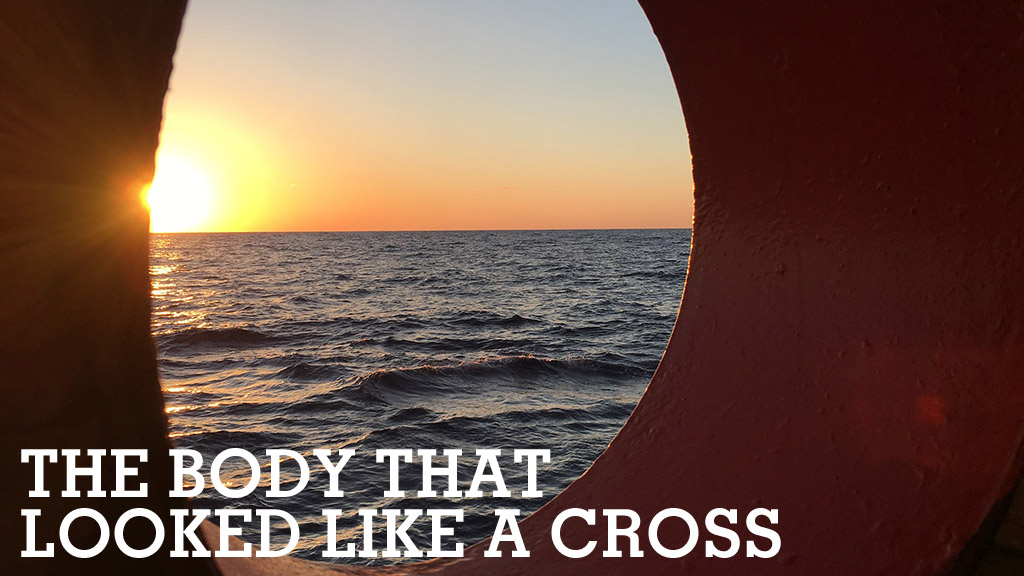

For more than a year, the Aquarius – a former fishing boat – has been cruising the Libyan coast searching for the thousands of migrants who attempt the crossing to Italy every day. Our reporter spent 10 days on board with the humanitarian workers who are on the front line of rescue operations.

The Aquarius left port with 30 people on board; now it has 217. At night, the aft deck becomes its own sea of polar blankets that obscure the bodies beneath. In winter, when the migrants accumulate layer after layer, the spring air and a night sky strewn with stars that glare in the absence of light pollution are two small points of consolation. Except nobody is looking at the sky. After weeks of exile and the challenge of the sea, almost all of the 187 rescued migrants are fast asleep. Silence reigns over the Aquarius.

The next day the sea is frothy and agitated. We walk between bodies stretched out on the deck, weaving our steps through sleeping legs as the ship tosses and bobs. Some of the migrants are sitting upright, perfectly silent.

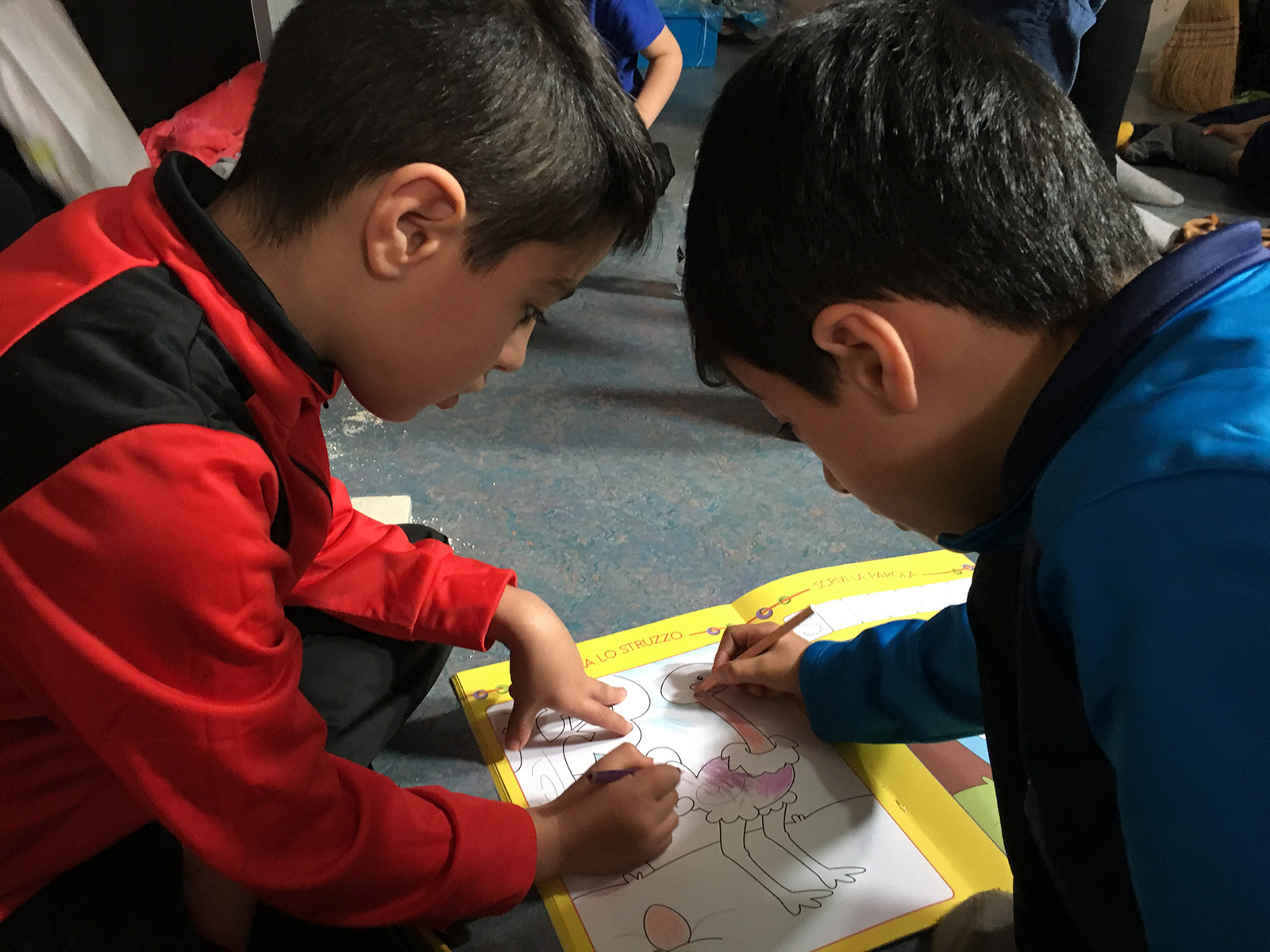

In the “shelter,” the women are resting, too, though children’s cries ricochet off the walls. A Syrian woman is lying down on a blanket, exhausted from her journey, too tired to deal with her screaming daughter. Instead, Elizabeth, the midwife, is trying to calm her down. To distract the littlest ones, we bring out colouring books and Lego. In less than 24 hours, the room has become a hectic shambles of a place. It smells of urine mixed with baby lotion.

A mother tries to explain that her son wants a pacifier, and that another is seasick and can barely stand up. Elizabeth is on it: she boils water to mix with powdered milk, gives shots of anti-nausea meds, and helps Connor, the MSF doctor, in the clinic. The women rarely leave the shelter, except to go to the bathrooms on the rear deck. They don’t want to see the Mediterranean. “I don’t like it,” says a teenage Syrian girl, gesturing with her finger towards the sea.

Two days to show them that not everyone’s a bastard.

As ten o’clock nears, lunch distribution starts. It’s almost funny to see the 187 migrants dressed nearly identically, in blue sweatpants and hats, the clothes that were handed out as part of the kits. At mealtimes, the ritual is always the same. The migrants rinse their hands, and grab cups of tea—always with unimaginable amounts of sugar—and a piece of bread. The crew mark their bracelets with the stroke of a pen, to keep track of who has already been served, and who hasn’t. Nobody complains about the repetitiveness of the meals. No one grumbles about the long line. The silence is surprising.

Maybe that’s why music is played during meal distribution, to lighten the atmosphere. This morning, Tanguy has brought his computer, which is pumping out Bob Marley. “Gotta play something not too depressing, but not something too energetic and happy either,” he says, “it’s about finding a balance.” The Jamaican reggae icon is a hit with Sarowar, a 17-year-old from Bangladesh, as well as with Kissima, 25, from Gambia, who is sitting just a few centimetres from the speakers. “It’s been so long since I’ve heard music,” he says with a fascinated smile.

The teams from SOS Méditerranée and MSF have two days to “refurbish” the migrants before reaching Italy. Two days to teach them to believe again that “not everyone’s a bastard”. This is the last place where nothing will be asked of them. This trip is free. “It’s important that they feel protected, even if it’s just for a few hours,” says Marcella, MSF’s mission chief. “It’s important to give them back their dignity.” Some of the team members are more natural than others when it comes to interacting with the migrants, more at ease reaching out, talking, touching hands. Bene stays back a bit. “I keep a bit of distance, I know,” she says, watching them head to the back of the ship for their last night on board. “But I just don’t know if I can do any more than I already am… and I’m afraid of being awkward, of seeming fake.”

On the last day on the ship, everyone gathers on the bridge, faces turned towards the horizon, despite weather that has turned sour, the rising swell, the rolling of the deck. “Will we soon be in Italy?” asks Albara, for the tenth time at least. Yes, Italy is close. Just four or five hours away. At this stage, few of the humanitarian volunteers talk about what will happen when everyone disembarks. “Because you never know what will happen,” Natalia, a communications officer for SOS Méditerranée, explains. Except that we more or less do know what will happen. The majority of the migrants will not get asylum, many will almost certainly be sent back to their countries of origin. But how do you tell them that, when all of them begin to smile at the first glimpse of the Italian coast?

It’s early evening when the Aquarius docks at Pozzallo, in the south of Sicily. The Red Cross is waiting in the port, along with a few police officers and health authorities who will board to inspect the passengers one by one. Seeing the crowd of people waiting on land, Albara begins to panic a little bit. It’s the first time since the rescue that he has been agitated. “Why are there police?” he keeps asking, gripping my arm. He seems to have forgotten everything that MSF and SOS Méditerranée have explained about the process that awaits them.

It takes two hours for the 187 migrants to make it off the ship, and to disappear from the dock. Albara marches prudently down the bridge to shore, trailing behind his friend Issam. Two guards from Frontex approach him, grasp his hand in a friendly way, and reassure him. They offer him a juice box and sandals, so that he doesn’t have to walk to the processing centre in town wearing only socks. He turns back towards me and smiles. Once in the bus, the Sudanese adolescent becomes one more statistic. On the Aquarius, he was a travel companion, on the docks of the Pozzallo port, he’s just another migrant.

When evening falls, the boat is empty at last, but the rescue teams barely have a moment of respite. The boat has to be cleaned, the bathrooms washed down, the trash emptied. Everything made shipshape for the next group. Bene, Mary, Max, Anthony, Reem, Iasonas, Nicholas, Elizabeth, and all the others will haul anchor and leave again for the SAR zone this very night, after throwing down a few quick beers on the quays. They don’t yet know that a few days later, they will come to the aid of 732 people off the coast of Libya, three times more than the trip that just ended.

They will once again stretch out their arms, put the same Zodiacs in the water, and repeat the same rescues. “Because life has to conquer the sea,” Elizabeth had said to me a few days earlier. And for that to happen, the living must no longer sink beneath the waves.