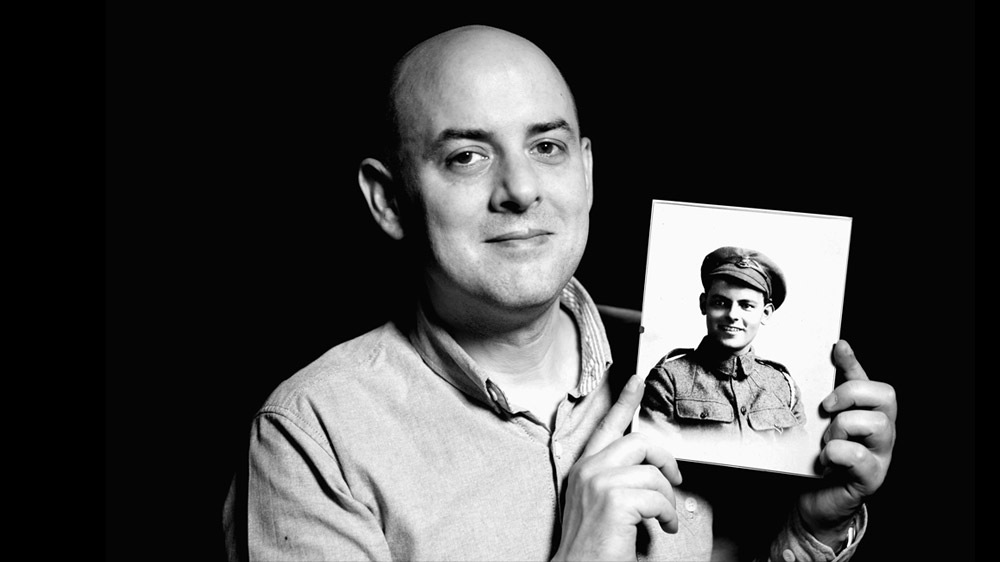

Albert Charles Todd

by

Tony Todd

Albert Charles Todd, my great uncle, was reported “missing, presumed dead” after his battalion went “over the top” at 7:30am on July 1, 1916, the bloody first day of the Battle of the Somme.

Albert, who lied about his age when he enlisted the year before, was just 18 when he was killed in what would be the most costly day in the history of the British Army.

From the English seaside town of Hastings, Albert was a Rifleman in the 12th Battalion (The Rangers) of the London Regiment.

Their objective on July 1, 1916 was Gommecourt, a heavily fortified German-held village at the far northern flank of the Somme battlefront.

It was a diversionary attack designed to keep pressure off the main assault further south. Most of the men in Albert’s battalion failed to reach their objectives, and those that did were pushed back by determined German defenders.

Albert Charles Todd died during the Battle of the Somme. He was 18 years old.

The battalion lost two-thirds of its strength on July 1, and Albert was one of the men who didn’t answer his name at roll-call that evening.

He was one of the 75,000 men whose bodies were never recovered in a battle that would rage from July through to November 1916 in a failed bid to break the stalemate of the Western Front.

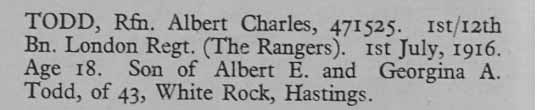

Albert has no grave. His name is inscribed at the vast Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme.

Albert’s death was a devastating loss for his parents, his sister and his younger brother Bill, my grandfather, who would feel the pain of loss all his life.

Bill’s sons – my father and my uncle – grew up acutely conscious of this family tragedy. This awareness remains strong in the third (and fourth) generation of our family.

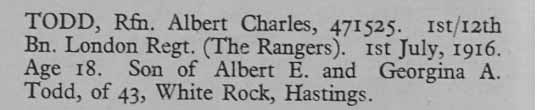

This register shows that Albert Charles Todd’s name is among those inscribed

in the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme.

We will be at Hébuterne, a tiny village just to the west of Gommecourt, on July 1, 2016, to make the short walk from the old trench line – identified thanks to maps from the period and a little help from the Internet – to the Gommecourt British Cemetery No. 2, a few hundred metres to the east, which marks the approximate limit of the 12th Battalion’s advance exactly 100 years before.

« He was one of the 75,000 men whose bodies were never recovered in a battle that would rage from July through to November 1916 in a failed bid to break the stalemate of the Western Front. »

I have been at FRANCE 24 since the very beginning, and I often drive back to the UK to see friends and family. The trip is always a happy one. Outbound – looking forward to seeing loved ones, the return – looking forward to getting back to what is now my home, France.

En route I pass by the Somme, the Bay of the Somme to be precise. I am always moved by the beauty of the landscape, summer or winter alike. But I can’t be there and not think of the men who died in battle.

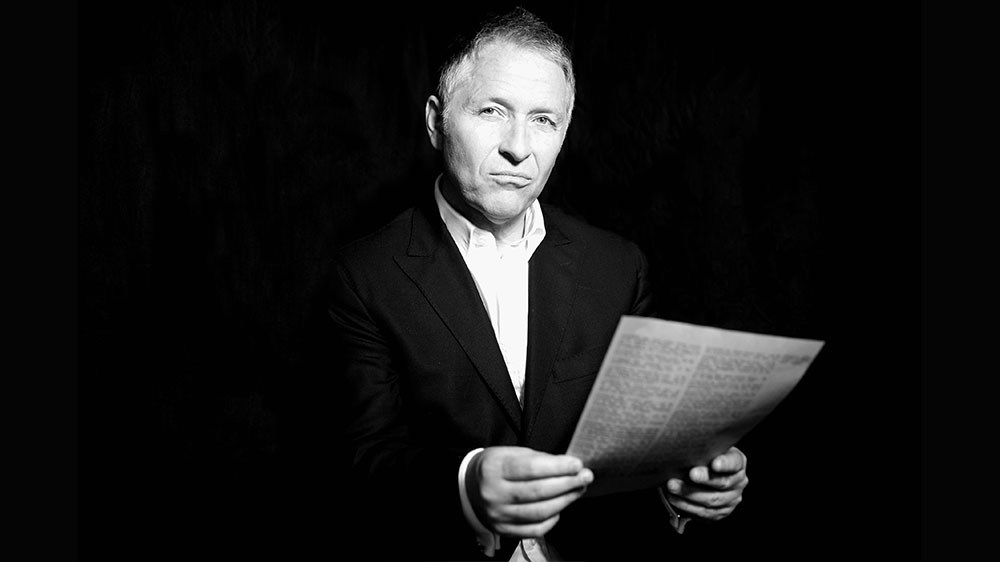

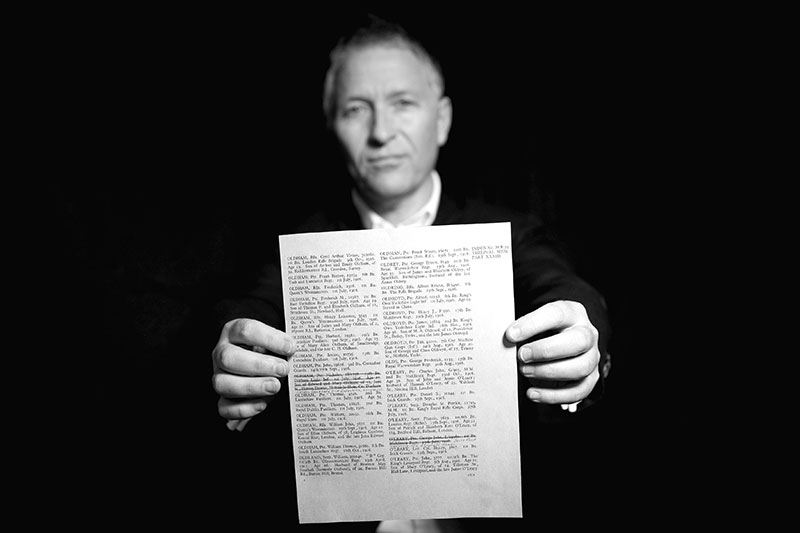

My great uncle was John O’Leary. He died on Saturday, August 5, 1916 at the Somme.

That day, there were no beautiful fields where birds make their nests. Just a battlefield. A killing field. John was 21. A conscript. He was in the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment 1st/9th battalion. His rank – the lowest – private. His number: 3777. These details are on the report we obtained from the British authorities. The telegram that arrived at his mother’s home in 1916 would scarcely have contained more. My grandmother only spoke to me about her brother once. She told me of a young man, handsome and funny. I can still see how her face was suddenly invaded by sadness. My grandmother was a smiling happy woman, except the day she told me about her brother.

The badge of the King's Regiment of Liverpool, to which John O'Leary belonged,

featured a prancing white horse. © North East Medals

It was a short conversation. She stopped talking, tears in her eyes. I would have been 7 or 8 years old. Only recently I found out the details about John O’Leary. The war (1st or 2nd) wasn’t talked about in our house when I was young. That said, the men of our family were very much involved, notably my grandfather and his seven brothers; they hold a record for the largest number of brothers in the military in a world war. The women didn’t shirk either – my grandmother worked in a munitions factory making bombs!

John O'Leary's name is engraved on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme.

John O’Leary was in the local regiment. The streets of Liverpool, from the Sacred Heart Church, to the length of Scotland Road, right down to the docks, every street knew about death. Husbands, sons, brothers, off to France to fight, never to return. Whenever I break my journey home at the Bay of the Somme I am moved by the beauty of the landscape, and by the spirits of the men who fell during the war. I think of my grandmother, and of her brother John O’Leary.

« I can still see how her face was suddenly invaded by sadness. My grandmother was a smiling happy woman, except the day she told me about her brother. »

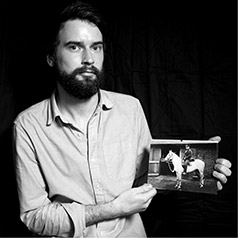

John Young

by

Annette Young

Born in 1893, my grandfather, John Young, had just finished his apprenticeship as a joiner working at my great-grandfather's firm in Cheshire in north-western England. In 1915, at the age of 22, he was called up to join the Royal Engineers and ended up on the Somme as a sapper (combat engineer). My father would say that as a boy, he tried many a time to get stories from him about his experiences on the front, but my grandfather refused to talk. Much later on, as we became familiar with the concept of post-traumatic stress disorder, our family realised he must have been suffering enormously from PTSD.

My grandfather very rarely, if at all, spoke of his time in the trenches. The only stories my father was told were about how the sappers would be sent out at night in groups of 15 into no-man's land to lay mines, booby traps and barbed wire. On one terrible night, only eight came back.

The badge of the Corps of Royal Engineers, John Young's corps.

They were often given the task of cleaning all the military equipment that had been retrieved from the battlefields. One time, in the trenches, my grandfather was cleaning a hand grenade and the safety clip broke off, as it had become rusty. Realising what had happened, he attempted to throw it up into the air but it blew up in his hand and splattered him with metal. It also killed three of his comrades standing right behind him. Despite shards of metal slicing his flesh, it miraculously missed the main arteries.

He was immediately taken to a field hospital and when he recovered consciousness, the staff were amazed he was still alive. As he came to, one of the nurses told him about his three comrades, which my father said was far from a wise move – as that sent my grandfather into deep shock. He blamed himself entirely for the loss of the three other young men and never recovered emotionally. Yet at that time, nobody had any clue about psychological trauma and the dangers it posed.

My grandfather was sent to Aberdeen in Scotland where a surgeon managed to save his arm. That was the time the accompanying photograph was taken – as he recuperated from surgery. When I look at it, I'm filled with sadness. A young man who witnessed the ugliest of human nature, all before his 23rd birthday.

John Young's family kept this picture of his wartime convalescence in a hospital in Aberdeen, Scotland.

After recovery, thanks to his injuries, my grandfather found he had lost his trainee position. He became a commercial traveller before successfully setting up his own building firm in Macclesfield. He met my grandmother one year after the war ended and eventually married. A decade later, they had my father.

Dad went on to become an architect, much to my grandfather's sadness since under the law at that time, an architect could not own or have any financial interest in a building firm. It was deemed a conflict of interest. It also meant my grandfather's firm would not be kept within the family, something that caused him great sadness.

But with the benefit of hindsight, my father realised that my grandfather had suffered periods of immense depression – no doubt caused by his war experiences. In fact, when he was 62, despite being a new grandfather, a highly successful businessman and well-loved by many, he took his own life. According to my father, there were no warning signals. But this was England in the 1950s, not like now where soldiers returning from a war zone undergo close scrutiny for emotional trauma.

In fact, I was not told of his suicide until I was in my 20s; I now realise how painful it was for my father to retell the story. How he too, somehow, felt responsible for his father's death; for not realising the depth of emotional pain that his own father was suffering.

And proving, once again, how the horrors of war are passed on from one generation to another, decades after the last bullet or tank shell has been fired.

** In memory of my father, Gordon Young, who passed away on March 7, 2016

« He blamed himself entirely for the loss of the three other young men and never recovered emotionally. Yet at that time, nobody had any clue about psychological trauma and the dangers it posed. »

George Samuel Tate, my great grandfather, was 18 when he joined the British army in 1911. No one I’ve spoken to in my family is really sure what prompted him to go into the military. He was one of 14 children, growing up in a working-class neighbourhood of Islington in north London. Before the army he worked as a porter on the railways – probably not a very lucrative career – so there’s a good chance he joined up just to earn a better wage, or a degree of independence away from the family home.

He joined the 19th London Regiment as a private and was dispatched to Le Havre, France, in March of 1915. He made it all the way through the war, ending up with the rank of sergeant.

No one knows that much about what he did in the First World War – apparently he didn’t like to talk about it much. Most of what I do know comes from official records. For example, I know that at the Somme his regiment fought in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, the first time tanks were ever used in battle, which must have been a pretty incredible sight for men of his generation.

But much of what he did personally during the war, what his day to day life was like and the mark it left on him, remains more or less a complete mystery. I think like lots of men of his generation, he preferred to leave it in the past.

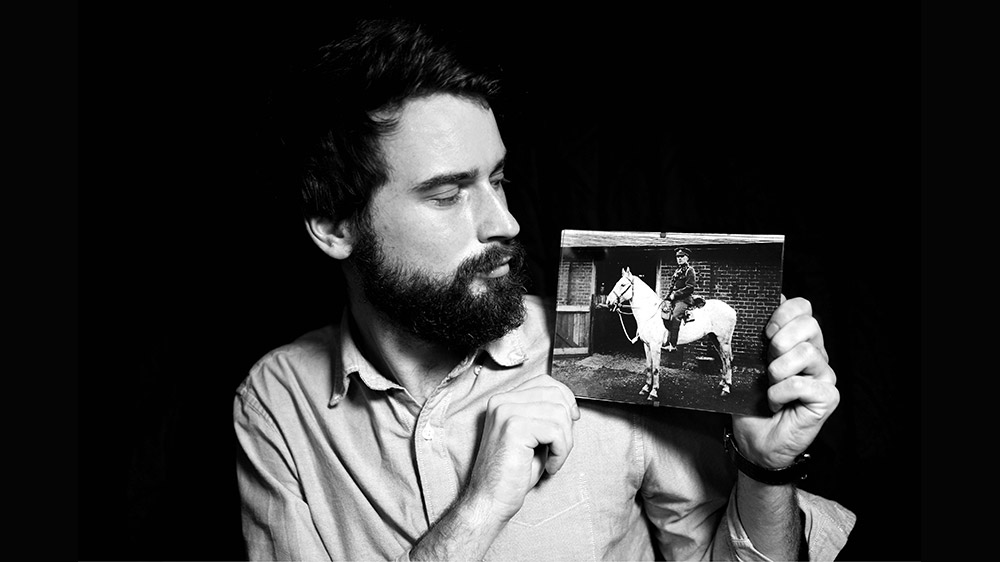

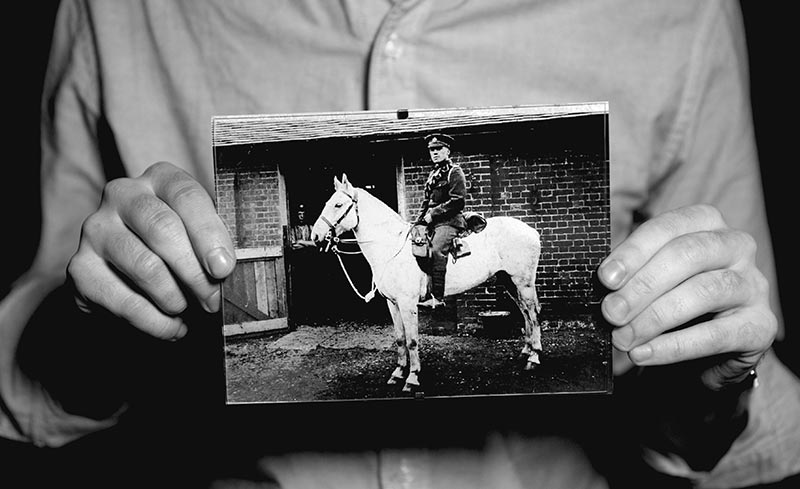

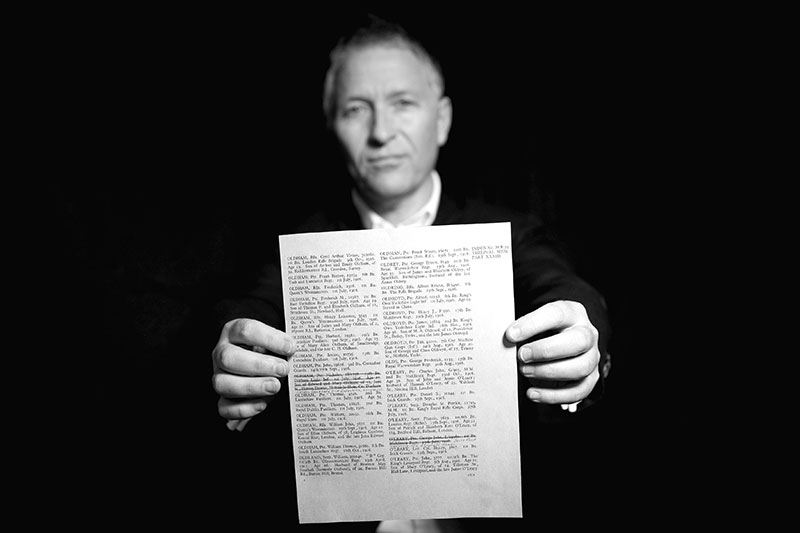

George Samuel Tate kept a photograph of his horse Betsy, killed on the battlefield, his entire life.

There are a couple of things I do know about his war years, though. I know that he had the honour of being mentioned in dispatches for going into a bombing raid to retrieve the body of a high-ranking officer who had been killed. And I know that during the war he rode a horse named Betsy, who was shot out from under him during a battle. He was so fond of her that after her death, in a rather macabre fashion, he had her hoof mounted and kept it on the mantelpiece back in England along with her photo until his death in 1975.

After the war he went back to working on the railways in London and in 1921 married Mary Ann Edwards, my great grandmother.

Samuel Ball’s family also found this photograph, apparently taken before the war. George Samuel Tate is the second soldier from the right.

To be honest, I had a vague awareness that some of my relatives had fought in the First World War but until I researched it didn't really know much about it. I guess that's partly to do with George himself and a willingness to move on with life after getting back home. But as that era slips ever further into the past, I think finding ways to remember it becomes ever more important. George and I share little beyond genetics – our lives could hardly be more different – but knowing that someone I'm related to lived through that makes it seem more real, more personal. Most of all, I'm just glad he was one of the lucky ones who survived, otherwise I wouldn't be here.

« Much of what he did personally during the war, what his day to day life was like and the mark it left on him, remains more or less a complete mystery. I think like lots of men of his generation, he preferred to leave it in the past. »

Jean Jutel

and Pierre Passelande

by

Stéphanie Trouillard

I visited the Thiepval Memorial for the Missing of the Somme on July 1, 2015, for the annual ceremony that marked 99 years to the day since the bloody opening of the murderous 1916 battle. Although I was in my native France, I had the strong feeling that day that I was on British soil. Everyone there was British, proudly wearing poppies – the British symbol of remembrance for wartime sacrifice – on their lapels.

Indeed, The Somme is etched deeply into the British collective memory. Here, on land where so many of their ancestors fell, these visitors from England, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and from all corners of a globe once dominated by the British Empire, all feel somehow at home. But it wasn’t just the British who were involved in this battle. At school, we were taught about the horror of Verdun and the Chemin des Dames battles that raged further south on the Western Front.

Reading further on the Battle of the Somme, I became aware of the extent that this was not just a British operation, and that there was significant French involvement too. Thousands of French “Poilus” (the nickname for French soldiers, which means “hairy ones”) fought alongside the British “Tommies”. Some 200,000 Frenchmen were killed over the five months that the Battle of the Somme raged.

Stéphanie Trouillard chose two toy soldiers to represent her great-great-uncles: an artilleryman and an infantry soldier from the French army.

I decided to check if any of my family members had been involved. On my mother’s side, my ancestors were living in the Malestroit area of Brittany. One great-great-grandfather, Joseph Jutel, was not called up because he suffered from severe asthma. His brother Jean, however, was enlisted. Born in 1889, he was mobilised at the very beginning of the war, in 1914, as part of the 10th Artillery Regiment then based in Rennes. Jean the farmer became Gunner Jutel, and fought at the Battle of the Marne, then at Artois and the Argonne.

His regiment was withdrawn from the line and sent to the Somme in 1916. After weeks of training and preparation, the 10th Artillery Regiment participated in the September 1916 attack on the villages of Chilly and Chaulnes, “a brilliant success with all objectives taken, but with a high number of casualties”, according to the regiment’s official military history. Jean made it through the battle without injury. He was hospitalised after breathing poison gas at Verdun the following year, then rejoined his regiment and served till the end of the conflict. He returned to his village, Caro, in Brittany in July 1919.

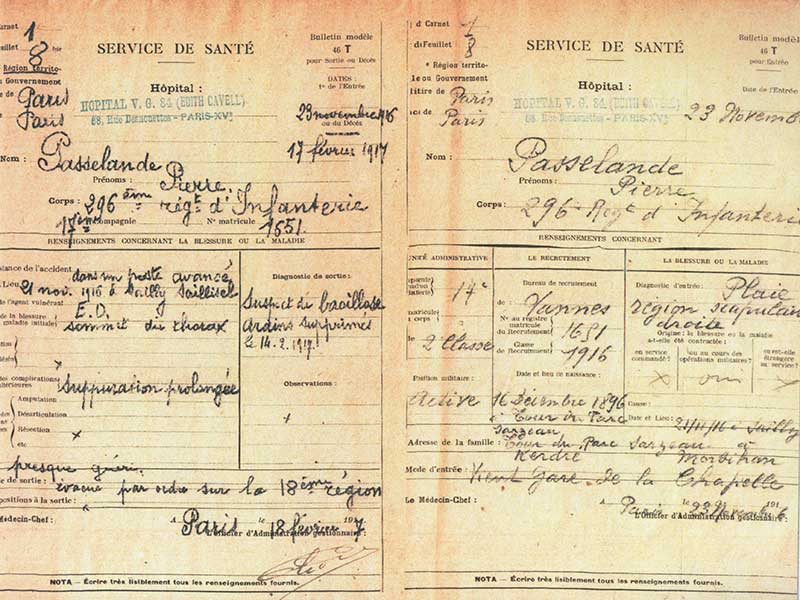

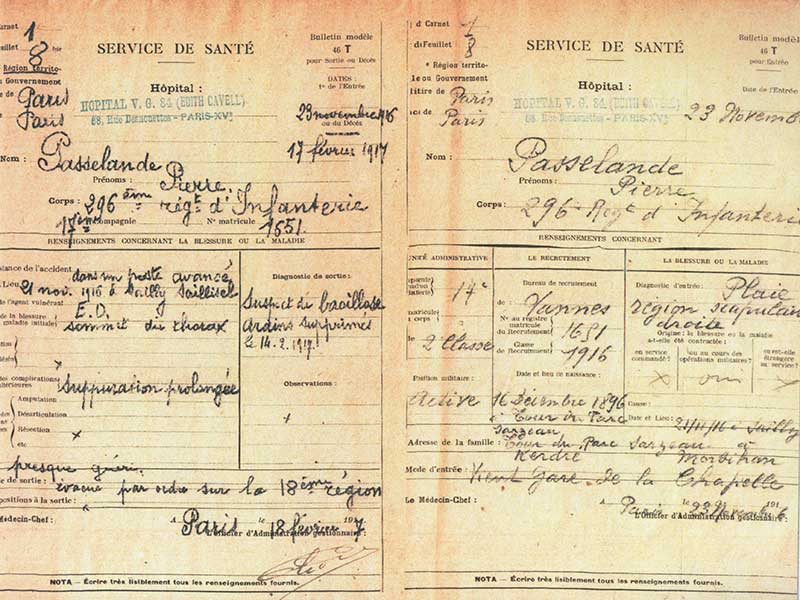

I discovered that, on my father’s side, another great-great-uncle also participated in the Somme battle. Pierre Passelande, also from a farming family and also from Brittany, was 18 when war was declared in August 1914. He was called up in April 1915, but it would be another year before he reached the front with the 296th Infantry Regiment at the Somme, where he fought alongside the British against a German position at Combles.

He was injured in the shoulder a month later by a shell explosion, and would spend a year in hospital recovering, before going back to the front with the 68th Infantry Regiment. He would serve them with distinction, winning the Croix de Guerre medal with a bronze star and the Military Medal. He was demobilised in 1919, having reached the rank of Corporal, and went on to become a customs officer.

This document was kept in the army hospital archives. It was filled out on November 23, 1916, and describes Pierre Passelande’s injuries upon his arrival in a Paris hospital.

Sadly, I have no pictures of either of my great-great uncles. A century after their participation in the war, they were all but forgotten by the family. I was shocked to discover, by putting the pieces of the puzzle together, that they had participated in some of the war’s biggest battles: the Marne, Verdun, Champagne and now the Somme.

Just a few months ago, I’d still believed that I had only one ancestor who had fought. But by piecing together my family tree, it turns out that I have dozens of ancestors who were in uniform from 1914 to 1919. I can’t but think of the suffering on the battlefields, as well as the agony of their families, waiting and hoping for their return to Brittany. I hope that in recounting this I have resurrected their memory, and also provided a reminder that French soldiers also took part in the Battle of the Somme.

« Just a few months ago, I’d still believed that I had only one ancestor who had fought. But by piecing together my family tree, it turns out that I actually have dozens of ancestors who were in uniform from 1914 to 1919. »